Latest News

Four vying for one seat on Newport Selectboard

Four vying for one seat on Newport Selectboard

Plan on track to ship Upper Valley mail to Connecticut for sorting

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — The U.S. Postal Service will proceed with a plan to move mail sorting operations for Upper Valley communities from White River Junction to Connecticut, according to a USPS facilities study released this week.The plan is...

Judge won’t reconvene jury after disputed verdict in New Hampshire youth center abuse case

CONCORD — The judge who oversaw a landmark trial over abuse at New Hampshire’s youth detention center won’t reconvene the jury but says he will consider other options to address the disputed $38 million verdict.David Meehan, who alleged he was...

Most Read

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school

Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school

Editors Picks

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Sports

Young Oxbow baseball team struggles, but coach still finds joy in teaching the game

BRADFORD, Vt. — Oxbow High’s baseball scoreboard remained aglow half an hour after Tuesday’s game with U-32. Not that the Olympians needed a lengthy reminder of the loss or its 22-6 denouement.Oxbow is 1-6 and has been outscored 91-36 this season....

Local Roundup: Hartford tops Woodstock in close girls lacrosse contest

Local Roundup: Hartford tops Woodstock in close girls lacrosse contest

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Opinion

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s conversion from “Never Trump” to “Ever Trump” occurred not on the road to Damascus but on the Republican Party’s road to perdition.On ABC News last Sunday, Sununu affirmed his intention to support Donald Trump for...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

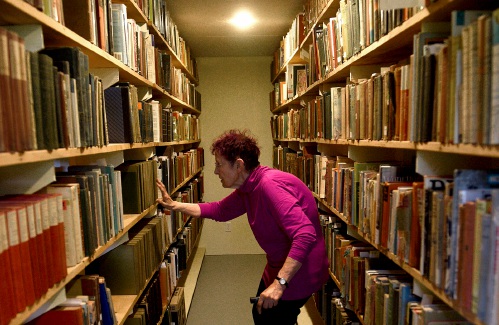

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Spring in the garden

Deposit with interest

Deposit with interest

Scoping things out

Scoping things out

Pampered pup

Pampered pup

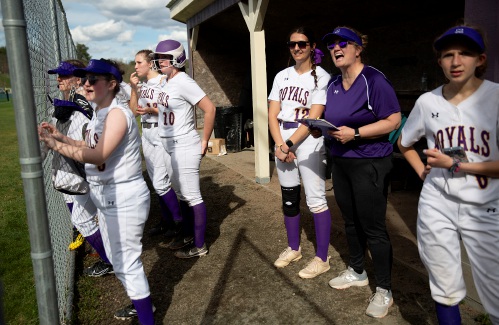

Eyes and ears

Eyes and ears

Arts & Life

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together

CANAAN — A few summers ago, during the pandemic, Martin Decato and Peter Dionne got together to play music. Decato is a longtime pro, Dionne an avid amateur.They looked around for a good place to make music videos, and didn’t have to look far. They...

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Obituaries

Derek Lamson Siegler

Derek Lamson Siegler

Hinesburg, VT - Derek Lamson Siegler, a devoted son, husband, father and friend passed away suddenly on April 29, 2024 from heart failure. He was a kind, compassionate person, who expressed his feelings in his music, art and writing. H... remainder of obit for Derek Lamson Siegler

Barbara Crowe

Barbara Crowe

Enfield, NH - Barbara Crowe passed away on April 29th, 2024 at Maple Ridge Memory Care in Essex Junction, Vermont at the age of 86. She was surrounded by many who loved her dearly. Barb was a dedicated wife, mother, grandmother, and a ... remainder of obit for Barbara Crowe

Roberta M. Haley

Roberta M. Haley

Wilder, VT - Roberta M. Haley, age 77, passed Tuesday, May 7, 2024. A full obituary will be published in an upcoming edition of the Valley News. Knight Funeral Home in White River Junction, VT has been entrusted with arrangements. ... remainder of obit for Roberta M. Haley

Barbara Mae Sprague

Barbara Mae Sprague

Lyme, NH - Barbara Mae Sprague (Hood), age 92, passed Tuesday, November 7, 2023. A graveside service for Barbara will be held on June 4th at 11 am at the Highland Cemetery (on High Street in Lyme, NH). Friends and family are welcome... remainder of obit for Barbara Mae Sprague

Lebanon’s Jewell back from auto accident, more aware of ‘drowsy driving’ dangers

Lebanon’s Jewell back from auto accident, more aware of ‘drowsy driving’ dangers

New Hampshire man sentenced to minimum 56 years on murder, other charges in young daughter’s death

New Hampshire man sentenced to minimum 56 years on murder, other charges in young daughter’s death

Over Easy: On bread, buttered popcorn and big sandwiches

Over Easy: On bread, buttered popcorn and big sandwiches

Trucker acquitted in deadly crash asks for license back, but state says he contributed to accident

Trucker acquitted in deadly crash asks for license back, but state says he contributed to accident

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community