Homeless Upper Valley couple faces ‘a very tough situation’

SHARON — With homelessness at record levels in Vermont, an Upper Valley couple’s precarious living situation toppled last month following a trespassing order from the state and complaints from nearby residents.In late March, the couple hired a tow...

Kenyon: Constitutional rights should trump Dartmouth’s private interests

Andrew Tefft wasn’t inside a tent on the Dartmouth College Green. He hadn’t locked arms with protesters who had formed a circle around the short-lived encampment. The 45-year-old Hanover native didn’t have a pro-Palestinian sign.Still within 30...

Most Read

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

West Lebanon crash

West Lebanon crash

Plan on track to ship Upper Valley mail to Connecticut for sorting

Plan on track to ship Upper Valley mail to Connecticut for sorting

Lebanon’s Jewell back from auto accident, more aware of ‘drowsy driving’ dangers

Lebanon’s Jewell back from auto accident, more aware of ‘drowsy driving’ dangers

Longtime employees buy West Lebanon pizzeria

Longtime employees buy West Lebanon pizzeria

Editors Picks

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Sports

Young Oxbow baseball team struggles, but coach still finds joy in teaching the game

BRADFORD, Vt. — Oxbow High’s baseball scoreboard remained aglow half an hour after Tuesday’s game with U-32. Not that the Olympians needed a lengthy reminder of the loss or its 22-6 denouement.Oxbow is 1-6 and has been outscored 91-36 this season....

Local Roundup: Hartford tops Woodstock in close girls lacrosse contest

Local Roundup: Hartford tops Woodstock in close girls lacrosse contest

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Opinion

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s conversion from “Never Trump” to “Ever Trump” occurred not on the road to Damascus but on the Republican Party’s road to perdition.On ABC News last Sunday, Sununu affirmed his intention to support Donald Trump for...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Spring in the garden

Deposit with interest

Deposit with interest

Scoping things out

Scoping things out

Pampered pup

Pampered pup

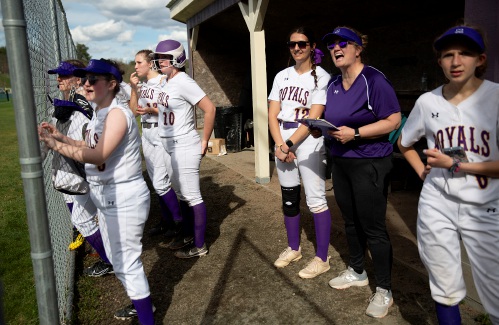

Eyes and ears

Eyes and ears

Arts & Life

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together

CANAAN — A few summers ago, during the pandemic, Martin Decato and Peter Dionne got together to play music. Decato is a longtime pro, Dionne an avid amateur.They looked around for a good place to make music videos, and didn’t have to look far. They...

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Obituaries

Sandra A. Smith

Sandra A. Smith

Ascutney, VT - Sandra A. Smith, age 79, passed Friday, February 2, 2024. Visitation will begin at 10am Knight Funeral Home in White River Jct., VT on Friday, May 17, 2024, until the time of service at 12pm. Burial will follow in the... remainder of obit for Sandra A. Smith

Jane Quale

Jane Quale

Hanover, NH - Jane Quale passed away peacefully on December 19, 2024 at home. Born on November 24, 1938 in Grand Forks ND, she graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1960 earning Phi Beta Kappa honors and serving as Homecoming Qu... remainder of obit for Jane Quale

Vernona S. Bell

Vernona S. Bell

White River Junction, VT - Vernona S. Bell, 83, died Saturday, May 4, 2024, at home with her family. She was born October 19, 1940, a daughter of Victor and Vernona (Heck) Wallace in the Bronx borough of New York City. Vernona attended... remainder of obit for Vernona S. Bell

Derek Lamson Siegler

Derek Lamson Siegler

Hinesburg, VT - Derek Lamson Siegler, a devoted son, husband, father and friend passed away suddenly on April 29, 2024 from heart failure. He was a kind, compassionate person, who expressed his feelings in his music, art and writing. H... remainder of obit for Derek Lamson Siegler

Crane crash on Interstate 89

Crane crash on Interstate 89

Local Roundup: Lebanon boys tennis blanks Kingswood

Local Roundup: Lebanon boys tennis blanks Kingswood

Four vying for one seat on Newport Selectboard

Four vying for one seat on Newport Selectboard

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community