Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

LEBANON — Riddell Sports, which makes the helmets worn by more than 75% of players in the National Football League, has purchased Simbex, a Lebanon-based company that revolutionized the monitoring of head impacts in athletics.The purchase price was...

Through new school partnerships, CRREL seeks to educate young scientists

LYME — On a raw, not-quite-spring New England afternoon, four seventh and eighth graders in the New Hampshire Academy of Science’s (NHAS) after-school program clustered around a computer, choosing images of orchids for a poster they’re designing to...

Sports

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

Once you’ve finally been to the top of the mountain, what do you do for an encore?That’s the challenge facing the Hartford High boys lacrosse program this spring. After multiple attempts that came up short, the Hurricanes ran the table en route to...

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Windsor baseball’s annual gauntlet begins with Hartford defeat

Windsor baseball’s annual gauntlet begins with Hartford defeat

2024 Upper Valley high school baseball guide

2024 Upper Valley high school baseball guide

Ex-Virginia assistant Kirwan latest to step into the Big Green breach

Ex-Virginia assistant Kirwan latest to step into the Big Green breach

Opinion

A Yankee Notebook: An inevitable and terminal move

Living three and a half hours apart, as we do, my dear friend Bea and I get to see each other about every two weeks or so, on average. This is almost without doubt an ideal arrangement, as our lifestyles are quite different, and neither of us could...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

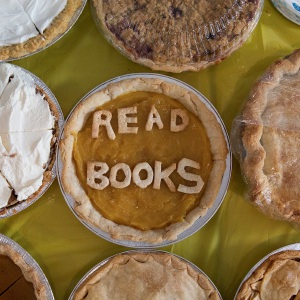

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Acoustic music jam in White River Junction

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Arts & Life

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

It was Traffic vs. the Eclipse on Monday, a showdown of celestial proportions. Would I risk everything like Marco Polo who bravely set out to see the world, or follow the example of his brother Rocco, who said their hometown of Venice was “plenty good...

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Sunshine, snacks and laughs features of Bugbee’s solar eclipse party

Sunshine, snacks and laughs features of Bugbee’s solar eclipse party

Obituaries

Lisa Gurney

Lisa Gurney

Newbury, VT - Lisa Marie Gurney, age 55, passed Thursday, March 7, 2024. There will be a graveside service on Thursday, May 2, 2024, at the New Oxbow Cemetery in Newbury, VT, at 10 AM. ... remainder of obit for Lisa Gurney

Megan Mattern

Megan Mattern

Midland, TX - Megan Mattern, 44, passed away on March 15, 2024, at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, after a valiant fight with cancer. Born December 6, 1979 to Wes and Susan Mattern, Meg... remainder of obit for Megan Mattern

James R. Thibodeau

James R. Thibodeau

Leland, NC - James R. Thibodeau, age 75, passed Saturday, April 13, 2024. A full obituary will be published in an upcoming edition of the Valley News. Ricker Funeral Home has assist... remainder of obit for James R. Thibodeau

Beverly Vaughan

Beverly Vaughan

East Thetford, VT - Beverly Vaughan, 76, of East Thetford, VT, died unexpectedly on Sunday, April 14, 2024. She was born on December 18,1947, to Floyd and Bessie (Minor) Dexter. She gre... remainder of obit for Beverly Vaughan

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

With less than three months left, NH casino hasn’t found a buyer

With less than three months left, NH casino hasn’t found a buyer

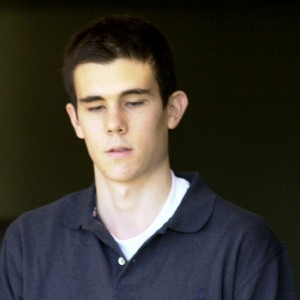

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

A former NH youth detention center resident testifies about ‘hit squad’ attack

A former NH youth detention center resident testifies about ‘hit squad’ attack

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes

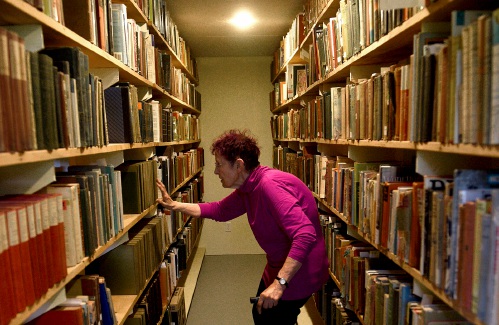

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’ Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show