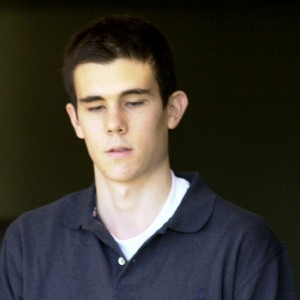

Thetford 21-year-old with cerebral palsy yearns for independence with a bit of support

| Published: 01-06-2023 7:35 PM |

THETFORD — In some ways, Owen Dybvig is just like any other 21-year-old still living at home: He’s ready to move out from under his parents’ wings and pursue his own interests, make new friends, and see more of the world.

But moving is a lot more difficult for Dybvig than it is for others his age because he has cerebral palsy, a brain disorder that inhibits muscle coordination, and in his case prevents him from being able to walk or speak. Over the past year, his family has struggled to find him an at-home caregiver to help him with the daily tasks he can’t do himself, such as changing his clothes, going to the bathroom or eating.

He splits time between the Thetford home of his father, former U.S. Olympic skier Evan Dybvig, and with his mother, Sarah Ireland. But because they’ve had no luck in finding an at-home aide, Owen has had to accompany his father to various construction sites around Vermont since this past summer for his work with Geobarns, a Hartford-based construction firm that specializes in “post-and-beam” building construction.

Though Owen Dybvig relies on a wheelchair, he and his father both point out he’s not intellectually hampered in any way; he processes conversations and understands people talking normally and can communicate capably. It just takes him a while to answer questions or respond because he needs to use an iPad attached to his wheelchair to do so.

While his dad and crew work, Dybvig is usually in a backroom doing his own thing — watching movies, surfing the internet or working on his blog. He had to get accustomed to waking up early and to the loud sounds made by the saws, drills and other machinery used on the work site everyday.

He’d rather be spending his time on something more productive, such as taking college classes online. He said he wants to learn more about web design and blogging.

“I am 21 years old,” Dybvig said in an email. “Most young people my age are going off to college and are living a life away from their parents.”

The Dybvigs’ experience is unfortunately not unique in the Twin States.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

Through new school partnerships, CRREL seeks to educate young scientists

Through new school partnerships, CRREL seeks to educate young scientists

Angela Smith-Dieng, director of the Adult Services Division of the Vermont Department of Disabilities, Aging and Independent Living, said that Vermont’s nine home health agencies, which are tasked by the state with providing personal care services and home and hospice care to Vermont residents, are experiencing significant hiring problems.

“The workforce shortage isn’t just in this program but really is across health care, home- and community-based services and our mental health agencies as well,” Smith-Dieng said. “It’s really systemic.”

Smith-Dieng’s department served roughly 2,800 people in at-home settings in 2022, she said, and that that group is receiving only about 85% of the services for which they’re eligible.

She said the shortage is a result of a combination of a few factors.

For one, Vermont has one of the oldest populations in the United States and is rapidly getting older, which means more and more people are aging out of the workforce and are not being replaced at a sustainable rate. New Hampshire isn’t far behind Vermont in this metric, nor is Maine. Additionally, Smith-Dieng doesn’t believe hospice or at-home caregiving is a field of work particularly appreciated by American society, and it’s difficult work to boot.

“It can be both physically challenging and emotionally challenging for the worker to do this kind of work, so it’s difficult for these jobs to be competitive when other types of jobs out there, like retail, (offer) similar pay rates,” Smith-Dieng said.

Those problems with hiring are having real-world impact on patients.

Ireland said her son Owen’s predicament is the result of a “distinct lack of respect of caregivers and their service.”

After shuffling through several candidates who were, in Evan Dybvig’s words, “total flakes” who promised a lot but were completely unreliable, he said he’s basically given up trying to find an at-home aide to help his son.

“I burned through my budget with flakes who (promised) this or that but nothing went anywhere,” Evan Dybvig said.

He’s also frustrated because he believes there are enough Vermonters looking for work for there to be someone out there reliable enough and open to working with his son. The wages he’s offering, which he said are around $25 per hour, should’ve been more enticing, too.

“He doesn’t need nursing care, just someone to help him with his (computer devices) and help him eat right,” Dybvig said. “Sure, familiarity with a wheelchair transfer and being comfortable with helping him go to the toilet takes a certain kind of person who’s OK with that, but they don’t need high-level training.”

Sylvia Dow, founder and executive director of Visions for Creative Housing Solutions LLC, an Upper Valley-based nonprofit that works to find permanent housing and lifelong support for disabled adults and has locations in Enfield and Lebanon, said it’s a big undertaking trying to find the right people to work in the field of at-home care. Since both facilities are New Hampshire-certified for residential care, rules and regulations, employee training and equipment are all held to a higher standard than what a parent or guardian might ask of an aide they’re looking to hire.

“We have a very clear program for how we onboard staff,” Dow said. “It makes it easier for us to find staff.”

Between the Enfield and Lebanon facilities, Dow said Visions takes care of about 22 people with various physical and cognitive disabilities, with plans to host 12 more people when they open a new facility in Hanover next year. But it’s just a drop in the bucket.

“We’ve turned people away from Florida to California, Arizona, Nevada,” Dow said. “It just seems so devastating to me (because) I talk to families from all over New Hampshire, from the Upper Valley, and so many of them say to me, ‘We’re doing it ourselves at home but it’s not enough.’ ”

Evan Dybvig said his son is one of about 40 people on a waiting list for a spot at one of Visions’ homes.

Through Vermont’s Choices for Care program, Owen Dybvig, who qualifies for long-term care Medicaid, has a few options for how he can receive aid and services from the state, including at home, at an enhanced-residential care facility or at an “Adult Family Care” home. AFC homes are owned and lived in by the home provider, who offers 24/7 care and support for individuals in a “family-setting.”

Owen Dybvig graduated from Thetford Academy in 2021, and moved into an “Adult Family Care” home shortly after, but Evan said it wasn’t a good fit and he was basically kicked out, which forced the family to initially move him into Grace Cottage Hospital in Townshend, Vt., before moving him back home last December.

A year has passed and they still haven’t found another AFC home that can take Owen. He’s still heading out most days with his dad to work sites.

Since the growing season ended just before Thanksgiving, Ireland, who is a gardener, has served as her son’s personal care attendant through the Vermont Department of Health, which has enabled her to forgo getting a part-time job and spend more time with him out in the community. A COVID-19 pandemic-era assistance waiver allowed her and Evan Dybvig to be paid as caregivers, but the waiver is set to expire on Jan. 11, Ireland said.

For most of the past few months, Dybvig has been watching and hanging out as his dad helps to rebuild the Meriden Library.

“He’s been pretty good-natured about it all, but I know he’s frustrated, too,” Evan Dybvig said.

Besides helping out with basic needs, there’s one other criterion that Owen hopes his future caregiver will have: an appreciation for the lighter side.

“The aides I liked the best had a good sense of humor because taking care of me can be funny,” Owen said. “It is important that I have a sense of humor about personal care because sometimes personal care gets very personal!”

Ray Couture can be reached at 1994rbc@gmail.com.