Norwich artist Penelope Bennett looks back, and ahead

| Published: 03-26-2019 3:12 PM |

P

During the German bombardment of London in World War II, Bennett’s mother urged her two young daughters to draw and paint to take their minds off the fear of wondering whether their house would be hit or whether their father, a volunteer firefighter, would be killed.

“She was keeping us busy while the bombs were flying,” Bennett said.

That sense of making art because of or despite the uncertainty and turmoil around her has carried Bennett through a peripatetic life, and grounds her in a period of some national anxiety about the direction of the country.

A retrospective of Bennett’s work is on view at Two Rivers Printmaking Studio in White River Junction through April. She has been mulling over the direction her life took since the war: from London to New York to Spain to Vermont. One culture is laid over an earlier culture which rests on the foundation of another. One by one, little by little, they have shaped her.

“I think I have benefited from three cultures,” she said in an interview this week at Two Rivers. Bennett, who doesn’t want to give her exact age but who was born just before the war, lives in Norwich with two cats and spends a great deal of time reading newspapers, she said.

Bennett is a slight figure with piercing dark eyes and a not easily tamed mass of black and gray curls. Although she has lived in the U.S. since the 1950s, she still has a discernible English accent, a certain crispness in speaking. Her stories loop around each other and unravel, like a ball of wool.

“I’m garrulous,” she said, with a glint in her eye.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

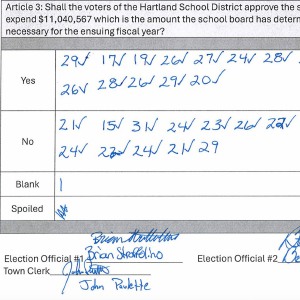

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

At Two Rivers, she was preparing a large linoleum plate for printing. She showed off a wooden rice spoon, bought decades ago in New York’s Chinatown, which she would use to press the paper onto the carving of Mary Magdalene. This is not your parish priest’s Mary Magdalene: she’s nude, on her back, with legs open. Her gaze is frank.

“I know she’s outrageous, but we women have to be now,” Bennett said, alluding to the #MeToo movement, and other expressions of protest against entrenched sexism.

Her subject matter is eclectic. Greek myth, the civil rights movement, Persian miniatures, portraits of Einstein, Freud and Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce and many prints in which she contemplates mortality.

There are echoes, perhaps, of William Blake in her mystical studies of humans toppling, metamorphosing, arms outstretched, joyous one minute and despairing the next. One print depicts the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, but with a twist. Adam is leaving for another planet because “we’ve mucked up this one. But I knew Eve would have children so she wouldn’t leave,” Bennett said.

On a print of Freud, Bennett etched his observation that “The tendency to aggression constitutes the most powerful obstacle to culture.” A print of Frederick Douglass includes his remark that “The limits of tyrants are proscribed by the endurance of those whom they suppress.”

Environmental concerns, and the unease we feel with the growth in online vitriol and the divisions in society, are subjects to which Bennett gives a great deal of thought. “What do you do when you’re living in a situation like that? How can one person have an effect?” Art is her way of working through such questions.

In a way, her childhood during the Blitz made some things quite clear. “We knew who the enemy was then and it was very obvious,” she said.

Her family, father William, mother Florence and sister Sally, emigrated in the 1950s from Britain to New York City. Her father was a “jolly, heavyset man” who worked in a chocolate factory after the war; he’d wanted to be an RAF pilot but was rejected because of three childhood bouts of rheumatic fever.

Her mother, the daughter of Cornwall farmers, was a “toughie,” with rippling arm muscles. She had taught her daughters how to use knives to stab any German paratrooper who might land on their suburban London home. Sally was, Bennett said, “a blonde English beauty” who was also interested in pursuing art. (She lives in the New York borough of Staten Island.)

They were not raised with any religion, although Bennett was baptized in the Church of England, and she and her sister went to Catholic school in England. Bennett’s mother was Protestant, and her father was Jewish. Culturally, Judaism was never discussed or brought into the house, Bennett recalled. She speculated that her mother disapproved. But Bennett recalled her father listening to a recording by the comedian and singer Mickey Katz, father of actor Joel Grey. Bennett’s father sang along with Katz in Yiddish.

“He would play this record again and again. My sister and I were ignorant of what this meant. He has this record player in our play room. Why is he driving us crazy playing this again and again? I’m sure he wanted us to appreciate it, but culturally we just didn’t understand,” Bennett said.

Bennett studied art at Hunter College and met her future husband, sculptor Roy Shifrin, when she was looking at a cheap apartment on the Lower East Side, where she could also make art. Shifrin was a friend of the prospective landlord.

“It was a very seedy apartment. But what wouldn’t one do for art?” she said. Although they are divorced (Shifrin lives in Wilder), they made a pact with each other and their children that they would still look out for each other as they got older.

She married at 23, and in 1964 she and Shifrin moved to Catalonia, in Spain, because they liked the idea of living less expensively while making art, and Shifrin knew there were foundries there using the lost-wax technique of casting bronze. They lived not far from the site of the Battle of the Ebro, the final conflict of the Spanish Civil War, and became close to a farming family there. Bennett made a study of them at the dinner table, their faces heavy and grave. She feels their seriousness was an echo of the brutality of the war and its lingering fissures, 30 years later.

While they lived in Spain, she and Shifrin had two children, a girl and boy, both now in their 40s. They were content to live there until, she said, they felt that their children were not getting an adequate education. After researching public schools on the East Coast, they decided to move to Norwich, where the children exchanged their Catalan for a Vermont accent, Bennett said.

Bennett has her work in the collection of the Royal Academy in London, and has exhibited at Dartmouth and the 92nd Street Y in New York, among others. She would like to do more painting but also considers whether she has enough time to give it serious attention.

“I don’t have enough years to really develop a painting style,” she said. She is preoccupied with another predominant concern of the artist. “Ideas come and you don’t know if you’re capable of doing them. Will I have done what I’m capable of?” she said. “To say the least, I’m a very late bloomer and I’ve been working all these years, but it’s only now that I feel that I’m in the groove.”

Penelope Bennett’s retrospective is on view at Two Rivers Printmaking Studio in White River Junction through April. Hours are 11 to 2, Tuesday through Friday, or by appointment. For information go to tworiversprintmaking.org or call 802-295-5901.

Nicola Smith can be reached at mail@nicolasmith.org.

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm