Column: The age-old question of what to read

|

Published: 04-05-2024 5:32 PM

Modified: 04-08-2024 10:36 AM |

How many times have I heard someone say, “Books are dead, no one reads anymore”? It may be true that reading habits have changed (I’d argue that young people who spend a lot of time online are actually reading a lot.) and that there has been a steady march of newspapers and magazines to a digital format.

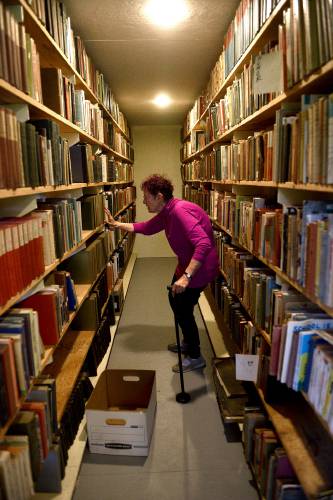

But spend a little time in an independent bookstore listening to conversations as people browse, and you will feel the echo of Mark Twain’s famous words from 1897, “The report of my death was an exaggeration.” Books aren’t dead. The real problem is that there are so many of them to read.

Fifteen years ago, as my wife and I prepared for retirement and a move from a spacious house in Massachusetts to a smaller one in Vermont, we had to reduce the things we owned by a good two thirds. The shedding involved furniture, clothing, appliances and everything hanging on our walls. For me the most painful part involved the books I had been collecting since college. They were a key to my identity, and so many of them had been gifts.

What surprised me was how the process illuminated what I valued. Fiction dominated the books I kept, then poetry and drama. The nonfiction books I saved were mostly philosophical, often the writings of critics. I couldn’t part with literary biographies. What I did with the other two-thirds of my books (I threw nothing away) is less important than that I believed I could live without them. I emerged from the culling with a clearer sense of who I was, heading into this next stage of my life.

The dilemma I describe is anything but unique; anyone who has moved from one spot to another has had to make similar choices. In his collection of stories “The Things They Carried” (a book that made my cut), Tim O’Brien makes the same connection between objects and identity, although he was writing not about retirement, but about the young and about war. The point is that we are all unique, and the things we keep are deeply personal.

Long ago I realized that there are more books than I could ever read, a discovery that is at once humbling and liberating. No matter how widely and deeply I read, there will always remain some books I believe I should read. I refer not to the canon (I have come to believe there is no such thing), but to my own personal list of books I have always intended to read; and each year it becomes clearer that I am unlikely to get around to “The Tale of Genji” or “Gravity’s Rainbow.” And, of course, 15 years ago as I culled my books, I realized that even if I lived to 100, there would not be time enough to reread all the ones I did save.

This gnashing of teeth leads me to an inevitable question: what, then, to read? I have an old friend I have known since we were 14 and roommates in boarding school. We went to different colleges and graduate schools, and our careers as teachers led us to opposite sides of the country, but through the years we have kept in touch. These days we exchange emails that resemble old-fashioned letters, often about the books we are reading. He is the most dedicated re-reader I know and would be happy spending the rest of his life rereading Chekov, Rumi, and St. Augustine. Occasionally, he will try something new, perhaps something I have recommended, but it’s unlikely to be a book that he will reread. There is a sweet practicality to his system. He is never without a good book, and he knows, with the wisdom of a good teacher, that each rereading brings fresh insight.

There is no system to the way I read, but I will say that I am curious about the new. I read book reviews in the Sunday Times, and always there is something that interests me. Friends recommend books to me. My wife does as well; our tastes are different, but not that far apart, and we have been exchanging books since we were in college. I have always been a random reader, one book leading to another, sometimes a good one leading to a terrible one, and the other way around. Only rarely will I not finish a book I have begun. I like reading about places I will never go and people I will never meet, and the more I read, the closer I come to understanding myself.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

My old friend and I may read differently, but what we are in search of is remarkably similar. Long ago we abandoned the hope that we could read everything we think we should; sometime after that we abandoned the notion that the word “should” has any value when it comes to reading. Similarly liberated, we have gone in our different directions, both in pursuit of what interests us personally. Like Thoreau, we are off on a long trek with no destination other than walking itself. Listen carefully the next time you are in a bookstore or library, and you will realize that there are a lot of others out there just like us.

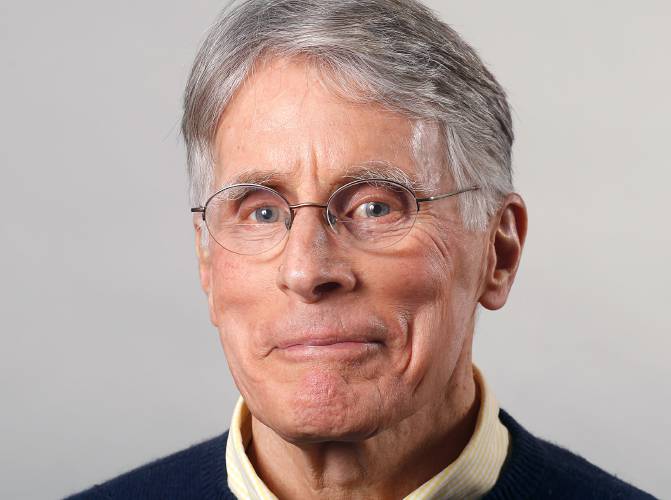

Jonathan Stableford lives in Strafford.

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling