Latest News

Volunteers work to repair Upper Valley trails damaged by storms

WOODSTOCK — The Ottauquechee River Trail averaged around 500 visitors a week during peak months until last July’s flooding, which left behind debris along the trail, which begins at East End Park off Route 4.The roughly 3-mile trail in downtown...

Big drop in tuition and aid is boosting Colby-Sawyer

One year after it made a radical change to how it charges students by slashing both tuition and financial aid, Colby-Sawyer College’s president says the benefits seem to be outweighing the risks, indirectly helped this year by problems with the...

Most Read

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

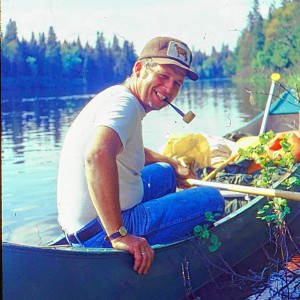

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

Editors Picks

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Sports

Local Roundup: Thetford shuts out Windsor in baseball no-hitter

Editor’s note: To have your team’s results included in the Local Roundup, visit https://www.vnews.com/submit-a-score.Baseball Thetford 21, Windsor 0 Highlights: Thetford’s Xander Oshoniyi, Owen Goordrich, Liam Brooks and Dempsey McGovern combined for...

Bears ride strong 2nd half to win in girls lacrosse

Bears ride strong 2nd half to win in girls lacrosse

Woodstock boys lax defense steps up, holds off Hartford

Woodstock boys lax defense steps up, holds off Hartford

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Opinion

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Hey, Major League Baseball, does the name Pete Rose ring a bell? Remember him, “Charlie Hustle”? One of the game’s greatest players, whom you banned for life in 1989 because he bet on baseball games?We ask because you have on your hands another...

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

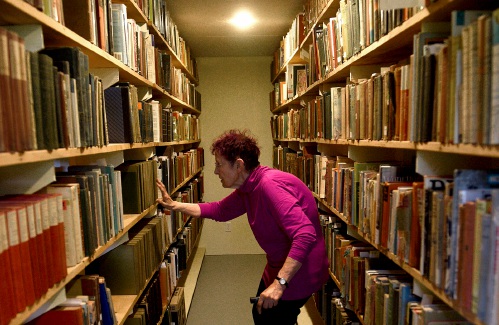

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

Photos

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Drawn to dragons

Drawn to dragons

Clear and free in Hartford

Clear and free in Hartford

Ramping up their foraging

Ramping up their foraging

Roadside assist in Bethel

Roadside assist in Bethel

Arts & Life

Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties

NEWPORT — When Kate Luppold put out the call for submissions for the Library Arts Center’s exhibition, she expected artists would take its theme of “home” literally.“I expected a lot of houses with white picket fences,” Luppold, the Newport-based...

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Obituaries

Gail J. Farrar

Gail J. Farrar

Ascutney, VT - Gail J. Farrar, age 96, passed Tuesday, February 6, 2024. A graveside service will be held in the Cavendish Village Cemetery at 2pm on Saturday, May 4, 2024. Knight Funeral Home in Windsor, VT has been entrusted with ... remainder of obit for Gail J. Farrar

Cynthia Beam

Cynthia Beam

North Haverill, NH - Cynthia J. Beam of North Haverhill, NH passed away at the age of 68, on April 13, 2024. Cynthia was born on May 20, 1955 in Lawrence MA to John and Marguerite (Hallock) Beam. Names she was known for were CJ, Cyndi, ... remainder of obit for Cynthia Beam

Philip Porter

Philip Porter

Hanover, NH - Philip Wayland Porter died on Wednesday, April 24th, 2024. He was born July 9, 1928, in Hanover, NH, the son of Wayland R. and Bertha (La Plante) Porter. Philip married Patricia Elizabeth Garrigus on September 5, 1950, in ... remainder of obit for Philip Porter

Michael S. Thurston

Michael S. Thurston

West Lebanon, NH - Michael S. Thurston, age 60, died Friday, April 26, 2024. A full obituary will be published in an upcoming edition of the Valley News. The Rand-Wilson Funeral Home in Hanover, NH is assisting the family. ... remainder of obit for Michael S. Thurston

How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war

How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price