Climate change poses threat to region’s brook trout

| Published: 05-29-2023 5:39 PM |

THETFORD — As anglers cast about Upper Valley’s streams and rivers this spring, Thetford Academy seventh graders had some brook trout to unload last week.

About 30 students gathered along the Ompompanoosuc River at the base of the Union Village Dam on Thursday, preparing to release the small trout, called fingerlings, they’d helped bring into the world.

The Thetford students started with about 100 eggs, and around 60 hatched. In the wild, only about two of that batch would have made it, Dan “Rudi” Ruddell told the students.

Ruddell is a watershed scientist with the White River Partnership, an environmental nonprofit that coordinated the trout program with Upper Valley schools. The effort is part of Trout in the Classroom, an environmental education curriculum circulated by national nonprofit Trout Unlimited, meant to connect students back to the waterways in their community.

In January, the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department dropped off a bundle of eggs that were cultivated at the Roxbury (Vt.) Fish Culture Station — the oldest brook and rainbow trout hatchery in the state. Students then raised the trout from eggs to fingerlings in an aquarium during the year, waiting for warmer weather so they could finish the job.

The seventh graders broke into groups to test water quality, assess surrounding habitat and examine aquatic life already in the streams at the base of the dam to find out the ideal location for their trout to begin their lives in the wild. Students from other schools, including South Royalton Elementary, the First Branch Unified Middle School in Chelsea and the Waits River Valley School in Corinth, have done the same this spring.

Ruddell knows the area’s rivers — and the teeming life within them — well. The past few years haven’t been business as usual for the aquatic animal kingdom, he said.

“When we talk about healthy streams, what are we judging healthy on?” Ruddell asked the students.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

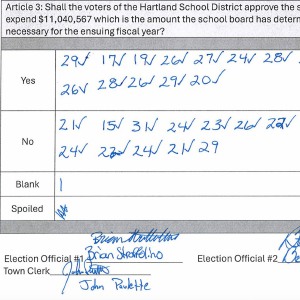

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

He emphasized the impact that watersheds, or the area of land that channels rainfall and snowmelt into streams, have on water quality.

Downstream doesn’t exist in isolation. “What we do upstream matters,” Ruddell said. That’s true of both land use and other human activity that drives forces like climate change, which is also impacting trout.

In the fall, the hatchery in Roxbury used water from the Third Branch of the White River to keep the eggs at cool temperatures to foster stable growth, but they still matured quickly. The eggs were the biggest Ruddell had ever seen, he said. Some hatched before they’d even made it to Thetford Academy.

Rising temperatures due to climate change are stressing the trout population, which prefers colder water. Trout are notably declining in the southern part of their native range in the eastern U.S., and there’s concern that the New England population could be similarly threatened in the future. But according to the most recent study by the state — done in 2017 — the Vermont stock is holding strong.

Still, two successive drought-stricken summers, with hot days drawing down water levels, have taken their toll on the state’s trout, Ruddell said. ”The last couple years, the water’s been so hot we’ve had trout swimming up to people and they can pick them up with their bare hands.”

Students gathered stoneflies, water pennies and dragonfly nymphs in canvas bags, called kick nets, from the main stem of the Ompompanoosuc, counting up the water bugs that make up a brook trout’s diet to make sure their own stock dines well.

“We want to keep track of this stuff over time,” Ruddell said. “If we were to come back and there were no insects, we’d know something was going on with the stream.”

The group snagged a rare albino stonefly. A student quickly named it Bob.

The seventh graders had spent their time in the classroom learning about the ideal river conditions for trout. Ruth Brooks, 13, had no problem with the assignment over the course of the year.

“We had to make sure their tanks were good, their water was good,” she said. “It wasn’t that bad.”

After analyzing the degree of acidity and nitrous oxide levels of a few sites, the group decided that Avery Brook, a tributary of the Ompompanoosuc with low acidity and chemical presence, would be the most accommodating release spot. Avery Brook is also very accommodating for skipping rocks, a few students proved.

“These fish are delicate,” said Sam Hecklau, the students’ science teacher, scooping trout the size of a pinky finger from a cooler into the buckets that the seventh graders used to ferry them down to the brook. He urged them to be gentle with the juvenile trout, who have just crested over the “fry” stage, when they’re generally less than one inch long and have learned to hunt for food themselves.

“They started out like larvae, and now they’re moving around like normal,” 13-year-old David Mitchell said.

The best release points in the brook would be behind a boulder or log, where the water’s a bit slower but they can get into the current “when they’re ready,” said Ruddell, the brook trouts’ final shepherd.

Frances Mize is a Report for America corps member. She can be reached at fmize@vnews.com or 603-727-3242.

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project