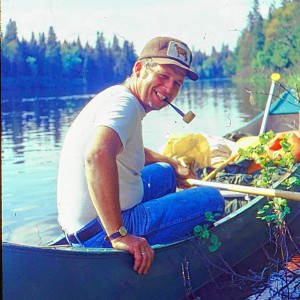

A Life: Anthony Rocchio; ‘He celebrated other people and their lives’

| Published: 02-20-2023 9:21 AM |

WINDSOR — For Anthony Rocchio, human encounters and connections were more than an opportunity to forge new friendships. They were a cause for celebration.

Rocchio’s natural gift for engaging others and wanting to learn about them brought him his greatest joy in life, says his family.

“He celebrated other people and their lives,” said his oldest daughter, Anne Rocchio-Dodge, a teacher in New Boston, N.H. “When he said students’ names, professors’ names, names of anyone he met, in any experience in life, he said their names with such reverence. They were phenomenal people in his eyes.”

Even the disagreeable were special in Rocchio’s estimation.

His youngest daughter, Mia Donata Rocchio, wrote in a college essay that her father “perceives the ill-tempered as a delightful challenge; his chance to ‘make them feel good.’ This man seems blind to any negative trait a human being may possess.”

Anne recalls receiving a letter from her father while she was away at ballet school that revealed his guiding philosophy.

“I opened this letter on yellow lined paper, and I still remember this line he wrote: ‘Remember, people discovery is the greatest gift in life,’ ” said Anne, the oldest of five Rocchio children. “It is a valuable gift to have someone who teaches you to celebrate others without judging them,” she said.

Rocchio died on Oct 8, 2022, about two months shy of his 89th birthday, after a years-long battle with Alzheimer’s.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

He was born and raised in Rhode Island. After graduating high school, Rocchio briefly attended Norwich University before leaving to join the Army at 18 during the Korean War. He was sent to Japan as one of the last post-World War II occupation forces and conducted search and rescue missions on Mount Fuji.

His son David, who lives in Stowe, Vt., said his father fell in love with Japan and the culture. Back home, Rocchio earned a degree in English from the University of Rhode Island and later a masters in English literature.

“He was kind of a Renaissance man,” said his friend, Star Johnson, owner of Big Green Realty in Hanover. “You could talk to him about anything from poetry to literature, Faulkner, sports, music. He was an interesting guy, a sweet guy. It was impossible not to like him.”

He came to the Upper Valley in the early 1970s and taught English and drama at Hanover High School.

“Some 50 years later, and I am still thinking about Anthony and feeling his impact,” Virginia Quinn, a former student, said. “One of the best teachers I had. He had a deep interest in people and accepted all his students without judging them.”

Passion and curiosity about the world is what set him apart, Quinn said. “He didn’t teach by dryly imparting knowledge; he swept his students up into this world of passion for his subject.”

Rocchio taught a course on the works of William Faulkner, a focus of his masters degree, that Quinn said was challenging but students still “flocked to the class.”

“I never fully understood the novels but, the summer after the course, I was visiting my grandmother in Tennessee and convinced her to drive me to Oxford, Mississippi, where his novels were based,” Quinn said. “Anthony’s enthusiasm inspired a great road trip and inspired me to explore a different world.”

As Hanover’s football coach in the 1970s, Rocchio built a team that one year defeated archrival Lebanon for the first time in more than 30 years, said his son Paul, who lives in Boise, Idaho, and followed in his father’s footsteps as a high school coach, including football and lacrosse at Woodstock.

“Hanover football was on its heels,” Paul said, “When he became coach, he reached out to Dartmouth coaches to get some ideas, and they sort of adopted him.”

His dad would hold pasta dinners for the players and parents before games. When he discovered an Italian restaurant in Northfield, Vt., Rocchio would bring the entire Dartmouth basketball team there for dinner.

“They would hang out and talk for hours,” Paul said.

Paul played for his father and while he learned about offensive and defensive schemes, he remembers another lesson that he carried with him in his coaching life.

“When I was a freshman, he told us, ‘Everything we do, we do as a team,’ ” he said.

While playing freshman football, Paul, the team captain, said he got the idea to create a different look and one afternoon bought some maroon electrical tape at a local hardware store to put on the helmets. But not all the players sported the maroon stripes. On the field, his father noticed something different right away; Paul had violated his dad’s team credo.

“He was less than pleased,” Paul said. “That became a very interesting lesson for me.”

After Hanover, Rocchio headed back to Rhode Island in 1979 as academic adviser to the Providence College basketball team.

“Don’t knock the Roc,” said Providence coach Gary Walters, when asked about his friend.

Walters said he and Rocchio and several others with a shared love of basketball became close friends while he coached Dartmouth.

“Given the fact he was an English teacher, when I went to Providence College the notion of kids being held accountable academically was important to me, and I asked Anthony if he would like to come to Providence,” Walters said. “He was just a wonderful guy. He was so kindhearted and a terrific teacher and coach.”

Daughter Tina saw his kindness and ability to connect with others during his time at Providence, when she was a freshman at a prep school. She watched him mentor the athletes with passion and commitment and recalls his relationship with Otis Thorpe, a 7-foot-tall freshman from Florida. After Sunday morning stops for breads and pastries, they would pick up Thorpe and go over to her grandmother’s house for Sunday dinner.

“Otis would fold himself into Dad’s new Celica like an intricate piece of origami and come to Sunday dinner with us, warming to our family as he longed for the one he left behind in Florida,” Tina said at her father’s eulogy. “By watching Dad with his players, I learned the invaluable gift of mentoring.

“I saw what it really is to mentor unlimitedly,” Tina said. “He just really believed in the human connection. Even as he courageously lived with Alzheimer’s, he sought people out to engage them.”

After his retirement in the late 1990s from teaching at Springfield High School, Rocchio worked with his wife, Cynthia, as a volunteer at the Dartmouth gym, which allowed him to continue those connections he so deeply cherished.

“It was another way for him to connect with people in the valley, and he loved it,” said Tina, who lives in Rome. “He was in his late 70s and early 80s and was going up to the gym to open it at 4 a.m. He would take the early shift and was greeting everyone as they came in. I would sometimes go when I was visiting and see him engage with everyone.

“I learned from him to find a level of connection with everyone in every walk of life,” Tina said.

In retirement, he also helped out the Windsor football team.

“He loved being with the kids,” Cynthia said. “He got to know a lot of kids all over the Upper Valley. We would see them at times in restaurants, on the street, in the grocery store. They would come up to him and give him a hug and just be really happy for his presence in their lives.”

Larry Carbonetti, a Springfield High teaching colleague, said Rocchio’s impact on students cannot be overstated. Carbonetti recalled a conversation less than two years ago with a student, now living out west, who had a leading role in a performance of The Glass Menagerie, directed by Rocchio, in 1990.

Carbonetti shared that Rocchio was ill and battling dementia. A few weeks later, Carbonetti received a link to a video produced by the student and four others who were in the play.

“They rehearsed their parts and performed the play for Anthony,” Carbonetti said. “And they did not just read the parts. It was a remarkable performance. At the end, they each made a personal statement of how much Anthony meant to them in their lives.

“That is the sort of thing he engendered in people,” said Carbonetti, who said the course he co-taught with Rocchio was the best experience of his 30-year teaching career. “For these students to look back after 30 years of life with their jobs and families today and remember how significant Anthony was when they were 17- and 18-year-olds is remarkable.”

David and Tina said their father always wanted to be a writer and in a sense he was, but not on paper.

“No matter how little he published, I think he wrote a novel a day in his mind,” Tina said. “I learned to communicate with and find a level of connection with every walk of life.”

At a celebration of his father’s life in December, David talked about a summer trip with his father in 1971 that took them to Amarillo, Texas, then north to Colorado Springs, Colo., where Rocchio did his basic training, and into Wyoming.

“In Cheyenne, in a cowboy store, he embarrassed me by striking up a conversation with a huge man at the cash register,” David said. “He talked with that man for about an hour. A man my dad had no shared experience to talk about. Just being alive. They had the best time. It made me smile.”

Patrick O’Grady can be reached at pogclmt@gmail.com.

Lebanon moves forward with plans for employee housing

Lebanon moves forward with plans for employee housing Howard Dean weighs (another) run for governor

Howard Dean weighs (another) run for governor Colby-Sawyer president announces plan to depart

Colby-Sawyer president announces plan to depart