Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

CLAREMONT — In identical 5-3 votes Wednesday, the City Council removed Jonathan Stone from two committee appointments based on a recently released report alleging he threatened to murder and rape fellow officers and their family members while working...

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

The Valley News was born in 1952 and so was I. This is probably coincidence, but I like to think there is more to our association than the fact that we are both from the year of the water dragon in the Chinese calendar.According to the Internet,...

Most Read

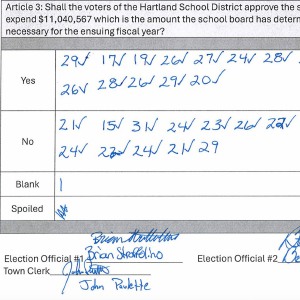

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Editors Picks

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Sports

Woodstock boys lax defense steps up, holds off Hartford

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — Monday night’s boys lacrosse game between host Hartford High and Woodstock came down to the final minute, with the Wasps prevailing, 11-10.The Vermont inter-division clash might have been decided, however, by a pair of goals at...

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

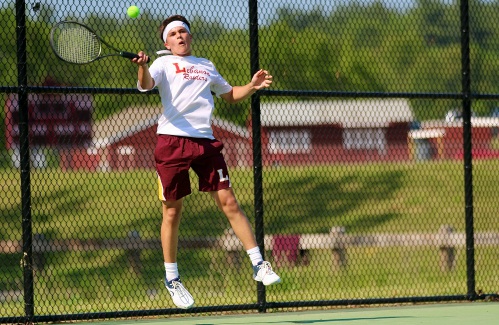

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

Opinion

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Hey, Major League Baseball, does the name Pete Rose ring a bell? Remember him, “Charlie Hustle”? One of the game’s greatest players, whom you banned for life in 1989 because he bet on baseball games?We ask because you have on your hands another...

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

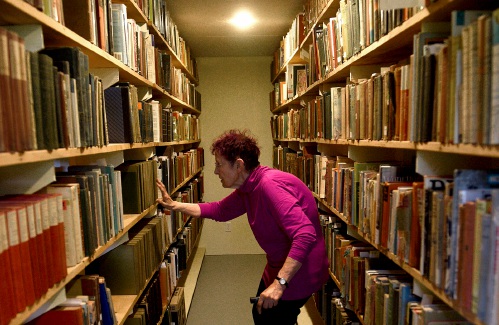

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

Photos

Clear and free in Hartford

Ramping up their foraging

Ramping up their foraging

Roadside assist in Bethel

Roadside assist in Bethel

Preserving habitat in Etna

Preserving habitat in Etna

Pitching in

Pitching in

Arts & Life

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions, the White River Junction theater company that has championed the work of Black, queer and trans artists, announced last week that it is closing in June after eight years of bringing groundbreaking work to the Upper Valley.Jarvis...

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Obituaries

Donna Trottier

Donna Trottier

Wilder, VT - In Loving Memory of Donna Trottier aka Felicia D. Hinds It is with heavy hearts that we announce the passing of Donna Trottier, a beacon of fierce love, kindness, and generosity, who departed this world just a week before ... remainder of obit for Donna Trottier

Marla Polonco

Marla Polonco

Barre, VT - It is with great sadness that the family of Marla (Neily) Polonco announces her passing January 30, 2024 at age 45. Marla was predeceased by her mother Deborah Ashton. She leaves behind her father and stepmother, Phil and L... remainder of obit for Marla Polonco

Richard Pariseau

Richard Pariseau

Newport, NH - Richard N. Pariseau, 93, of Newport, NH, passed peacefully at his home, April 16, 2024. Dick was born and spent his full, robust life in Newport. Dick married Betty Gilson and enjoyed 70 years of marriage before her pa... remainder of obit for Richard Pariseau

Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Adrian W. Frary, Jr. Tunbridge, VT - Adrian W. Frary, Jr., age 98, passed Wednesday, April 3, 2024. Calling hours will be held on Saturday, April 27, 2024 from 6 to 8pm at the Boardway and Cilley Funeral Home in Chelsea, VT. A graveside... remainder of obit for Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Local Roundup: Lebanon baseball, softball teams fall to Bow

Local Roundup: Lebanon baseball, softball teams fall to Bow

In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary

In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary