Art Notes: The complexity of simplicity in Lois Dodd retrospective

| Published: 09-08-2022 6:37 PM |

A phrase I’ve often heard in reference to Lois Dodd’s work is “deceptively simple.” In fact, there it is, right at the beginning of the wall text for “Natural Order,” a retrospective of Dodd’s work at the Hall Art Foundation in Reading, Vt. Deceptively simple.

What is it about Dodd’s work that suggests simplicity, and what qualities does her work possess, upon closer inspection, that reveal the deception? Part of it, I think, has to do with the way the work is reproduced. It just looks so good in photographs. Dodd’s work is highly photogenic and looks crisp and fresh in print, on social media and, yes, in person.

Dodd was born in 1927 in Montclair, N.J., and studied art at the Cooper Union in New York City in the late 1940s. Though she didn’t initially set out to be a painter, she was swept up in the artistic ferment of the downtown art scene and became a founding member of the cooperative Tanager Gallery. Since that time, she has maintained residences in New Jersey, Maine and New York City, and has used these locales as settings for her unique brand of acutely observed perceptual paintings.

Yellow Cow (1958) is the earliest work on view, and it demonstrates Dodd’s early endeavors at painting rural naturalism even while she was at the center of the maelstrom that was midcentury abstraction. The bulbous chrome-yellow cow and the flattened planes of the pasture behind it are fused into an interlocking cluster of geometric forms that push the boundaries of abstraction and figuration.

In the early 1970s, Dodd began a series of studio interiors in her loft on New York City’s Lower East Side. Night Sky Loft (1973) is a prime example. An old cast iron radiator creates a striated pattern that leads the eye to a large, oval mirror in which an ornate chair is reflected. Slivers of light from the adjacent building are visible through the inky studio window. Here, as in much of Dodd’s work, the seeming banality of everyday life becomes a rich visual experience, one charged with feeling as it is filtered through her field of vision.

About half of the 50 paintings in the exhibition are on loan from other collections and the other half are from the Hall’s collection. The exhibition is expansive without being overwhelming. The scale of the galleries is intimate and accommodate the relatively modest sizes of Dodd’s canvases well. A viewer gets to experience them closely in rooms that are scaled to everyday life.

Dodd’s work is rooted in tradition while at the same time reaching beyond tradition into the realm of the contemporary. She seems to frame her images as one sees them, rather than thinking about composing an image for the paintings. She frames and paints the scene according to her exact position in relation to her own field of vision.

Natural Order (1978), the painting from which the exhibition’s title comes, is a scene of the woods near Dodd’s home in Maine shortly after a storm knocked some old-growth pines down. The painting is broken up into intersecting planes of light and shadow, lending the scene a faceted appearance. Cezanne comes to mind, and Dodd certainly borrows cubist compositional strategies. Dodd captures the pure feeling of standing in the middle of the woods, and you can almost hear the gentle crunch of the pine needles underfoot.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

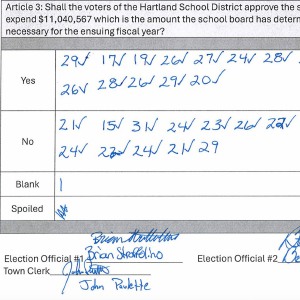

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

By painting the scene as it is, without reaching for common pictorial tropes, Dodd immerses the viewer in the scene in a way that evades most representational painters. Her paintings are experiential as much as they are visual.

Another critical aspect of Dodd’s work is the relationship between speed and accuracy. Much of Dodd’s work is created in single sessions and with minimal editing. As a seasoned painter with a highly skilled eye and equally deft hand, she is able to calculate the colors and locations of her forms with a high degree of accuracy.

You get a good sense of this in works such as Tree Shadow on Snow (1995) where the snowbank, blue shadows and the dark brook that cuts through the scene are all delineated with a few economical strokes. Dodd doesn’t need to go back and correct, edit or otherwise fuss about the canvas: She gets in and out so that the image is clear and crisp while retaining its painterly vitality.

While Dodd’s work consists mainly of landscapes and interior scenes, the human figure makes an occasional cameo, though rarely in a straightforward or expected way. On occasion she draws from the model as part of a drawing group that meets near her home in Maine. From these sessions, the artist has created works that feature the female nude posed in the landscape. Step Ruin with Figure (1997-2001) depicts a standing female figure seen from the back and posed among the architectural remnants of a dilapidated house. A tall stairway twists upward as the verdant landscape is seen through the exposed door jamb. Dodd has elevated her subject and given it the presence of Greek classicism with the ruin and figure echoing the feeling of a statue in a temple.

Shadow with Easel (2010) is a delightful interpretation of a self-portrait. The work is one in a series of such images of the artist’s shadow as she paints at her easel. Her gesture and contour create an unmistakable presence of the artist at work. Dodd is the sort of painter whom artists deeply admire, because her work invites a degree of technical scrutiny, and the longer one looks, the more it reveals. Her work seems to beckon you to get closer and in so doing, leaves one with an even deeper admiration for her achievement.

Lois Dodd: Natural Order is on view at the Hall Art Foundation through Nov. 27. For more information visit www.hallartfoundation.org.

Eric Sutphin is a freelance writer. He lives in Plainfield.

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project