Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

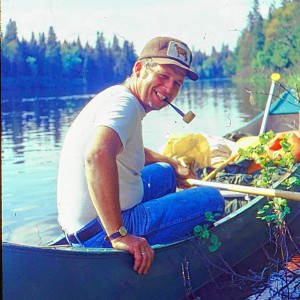

Standing between two tables, Claremont City Councilor Jonathan Stone, left, watches votes being counted with incoming city councilor Jonathan Hayden at City Hall in Claremont, N.H. on Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2023. Hayden defeated Stone last week for the Ward III seat 247-241. Stone asked for a recount of the results, which did not change. Assistant Mayor Debbie Matteau and Ward III Moderator Bill Blewitt, right, count votes as Keith Raymond observes.(Valley News - Jennifer Hauck) Copyright Valley News. May not be reprinted or used online without permission. Send requests to permission@vnews.com. Jennifer Hauck

|

Published: 03-29-2024 8:01 PM

Modified: 04-08-2024 10:33 AM |

It’s hard to think of a better argument for disclosure of police disciplinary records than the case of Jonathan Stone, ex-cop, former city councilor and for the present, a New Hampshire state representative.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court earlier this month cleared the way for the release of Stone’s records, ending a long court battle. As of this writing, we don’t know what those records contain, but in ruling for their release, we think the court breathed effective life into the preamble to the state’s Right-to-Know law: “Openness in the conduct of public business is essential to a democratic society. The purpose of this chapter is to ensure both the greatest possible public access to the actions, discussions and records of all public bodies, and their accountability to the people.”

Stone was a Claremont police officer for six years in the early 2000s and agreed to resign in 2007 as part of a confidential agreement with the city negotiated through his union. The agreement resolved four grievances Stone filed in response to a number of internal affairs investigation reports. How confidential was it? The parties agreed “to keep the existence, terms and substance” of the agreement confidential, except to the extent required “by an order of some other agency, court of competent jurisdiction, or by law.” In other words, its very existence was intended to be non-existent as far as the public was concerned.

No doubt resorting to these kinds of secret agreements makes life easier for government entities that just want to make a problem go away, but they strike at the heart of accountability. More on that in due course.

In 2020, free-lance journalist Damien Fisher sought disclosure of Stone’s records under the Right-to-Know law, following a couple of state Supreme Court decisions that allowed disclosure of some internal records related to alleged police misconduct.

Stone then went to court to block release of the documents, including 13 internal affairs investigation reports and four sets of correspondence between the New Hampshire Police Standards and Training Council and the city of Claremont, arguing that their disclosure would violate his secret agreement with the city and would constitute an invasion of his privacy.

When the case finally arrived at the Supreme Court, the justices unanimously upheld a lower court ruling that the reports and correspondence were public records under the law, emphasizing that the confidentiality agreement provided for disclosure as “required by law.”

The reasons for disclosure of disciplinary records are many. The public has a compelling interest in knowing about substantiated allegations of misconduct by police officers whom they employ with their tax dollars. Moreover, government entities cannot be held accountable for their actions if those actions are shrouded in secrecy. Understanding how the city of Claremont and the Police Standards and Training Council handled Stone’s case is critical to determining whether they performed their duties in accord with the public interest.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

Finally, in this case voters deserved to know about Stone’s record as a police officer before they cast ballots in elections in which he was a candidate. Indeed, in 2020, he sought an injunction in Superior Court, arguing that because he was, at that point, a Claremont city councilor and a candidate for the Legislature, public disclosure of the records would cause him irreparable harm. Although he was defeated for re-election to the Claremont City Council last fall, he continues to represent a House district made up of Claremont and eight other municipalities.

The claim that privacy interests of police officers preclude disclosure of these kinds of records deserves to be met with skepticism. Anyone who wears a badge, carries a gun and has authority to deprive citizens of their liberty has scant basis for such a claim. With great power comes great responsibility, and the public deserves to know how that power is exercised. Properly understood, privacy in this context should be limited to personal information such as health records.

As heartening as the Supreme Court’s decision was, it contains a troubling concurrence by Associate Justice Anna Barbara Hantz Marconi in which she expresses concern that the decision may be an incremental step toward precluding the use of confidential settlements by government entities, which she asserts “can serve an important purpose.”

To the contrary, these types of confidential agreements are designed precisely to limit access to information to which the public is entitled, and their use should be restricted to rare instances rather than being relied on as a routine tool to resolve difficult public employee personnel problems.

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths