Column: Tending Wilder’s Grave, and His Memory

| Published: 06-03-2016 10:00 PM |

What The Thornton Wilder Society recently did would have been unthinkable many years ago. It announced that Wilder, who died in 1975 as America’s most honored writer (three Pulitzers and a National Book Award) had lived his life as a “deeply closeted” gay man. It invited scholars in a “call for papers” to propose topics for a panel discussion entitled “Queer Readings of Thornton Wilder,” a reference to the literary title used in gay studies.

Wilder would be spinning in his grave with a cigarette in his mouth and a scotch in his hand. He was born in 1897, and for his entire life, gay sexual activity was a crime punishable by imprisonment in most states. He lived in the shadow of a prominent New Haven/Yale family, whose members would have felt disgraced by even the whiff of scandal.

Full disclosure: Thornton Wilder is buried 100 yards from my parents in Hamden, Conn., and I used to maintain his grave for his sister when she was in her 80s. Once, slugs ate the flowers and buds off a potted marigold I had planted in front of his marker, and the florist told me to fill a plastic cup with beer and submerge it in the ground for the slugs to drink from and drown. I must have looked quite odd with a bottle of beer standing over Thornton Wilder’s grave pouring the contents near his tombstone, but I did as instructed. He would have enjoyed the scene. By the way, it killed the slugs.

I was with his sister, my friend and neighbor for 20 years after he died, when she reacted to the manuscript of Wilder’s official biography submitted to her months before its 1983 publication. It contained a chapter alleging Wilder may have had a secret life as a gay man. Others had made such allegations, but this was “the official biography” authorized by the family.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

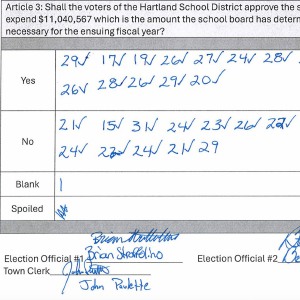

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

She brushed it off and deflected it with what the military would call a diversionary tactic. “I’m an old lady (83 in 1983). I’m reading along and I come across some old homosexual experiences they found that Thornton had. They gave me no warning. I’m an old lady. I can’t be treated that way.”

She had successfully changed the subject from his homosexuality to her “ladyhood.” When she was asked to make a toast at the dinner celebrating the publication of that official biography and its author, Gilbert Harrison (The Enthusiast: A Life of Thornton Wilder), she told me with pride how she punished the author with the etiquette of a lady: “I toasted the man, but I never mentioned his book.” That’s class — and a punishment so diluted by manners that the victim might miss it.

Indeed, Harrison later told my friend, the late Paul Moore, Episcopal Bishop of New York, that he always “wondered what Isabel’s reaction to that chapter was.” I was able to tell them.

Miss Isabel Wilder, like her brother, Thornton, never married. She was born in 1900 and lived to age 95 in 1995, so it was always easy to know how old she was. She wrote novels herself, and became the literary executor of Thornton’s estate after he died. That included two blockbusters — Our Town, the most formed play in the American theater, and The Matchmaker, which had been made into the delightful musical (and cash cow) Hello Dolly.

It is ironic that this bachelor wrote the most famous wedding scene in American literature, if not all literature, the George and Emily Gibbs marriage in Our Town.

Note that the minister in the play says, “People are meant to live two by two” and later says, “I’ve married over two hundred couples in my day. Do I believe in it? I don’t know, M marries N, millions of them.” Both comments are gender-neutral (“people” and “M” and “N”) and could apply to the 2016 phenomenon of gay marriage as well as traditional marriage, 41 years after Thornton Wilder’s death. Was such language an example of a closeted gay man being cagey in 1928, the year Our Town was published?

It was my good luck to be Miss Wilder’s friend, and the beneficiary of her grandmotherly indulgence, when I was a penniless Yale graduate. She paid for my internship to become a Vermont public school teacher in 1985, and she paid for the first year of my M.A. at the Bread Loaf School of English in 1992, a school which she herself had attended 60 years before.

In my eyes, she rocked — even if she was an “old lady.”

There’s a reason I think Miss Wilder would not be scandalized that The Thornton Wilder Society has put out a call for papers on Wilder under the field of queer studies.

In 1984, almost before AIDS had an official name, I was working with a group at Yale who published a pamphlet on safe and unsafe sex, and discovered there was a prostitute in New Haven who was the first woman in America known to have transmitted AIDS heterosexually, but patient confidentiality prevented Yale-New Haven Hospital from disclosing her existence and her medical condition. Previously, AIDS was thought to have been a “gay disease.” Yale refused to distribute the pamphlet on unsafe sex to its students (it was graphic), so I announced I would do so at my own expense.

“My own expense” was actually Miss Wilder’s expense. She offered to pay for it on the condition that I never reveal her participation while she was alive. Two decades after her death, I acknowledge her sponsorship.

She may have saved several lives and prevented much suffering in New Haven and elsewhere. No, she would not be spinning in her grave.

Miss Wilder would have reacted to the Thornton Wilder Society’s call for papers with the same ladylike aplomb she did to the chapter in his official biography in 1984.

I can hear her now, changing the subject and speaking from the grave like Emily in the cemetery scene from Our Town: “I’m a lady. And I’m dead. They should have warned me ahead of time about these modern matters.”

Paul Keane lives in Hartford.

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths