Newport Manufacturer and Its Owner Still Going Strong After More Than 55 Years

| Published: 09-24-2018 9:44 AM |

Newport

The blade inside the 40-drum-capacity tank, dubbed “The Monster,” is turned by a 60-horsepower motor that mixes batches of industrial coatings that Malool sells to packaging companies around the world under his company’s name, Roymal Inc.

“This is where we make everything,” Malool said about the spotlessly clean factory room fitted out with 25 stainless steel and fiberglass tanks ranging up to 6,000 gallons. Inside, the tanks are milky white solutions that eventually become the invisible coatings on everything from fast-food wrappers to flame-retardant clothing for Barbie dolls.

Industrial coatings are a necessary if uncelebrated component of consumer packaging. Composed of polymers, they act as protective barriers on the inside of a paper cup to prevent the hot coffee from seeping through and turning the cup into soggy pulp, or the grease in an order of fast-food French fries from penetrating the sleeve and making an oily mess of anything it comes into contact with. They also can act as clear membranes to prevent labeling from being scratched in shipping, or block microbes from entering food contents inside the bag of frozen peas.

Malool is 91 years old — he’ll be 92 next month — and still goes into work most days of the week at the company he founded out of his house in 1962. He totes his belongings to the office in a red plastic supermarket shopping basket.

With the exception of gunmaker Sturm, Ruger, Roymal is one of the few industrial manufacturers remaining in Newport, a town that once boasted three woolen mills and three shoe factories. He’s spurned countless offers from bigger outfits to buy Roymal.

“You know what they would do?” Malool said of the feelers he has received from other companies, flashing a sign of irritation. “They’d take over and then spit us out. I don’t want that to happen. I don’t want us to leave Newport.”

Malool is fiercely loyal to the town.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Twenty years ago, he formed the Roy M. Malool Family Foundation, which has given tens of thousands of dollars to such organizations as Newport Historical Society, Newport Opera House, Newport Police Department, Richards Free Library and Newport Food Pantry, among others.

Legally blind, Malool wears goggle-like yellow-tinted eyeglasses and can get around fine, walking nimbly with a cane and opening doors himself and negotiating steps without the slightest assistance.

“I like to work,” he says. “I’m Armenian.”

Traveling Salesman

Malool grew up in New Jersey, the son of immigrants. His father worked for an industrial coatings company. Malool was rejected for enlistment in the Navy because he was color blind, so he spent World War II working in the steward’s department of U.S. merchant ships.

After the war, it was natural for Malool to follow his father into the industry, and he started out as a traveling salesman selling industrial coatings to companies such as General Electric

“That lasted to 1956 when I said, ‘To hell with it, I got to be on my own,’ ” Malool said.

His family vacationed in Lempster, N.H., when he was growing up, and Malool said he always liked northern New England — it had become his sales territory — so he settled in the area.

Initially, Malool worked as a broker, matching manufacturers of industrial coatings with customers who needed specific formulations, before going into the manufacturing end himself in 1964.

There are only a handful of companies in the U.S. that do what Malool’s Roymal does: manufacture water-based industrial coatings that are applied on a host of packaging materials to keep their integrity intact for handling and safe for consumers to use.

The business is about as unglamorous as manufacturing gets, yet it has proved remarkably stable as technology and global economic forces resulted in the town’s once proud factories moving operations overseas or shutting down.

“We’ve stayed right here in Newport,” Malool said with evident self-satisfaction. “I like being small and specialized so it shows up on the bottom line. I love the bottom line.”

With a pate as shiny as Mr. Clean’s and a disarming avuncular, toothy grin, Malool is far more worldly than being the owner of a small town manufacturing business would suggest. Until he began cutting back on travel a few years ago, he would spend up to six months every year traveling around the country and abroad — he estimates he’s been to more than 35 countries.

A few months ago he was in Mexico; a trip to Germany is coming up.

Twice he married Finnish women, both whom he met on business trips to Finland. After Malool’s first wife passed away, he met a Finnish law enforcement officer several years later at the airport. They married and the couple lives in Newport.

Pivotal Decision

Roymal’s specialty is water-based coating technology, which it developed in 1968 in a move away from solvent-based coatings as oil prices became more volatile and concerns grew about the petrochemical products’ impact on the environment.

The term “water-based” refers to the solution — water — in which the resin binders that form the barrier coating are dissolved. Traditionally, the packaging industry had used “solvent-based” solutions, a byproduct of oil, to dissolve the binders. Although solvent-based coatings are considered safe, they release potentially harmful vapors during the drying process and the packaging industry is moving away from using them.

“It was the smartest decision I’ve ever made,” he said. Water-based industrial coatings soon became widely adopted throughout the packaging industry, allowing the tiny Newport company to become a leader in the field.

Malool’s customers are “conversion” companies that make packaging materials on behalf of consumer product companies. A cabinet in his company’s conference room displays familiar household names of companies that use Roymal’s coatings on their packaging: Corona Beer boxes, Colgate toothpaste cartons, McDonald’s pie sleeves, Kingsford Charcoal bags, Ben & Jerry’s ice cream cartons, pet food bags, wrapping paper and Asian brand cigarette packs.

Industrial coatings are the kind of prosaic product that people are not aware of, but that everyone comes into contact routinely. Technology can make whole industries obsolete, while changing consumer habits and tastes can wipe out a brand almost overnight. But the need to coat packaging materials is eternal, Malool explains.

“People are going to eat. People are going to smoke. People are going to drink,” he said. “And all that packaging needs to be printed and coated.”

The clear industrial coatings are applied as a micron-thin layer on packaging material — typically paper or thin plastic film — via a rotogravure or flexographic printing machine. The “conversion” companies then send the packaging materials to the end user, typically a consumer product company.

Positioning for the Future

Roymal employs 15 people and has an on-site laboratory headed by technical director and chemist Michael Frost, a 15-year company veteran and University of New Hampshire graduate. Laura Stocker, who joined Roymal 40 years ago right out of Colby-Sawyer College with a business degree, is president (Malool’s title is chairman).

Malool says that Roymal has formulated literally “hundreds upon hundreds” of different coatings for customers over its more than five decades in business. Even a coating for same packaging might require a different formulation, depending on such factors as the heat or humidity in the region where the product is sold.

The base material for coatings is polymers, which Roymal buys from chemical giants such as BF Goodrich and Dow and arrives by truck at Roymal’s nondescript plant on Route 11 outside of downtown Newport and is pumped into the bulk tanks.

At the plant, resins and binders such as urethanes, acrylics, alkyds and epoxies are added to the base polymer — in a formulation that was previously developed in the lab — to make the coating. The additives account for 2 percent to 3 percent of the chemical composition of the coating. After mixing, the formulation is then transferred into 55-gallon drums, the drums strapped to palettes, and shipped to packaging plants in the U.S. and abroad.

Malool declined to give a figure for Roymal’s total revenues, but a single drum filled with industrial coating can sell for between $2,000 to $5,000 each, depending on the formulation. He said he doesn’t tabulate how many drums the company ships annually “because that’s not the way I look at it.”

Malool has two daughters, but neither are involved in the business. He said that Stocker and Frost are positioned to buy the company from him, and he wants to sell it to them.

“We’re working on it,” Malool said, not offering a timeline about when that would happen.

John Lippman can be reached at jlippman@vnews.com.

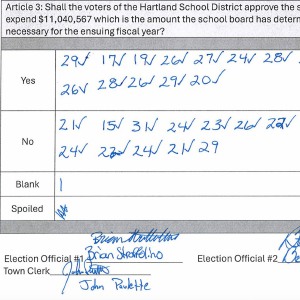

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote