Latest News

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Local Roundup: Rivendell extends baseball win streak

Local Roundup: Rivendell extends baseball win streak

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — The Vermont Center for Ecostudies is looking for people who are willing to allow researchers to study their lawns as part of the Upper Valley Backyard Tick Project.Jason Hill, a quantitative ecologist at the White River...

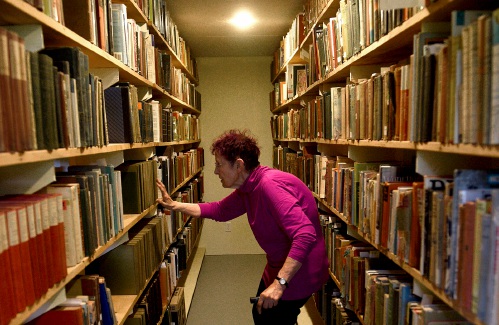

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

NEWPORT — Tucked in the basement of Newport’s Epiphany Episcopal Church, Micah Studios is a newcomer to the Upper Valley’s alternative education landscape.Founded in the fall of 2023 by two educators disillusioned with the town’s public school system,...

Most Read

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Editors Picks

Apply to join the Valley News Reader Advisory Board

Apply to join the Valley News Reader Advisory Board

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Sports

2024 Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse guide

Two words best describe Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse: quality and consistency.All four squads made the playoffs last spring. While none came home with a state title, Hanover and Woodstock made their finals, with the Wasps’ trip coming at...

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Opinion

A Yankee Notebook: An inevitable and terminal move

Living three and a half hours apart, as we do, my dear friend Bea and I get to see each other about every two weeks or so, on average. This is almost without doubt an ideal arrangement, as our lifestyles are quite different, and neither of us could...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Preserving habitat in Etna

Pitching in

Pitching in

Picture day prep

Picture day prep

Helping a good cause in Etna

Helping a good cause in Etna

Spring cleaning

Spring cleaning

Arts & Life

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

For much of its history, JAG Productions, the small, White River Junction theater company that specializes in telling stories from deep inside the black, queer, American experience, has had to be nimble. Company founder Jarvis Antonio Green has...

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Obituaries

Terrance W. Hood Sr.

Terrance W. Hood Sr.

Enfield, NH - Terrance W. Hood Sr., 63, passed away unexpectedly Saturday April 6, 2024 at Dartmouth Health. He was born in Barre City, VT and was raised by Arthur & Marjorie (Salomaa) Hood... remainder of obit for Terrance W. Hood Sr.

Veronica Alonzo

Veronica Alonzo

Lebanon, NH - Veronica Ann Alonzo died peacefully at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center on April 10, 2024, in Lebanon NH at the age of 63. Veronica was born on May 6, 1960, in Orange, Calif... remainder of obit for Veronica Alonzo

Elizabeth Allebach

Elizabeth Allebach

Hanover, NH - Elizabeth "Betty" Belle Peach Allebach, 91, beloved family member and friend to many, died peacefully at Kendal of Hanover on April 7, 2024. She was surrounded by many relativ... remainder of obit for Elizabeth Allebach

Marion D. Barr

Marion D. Barr

Weathersfield, VT - Marion D. Barr, age 88, passed Sunday, March 10, 2024. A service will be held at 10am on Saturday, April 27, 2024, at the Brownsville Community Church. Knight Funera... remainder of obit for Marion D. Barr

Woodstock Aqueduct Company seeks to double water rates

Woodstock Aqueduct Company seeks to double water rates

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show