Claremont movie theater to close at end of May

CLAREMONT — The ticket sales at a recent midweek matinee at Claremont Cinema 6 provided an indication why the theater is closing at the end of the month.The theater had five showtimes with seating of 150 to 225 for each and starting times between 4...

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Under the cover of darkness, 20 New Hampshire State Police storm troopers in full riot gear marched in a single row across the Dartmouth Green, where hundreds of pro-Palestinian protesters were peacefully chanting their opposition to the war in Gaza...

Most Read

Dartmouth moves swiftly to stymie demonstration, leads to 90 arrests

Dartmouth moves swiftly to stymie demonstration, leads to 90 arrests

Dartmouth graduate student-workers go on strike

Dartmouth graduate student-workers go on strike

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Art Notes: City Center Ballet celebrates 25 years

Art Notes: City Center Ballet celebrates 25 years

Editors Picks

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Sports

Local Roundup: Hartford players reach career marks in girls lacrosse

Editor’s note: To have your team’s results included in the Local Roundup, visit https://www.vnews.com/submit-a-score.Girls Lacrosse Hartford 13, Rice 8 Key players: Hartford — Audrey Rupp (5 goals, 1 assist); Madi Barwood (4 goals, 1 assist); Izzy...

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Local Roundup: Hanover, Lebanon girls tennis teams are undefeated

Local Roundup: Hanover, Lebanon girls tennis teams are undefeated

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Opinion

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s conversion from “Never Trump” to “Ever Trump” occurred not on the road to Damascus but on the Republican Party’s road to perdition.On ABC News last Sunday, Sununu affirmed his intention to support Donald Trump for...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

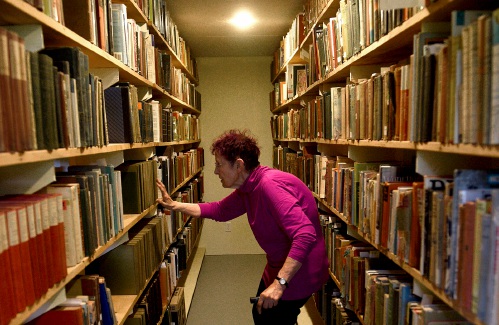

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

In the garden

Sandy Gourley, 76, walks her Lebanon yard, looking at the trees, rocks and sprouting spring flowers. Gourley said she looks forward to working on her landscaping projects, but some recent health problems have slowed her down. “This is what I like to...

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Drawn to dragons

Drawn to dragons

Clear and free in Hartford

Clear and free in Hartford

Ramping up their foraging

Ramping up their foraging

Arts & Life

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

After years of absence, the most patriotic bird in the sky returned to Vermont — but it might’ve come at another’s expense.Vermont finally took the bald eagle off of its endangered species list in 2022 following years of reintroduction efforts...

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

Obituaries

Robert H. Mattson

Robert H. Mattson

Hartford, VT - Robert H. Mattson, age 76, passed Wednesday, February 28, 2024. A graveside committal service will be held at 1pm on Friday, May 10th, 2024 in the Ascutney Cemetery in Windsor, VT. Knight Funeral Home has been entrust... remainder of obit for Robert H. Mattson

Mary Olive Tracy

Mary Olive Tracy

Windsor, VT - Mary Olive (Sulham) Tracy, 99, died Saturday, April 27, 2024, at the Stoughton House in Windsor, VT. She was born June 11, 1924, in Pittsfield, VT to Franklin Sulham and Mary Wescott. Olive grew up in Pittsfield, leaving ... remainder of obit for Mary Olive Tracy

Malcolm L. Stevens

Malcolm L. Stevens

Lebanon, NH - Malcolm L. Stevens, age 93, passed Wednesday, April 24, 2024. Family and friends are invited to Malcolm's calling hour from 11 to 12 Monday May 6th 2024 at the Ricker Funeral Home in Lebanon. A memorial service will be... remainder of obit for Malcolm L. Stevens

Corinne Moore

Corinne Moore

Fairlee, VT - Corinne (Godfrey) Moore, long time resident of Fairlee, VT, passed away peacefully on April 25th, 2024, after a short stay at the Jack Byrne Center in Lebanon, NH. Born in Post Mills, VT to Mary and Winston Godfrey, Corin... remainder of obit for Corinne Moore

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

New Hampshire jury finds state liable for abuse at youth detention center and awards victim $38 million

New Hampshire jury finds state liable for abuse at youth detention center and awards victim $38 million

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties

Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties