The rise and fall of Vermont, the most European state in the Union

| Published: 03-09-2019 10:30 PM |

When we say Vermont is the most European state in the Union, we don’t mean it’s the whitest in terms of ancestry — though it vies with nearby Maine for that distinction.

In terms of population trends, Vermont more closely resembles our friends across the Atlantic than it does most U.S. states. More people die in Vermont than are born there, a phenomenon with little precedent in the United States. And since at least 2010, Vermont hasn’t attracted enough immigrants from abroad to offset the residents it is losing to other states.

Vermont ranks so well on measures of childhood health and well-being that a Washington Post colleague once referred to it as “the best state in America.” But the 2020 Census will probably confirm that Vermont peaked during this decade and is now losing population, according to projections from demographer Shonel Sen and her colleagues at the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center.

Vermont is expected to lose people steadily until at least 2040, the most distant year the demographers dared predict. Vermont, Illinois and West Virginia are the only states that won’t hit new populations high over that time, according to the forecasts.

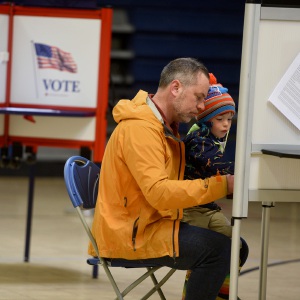

Children under 15 make up a smaller share of the population in Vermont than in any other state (although the percentage in Washington, D.C., is even smaller). On the other end, it trails only Maine for the share of population 40 or older. By 2030, more than 1 in 4 Vermont residents is expected to be 65 or older, according to Sen’s projections. The estimates are derived from a detailed analysis of five-year age groups in the past three decennial censuses, as well as the Census Bureau’s 2017 population estimates.

As a result, Vermont’s population pyramid closely resembles that of a Western European country.

It could be said the state’s politics have a Western European flavor as well. Former Burlington mayor and self-proclaimed democratic socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders has represented the state in Congress since 1991.

Sanders has often praised European policies. “We should look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway, and learn from what they have accomplished for their working people,” he said in a 2015 Democratic presidential candidates’ debate.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Hartford voters approve school budget and building repair bond

Hartford voters approve school budget and building repair bond

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

A top-heavy population pyramid is half the story. It shows fewer women of childbearing age, but it doesn’t tell us whether those women are bearing children.

It turns out they aren’t. Vermont had the second-lowest fertility rate, or births per eligible woman, in the country from 2013 to 2017, the most recent available Census Bureau figures show.

Vermont also has a highly educated population of adult women. About 39 percent of women 25 or older have a bachelor’s degree, compared with 34 percent of men. Only Massachusetts, Colorado and Maryland rate higher.

And higher education correlates with lower fertility. Separate Census Bureau figures show that, as of 2016, fertility among women between the ages of 15 and 44 with no more than a high school diploma is about 1.4 times higher than among women with a bachelor’s degree.

Non-Hispanic white women tend to have some of the lowest fertility rates of any group, data show, and about 93 percent of Vermont’s population identifies as non-Hispanic white.

Other New England states aren’t far behind in the low-fertility sweepstakes. But they have something Vermont doesn’t: migration.

From 2010 to 2018, Vermont attracted just 8,548 international immigrants, fewer than all but three states. A net total of 10,114 residents left for other states over that time. Maine, which faces many of the same demographic struggles, has been kept afloat by immigration. It gained 18,302 people from the United States and internationally from 2010 to 2018.

It wasn’t always this way. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Vermont grew faster than most states amid booming interest in rural life.

In the 1970s, University of New Hampshire demographer Kenneth Johnson said, “A dramatic and surprising shift occurred when more people moved to rural areas.” For the first time in a century and a half, rural America grew faster than the nation’s cities.

But for many Americans, the glow has worn off. In 2001, a Gallup poll found that 35 percent of Americans would prefer living in a rural area over towns, suburbs and cities. By 2018, that had fallen to 27 percent.

“Back in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s, people kind of liked the idea of living in rural areas,” said Art Woolf, an economist at the University of Vermont. “There was a cachet about it.”

But “in the last 20 years that has completely reversed,” said Woolf, who was Vermont’s state economist between 1988 to 1991. “And now people want to live in metropolitan areas.”

The state lacks the cities and transportation and other resources that have helped its neighbors weather the demographic storm.

Burlington, Vermont’s biggest city, has a population of about 42,000 people. When you compare each state’s largest city, it’s easily the smallest.

The state has faced population challenges before. Vermont’s growth stalled between about 1840 and 1960, when the country expanded and the state’s farmers decamped the Green Mountains for greener pastures.

“Why would you want to farm in Vermont when there’s Ohio? It’s a terrible place to farm,” Woolf said. “You’ve got a short growing season, rocks and mountains.”

But the state’s long struggle for population growth can be read as a hopeful sign. We could have written a similarly gloomy piece about the state in the ’40s or ’50s, as the demographic trends of the day seemed stacked against Vermont — and the 1970s-era boom would have proved us spectacularly wrong.

“One of the things about economic forces at work is they tend to be somewhat self-correcting,” said Iowa State economist Joshua Rosenbloom, who has studied New England’s economic history. “As population moves out, real estate prices fall and things that were uneconomical become economical.”

The self-correction isn’t guaranteed. Many farming-dependent counties in the Great Plains are entering their second century of decline. But Vermont’s natural amenities and recreation opportunities give it an advantage that other rural areas might not enjoy, Johnson said.

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’ Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth