Three vie for two Hanover Selectboard seats

HANOVER — Three people are vying for two three-year terms on the Hanover Selectboard in Town Meeting voting next week.Voters will be asked to choose from a slate including Kari Asmus, Jarett Berke and incumbent Joanna Whitcomb, the acting Selectboard...

NH troops from the border: ‘We have to adapt every night to every scenario’

New Hampshire National Guard Lt. Ryan Camp looked through the border fence separating Texas and Mexico, and made a mental note of the pickup truck crawling back and forth along the bank of the Rio Grande. He logged the man fishing and the person he...

Most Read

Killington is the East’s largest ski resort. A developer wants to expand on that in a big way.

Killington is the East’s largest ski resort. A developer wants to expand on that in a big way.

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Claremont movie theater to close at end of May

Claremont movie theater to close at end of May

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Dartmouth moves swiftly to stymie demonstration, leads to 90 arrests

Dartmouth moves swiftly to stymie demonstration, leads to 90 arrests

Editors Picks

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Editorial: Response to campus protests only adds fuel to the fire

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Kenyon: Dartmouth shows it has no patience for peaceful protest

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Publisher’s note: Valley News launches updated online app

Sports

Hurricanes earn 10-9 victory over U-32 in girls lacrosse

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — The pass was perfect, a classic backdoor feed that arced from Paisley Danaher to Madison Barwood and resulted in the winning goal Saturday for the undefeated Hartford High girls lacrosse team.The strike lifted the host...

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Stevens, Newport baseball split high-scoring games

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Lebanon High senior comes to the aid of driver with health problem

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Oxbow softball at dynastic, dominant best

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Local Roundup: Lebanon wins big over Bow in boys tennis

Opinion

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu’s conversion from “Never Trump” to “Ever Trump” occurred not on the road to Damascus but on the Republican Party’s road to perdition.On ABC News last Sunday, Sununu affirmed his intention to support Donald Trump for...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

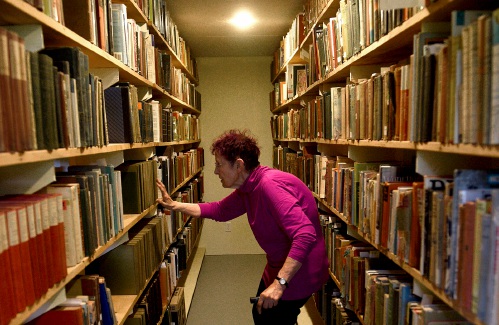

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Afternoon outing in Norwich

In the garden

In the garden

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Spring cleanup in Lebanon

Drawn to dragons

Drawn to dragons

Clear and free in Hartford

Clear and free in Hartford

Arts & Life

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

When Peter Stickney walks along his cow paddocks in the morning, he notes the scattered patches of greener grass across the pasture. He knows what this means: It’s where his cows have peed. So when the Rich Earth Institute, a Brattleboro organization...

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Obituaries

Brian A. Button

Brian A. Button

Chelsea, VT - Brian A. Button, age 82, passed Friday, December 15, 2023. A funeral service for Brian will be held Saturday, May 11, 2024 at 1pm at the United Church of Chelsea, VT. Burial will follow in the Highland Cemetery. To vie... remainder of obit for Brian A. Button

Richard Sweet

Richard Sweet

Hartland, VT - Richard "Ricky" Michael Sweet, 67, died May 1, 2024, at Hanover Terrace in Hanover, NH where he has been a resident for the past several years. He was born October 26, 1956, to Neil Sweet Sr. and Vena (Besaw) Sweet. R... remainder of obit for Richard Sweet

Thomas Arthur Bubolz Ph.D.

Thomas Arthur Bubolz Ph.D.

Thomas Arthur Bubolz, PhD Grand Junction, CO - Thomas "Tom" Arthur Bubolz, PhD., 82, passed away peacefully on May 1, 2024 in Grand Junction, CO, after a long illness. Tom was born in Maywood, IL, to Arthur and Georgeanna Bubolz. He earn... remainder of obit for Thomas Arthur Bubolz Ph.D.

Vernona Bell

Vernona Bell

White River Junction, VT - Vernona S. Bell, age 83, passed Saturday, May 4, 2024. A full obituary will be published in an upcoming edition of the Valley News. Knight Funeral Home in White River Junction has been entrusted with a... remainder of obit for Vernona Bell

Hartford Selectboard considers banner policy amid controversy over ‘Hometown Heroes’ project

Hartford Selectboard considers banner policy amid controversy over ‘Hometown Heroes’ project

Local Roundup: Bears defeat Hollis-Brookline in softball slugfest

Local Roundup: Bears defeat Hollis-Brookline in softball slugfest

NH Senate President Jeb Bradley to retire after a 32-year career in politics

NH Senate President Jeb Bradley to retire after a 32-year career in politics

David Zuckerman is seeking reelection to lieutenant governor’s office

David Zuckerman is seeking reelection to lieutenant governor’s office

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community  Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties

Out & About: Newport art center’s exhibition celebrates homes of all varieties