Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

HANOVER — Dartmouth President Sian Beilock and college administrators faced pointed criticism at a meeting with faculty on Monday regarding the arrest of 89 students, staff, faculty and community members by police in riot gear at a protest on the...

Local Roundup: Hartford tops Woodstock in close girls lacrosse contest

Editor’s note: To have your team’s results included in the Local Roundup, visit https://www.vnews.com/submit-a-score.Girls Lacrosse Hartford 11, Woodstock 7 Key players: Hartford — Audrey Rupp (six goals, one assist), Madi Barwood (three goals), Nella...

Most Read

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Hartford Selectboard considers banner policy amid controversy over ‘Hometown Heroes’ project

Hartford Selectboard considers banner policy amid controversy over ‘Hometown Heroes’ project

Killington is the East’s largest ski resort. A developer wants to expand on that in a big way.

Killington is the East’s largest ski resort. A developer wants to expand on that in a big way.

Editors Picks

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Sports

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — The pass was perfect, a classic backdoor feed that arced from Paisley Danaher to Madison Barwood and resulted in the winning goal Saturday for the undefeated Hartford High girls lacrosse team.The strike lifted the host...

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

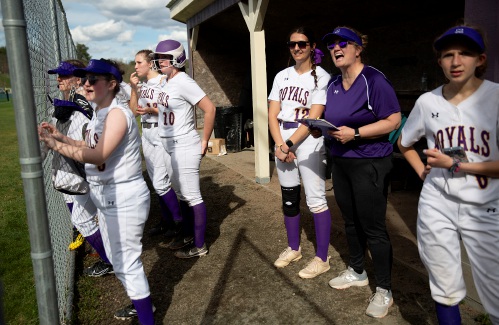

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Opinion

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s conversion from “Never Trump” to “Ever Trump” occurred not on the road to Damascus but on the Republican Party’s road to perdition.On ABC News last Sunday, Sununu affirmed his intention to support Donald Trump for...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

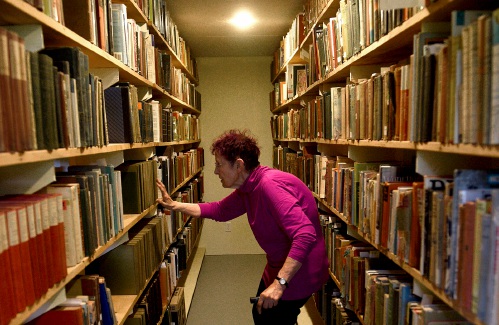

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Pampered pup

Eyes and ears

Eyes and ears

Afternoon outing in Norwich

Afternoon outing in Norwich

In the garden

In the garden

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Arts & Life

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Before franchised fast food and corporate-owned restaurants hit the Upper Valley, there was a time when locally owned diners and a variety of family-run eating establishments flourished and produced many fond memories and much nostalgia. For at least...

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Obituaries

Barbara W. Bascetta

Barbara W. Bascetta

Jupiter, FL - With saddened hearts and joyous memories, we share the passing of Barbara Whitcomb Bascetta on April 29, 2024. She passed peacefully in Jupiter, Florida surrounded by her loving family. Barbara is survived by her husband, ... remainder of obit for Barbara W. Bascetta

Kelly F. Kangas

Kelly F. Kangas

Hartford, VT - Our sunshine, Kelly Flora (Bagley) Kangas left this world far too early on Thursday, April 25th from complications of an illness at the Jack Byrne Center. Kelly entered this world the last of four children on September 6,... remainder of obit for Kelly F. Kangas

Robert H. Mattson

Robert H. Mattson

Hartford, VT - Robert H. Mattson, age 76, passed Wednesday, February 28, 2024. A graveside committal service will be held at 1pm on Friday, May 10th, 2024 in the Ascutney Cemetery in Windsor, VT. Knight Funeral Home has been entrust... remainder of obit for Robert H. Mattson

Joan Van Hook Harris

Joan Van Hook Harris

Littleton, CO - Joan Van Hook Harris, longtime resident of New London, New Hampshire, died peacefully at her assisted living home in Littleton Colorado on April 17, 2024 surrounded by her family. She was 93 years old. Born on May 23, 19... remainder of obit for Joan Van Hook Harris

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

After reaching agreement with Middlebury College, student protesters take down encampment

After reaching agreement with Middlebury College, student protesters take down encampment

UNH faculty and students call on university police chief to resign following his alleged assault on a student

UNH faculty and students call on university police chief to resign following his alleged assault on a student

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community  Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties

Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties