Windsor grapples with evidence that a major figure in town, Vermont history was a slaveholding scofflaw

| Published: 07-25-2020 9:33 PM |

Little is known for certain about the life of Dinah Mason, but a few facts now seem incontestable.

A bill of sale from 1783 shows that Dinah, who was Black, was purchased by Windsor resident Stephen Jacob from a Charlestown man named Jotham White.

Additional records unearthed by Windsor resident James Haaf and others indicate that Dinah lived in Jacob’s house, most likely to care for his children, until she was turned out to fend for herself as she was sick and going blind. The town sued Jacob in 1802, saying he should be responsible for her care, but two justices of the state Supreme Court sided with Jacob, who was the third justice.

They found that because slavery was illegal in Vermont, Dinah could not have been a slave.

And so the buried history would have remained, if not for a new round of investigation that has led Windsor to revisit Dinah Mason and her story.

The Selectboard is weighing whether to rename Jacob Street, both to elevate Dinah’s story and to remove Jacob’s name from a prominent spot on State Street. And the state plans to erect a historic marker about Dinah next year, on Juneteenth, the day of historic celebration of slavery’s end.

Historic Windsor put up its own marker in front of the house, at 70 State St., on Juneteenth last month, which identifies her only as Dinah. She has sometimes been called Dinah White, but Haaf said his research proves her name is Dinah Mason. In talking about her, Windsor residents use her first name.

The conversation is a bit of a reappraisal of Windsor’s history, and Vermont’s. The 1777 constitution that made Vermont an independent republic and the first state to outlaw slavery was drawn up in Windsor, so the idea that a man who was instrumental in the state’s early years might have held a woman in de facto slavery leaves an especially bitter taste.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

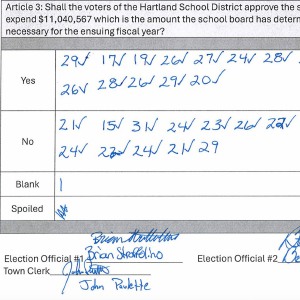

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

“Let the residents of Windsor now show how morally evolved we have become, and have committed ourselves to being, by not letting Dinah be forgotten,” Selectboard member Amanda Smith said at the board’s meeting on June 30, when it took up the question of renaming Jacob Street.

Haaf stumbled onto the story of Dinah Mason by accident. He bought a house in Windsor 20 years ago that had been on Jacob’s property. “I started tracing the ownership of it, and that of course led me to the story of Dinah Mason,” he said in a phone interview.

Jacob, who had attended Dartmouth College, moved to Windsor after completing his education at Yale University. Vermont was then a frontier and seen as fertile ground for settlers seeking their fortune. He opened a law practice and had built what was then the grandest house in town.

Haaf, who worked as a gardener at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Park for 20 years, has traced Mason back to family in Connecticut. He believes she was American-born. How she came into the orbit of Jotham White is unclear.

“He was a wheeler-dealer,” Haaf said of White. It’s possible she never set foot in Charlestown but was moved on straight to Jacob when she was around 30 years old. White was known to have sold at least one other person, an 8-year-old boy, to a Springfield, Vt., resident, according to Haaf.

What Dinah’s life was like is also a mystery. Though Jacob’s name is on the bill of sale, his wife, Pamela Farrand, would have maintained the household while Jacob was traveling as a lawyer, a legislator, a jurist and a prosecutor, Haaf noted. He has uncovered evidence that Farrand would not have been comfortable keeping slaves. Whether that meant Dinah had a measure of freedom is unclear.

Church records that Haaf has examined indicated “she was abused by a man who was most likely in a position of authority,” but that it was not Jacob. Haaf hesitated to call it rape, because the records say “abuse,” but he thinks it’s likely she was raped. It appeared to have occurred while she was living in another home in town; whether because she went freely to work there or was hired out by Jacob is unclear, Haaf said.

While this was happening, Jacob, who was originally from western Massachusetts, became a grandee in his adopted state. He served in town and state government and after Vermont was admitted to the union, in 1791, he became the state’s first U.S. Attorney, appointed by George Washington.

Although Vermont had abolished slavery, the institution persisted, and Jacob wasn’t the only example of people who held slaves in defiance of the state constitution, said Harvey Amani Whitfield, a University of Vermont history professor who gave a talk in Windsor last year. He is the author of The Problem of Slavery in Vermont, 1777-1810, which includes a chapter about Dinah.

“It persisted in two distinct ways. First, masters defied the law by purchasing and selling slaves and holding slaves, and that’s Stephen Jacob, right? He clearly has Dinah; he’s holding her for 17 years or so, and he knows he’s not supposed to do it. How do we know he knows? Because he’s a lawyer, he’s on the Supreme Court. ... We have to hope he knew that,” Whitfield said in his talk, which was taken from his book.

“The limited evidence does not point to slaveholders exhibiting any sort of embarrassment in breaking the law. Indeed, those individuals who continued owning slaves included some of the most respectable citizens in the state, ranging from judges to military officers. Second, some white Vermonters styled African Americans as servants, but this was merely a euphemism to hide the fact that these people were literal chattel slaves or de facto slaves.”

The Vermont Legislature continued to pass laws against slavery, in part because the practice continued.

This was the backdrop for a legal battle over Dinah in which the town sued Jacob, claiming he had a duty to pay for her support when she became ill.

Haaf said it’s unclear whether Jacob turned Dinah out of his house in 1800 or whether she left, but in any event, the town considered Dinah to be Jacob’s property. The town sought to enter the bill of sale into evidence. A sheriff made a copy and Jacob attested to its accuracy, Haaf said. (The original has been lost, Haaf said.)

“The selectmen of Windsor only brought suit when Dinah’s freedom became a burden to the public treasury,” Whitfield said, “not out of any sense of outrage that Judge Jacob had illegally enslaved her.”

Jacob, who was a member of the Vermont Supreme Court in 1801 and 1802, had to recuse himself from hearing an appeal of the case. The two justices decided in his favor in 1802 and didn’t admit the bill of sale as evidence. The town withdrew its case and never resubmitted it.

“In an argument of amazing hypocrisy, Judge Jacob’s counsel claimed that his client did not attempt to retrieve his slave because of his obedience to the constitution, because Jacob believed he could not legally hold her as a slave, this in spite of the fact that he had done so for the better part of two decades,” Whitfield said, adding that Jacob said the best solution was for the Selectboard to turn Dinah out of town, which they tried to do a few years later.

“His attorney concluded that the real question hinged on whether the defendant was obligated to refund monies advanced by others for the care of his former slave in a state where the principle of slavery ‘cannot be admitted.’ ”

There are receipts that show that Jacob paid some of Dinah’s medical bills, and that she paid some of them herself. She was part of the fabric of the town, and there would have been people who knew her and cared for her, Haaf said.

“She very likely had a network of support, if not from the African American community, but people in the white community as well, and I would not rule out Stephen Jacob’s family members as being part of that,” Haaf said.

Dinah died in 1809, and the town paid for a coffin and a burial. A March 6, 1809, notice in Spooner’s Vermont Journal, a weekly paper in Windsor, recorded her death as “In this town, Dinah, a woman of color.”

Dinah was likely buried in the cemetery at Old South Church, the only one in town at the time, but Haaf has not been able to find exactly where.

“She would almost assuredly be in that cemetery, in the pauper’s section is my speculation, near the back,” he said, adding that at the time of her burial a small marker of some sort was likely put in place, but it would have rotted away.

“Let’s think of Dinah as a part of the Windsor community, a woman who wanted to claim this as a place of residence,” Whitfield said in response to a question at the end of his 2019 talk. “A person who played a role in what this town became. She worked, she took care of children. ... She’s part of it.”

Jacob died in 1817 at age 61, having long been absent from public life. After the Supreme Court case, he wasn’t re-elected to the bench.

He had always struggled with debt and around 70 creditors made claims against his estate. His land in Windsor was broken up. Haaf’s house sits on the first lot subdivided from Jacob’s land. In the cemetery, there are elaborate gravemarkers for Jacob and his family members, and there’s a street named for him.

Jacob Street, and what’s now called Jacob House, are now up for debate.

In the house, there were two finished rooms in the attic, said Judy Hayward, executive director of Historic Windsor, a historic preservation nonprofit that purchased the house in January 2009. “We think that’s possibly where Dinah lived,” she said.

Historic Windsor has put work into stabilizing the house, and has been trying to find new uses for it. It needs all new systems, and further stabilization, Hayward noted, work that would cost around $1 million. It’s possible Historic Windsor will issue a request for proposals.

Hayward acknowledged that some residents would like to rename the house. “It’s a challenge, because historically we’ve always referred to properties by the name of their first owner,” she said. “In doing so, we sort of perpetuate Jacob’s memory and we forget Dinah’s.”

The group’s board plans to keep the Jacob name on the house, Hayward said.

“You have to tell the truth, warts and all,” she said.

The planned state historic marker telling Dinah’s story will help put the building’s history in context.

A majority of Selectboard members voiced support on June 30 for changing the name of Jacob Street.

“Who we honor reflects directly on what we honor,” Smith, the board member, said in the meeting. “The name Jacob Street is honoring a slaveholder, and this is not consistent with our values.”

Board member Paul Belaski sounded a note of caution: “There are significant ramifications for changing a street name,” he said. State databases for tax and other purposes and for emergency services would have to be changed to make sure residents don’t lose services. Even so, “I think it’s a worthwhile discussion,” he said.

Continued discussion about Jacob Street is on the agenda for the Selectboard’s meeting at 7 p.m. Tuesday, held via Zoom.

For his part, Haaf continues to research Dinah Mason. He’s been to archives around New England and has looked up and cold-called descendants of the people involved in search of that elusive trove of original documents that might shed light on Dinah’s life. So far, such letters and diaries have not emerged.

He’s also written a book, a fictionalized account of events in which he can fill in details that fit in with his 12 years of research but might not be supported by documentation.

The life of Dinah Mason, even seen dimly, has the power to shake Vermont to its foundation.

“Here we are in liberal Vermont, in my opinion the first entity to ban slavery,” Haaf said. And yet Dinah Mason, among others, including that 8-year-old boy, were sold to Vermonters even as that noble sentiment was enshrined in the constitution.

“It happened here because people ignore laws,” Haaf said.

More than two centuries later, what Windsor residents choose to ignore, or pay attention to, is still in question.

Liz Sauchelli can be reached at esauchelli@vnews.com or 603-727-3221. Alex Hanson can be reached at ahanson@vnews.com or 603-727-3207.

]]>

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination