New EPA rule will require more of Vermont’s public drinking water systems to address PFAS

| Published: 04-14-2024 6:30 PM |

The federal Environmental Protection Agency issued a landmark rule on Wednesday that regulates the amount of PFAS, a harmful class of chemicals, in public drinking water for the first time.

Exposure to PFAS, or per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, has been linked to cancers, liver and heart problems, and immune and developmental damage to infants and children, according to the EPA.

In Vermont, the state’s Agency of Natural Resources has been regulating PFAS in public drinking water systems since 2019. The process began after state officials discovered high levels of the substance in private drinking wells in the Bennington area.

Despite the existence of state regulations, Vermont will still need to adapt to the new federal rules.

Vermont’s statewide limit for PFAS in drinking water is 20 parts per trillion, higher than the new federal standard, which is 4 parts per trillion for the chemicals PFOA and PFOS and 10 parts per trillion of four other types of PFAS. State water quality standards must be equal to or stricter than federal standards.

Ben Montross, manager for the Department of Environmental Conservation’s public drinking water program, said about 20 public drinking water systems exceed the current state standard, including several that serve Vermont schools. An additional 30 systems would exceed the new federal standard.

A public drinking water system falls within the state and federal regulations if it serves the same people for six months or more in a non-residential setting — for example, schools, office buildings, factories — or if it’s a community or municipal system that serves at least 25 people or 15 connections in a residential setting.

PFAS can contaminate drinking water sources through, for example, nearby industrial activity or when a school or other facility has a private septic system and a private well and regularly use substances such as floor wax, floor cleaners or other chemicals.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

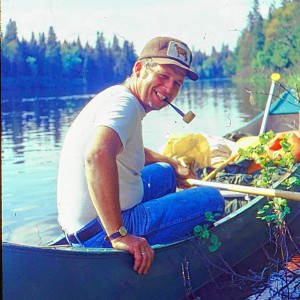

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

“That will go down the drain, and the drain is septic, and then that contaminates the well, and then it just kind of loops and perpetuates in that cycle,” Montross said.

Treatment systems that filter out PFAS are often expensive. The cost varies widely and depends on a number of factors, such as whether the drinking water system has a space to perform the treatment or whether an additional building with light and heat is required, according to Montross. The water may need to be pretreated to remove substances such as iron and manganese before PFAS can be removed.

“It really is site- and system-specific,” Montross said.

The EPA’s announcement of its new rule also pointed to a slew of federal funding that can be used to help communities address PFAS. The pots of money include $1 billion in new funding; $9 billion through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that has already been designated for drinking water impacted by PFAS and other emerging contaminants; and $12 billion, also through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, for general drinking water improvements, including PFAS.

Vermont will see between $8 million to $9 million of that money every year for the next five years, Montross said. Managers of public water systems can apply for grants through the Department of Environmental Conservation.

“We are also setting up a contract where we are hiring three engineering firms that will be doing the design for free for those water systems that need the help,” he added. “We are about to issue those contracts and then start gathering and soliciting the systems that need the help and then assigning an engineer to them at our expense using that grant money.”

There is also a forgivable loan program available to public drinking water systems that will have between $7 million and $8 million of funding available each year over the next five years, according to Montross.

The Vermont Department of Health is working to compile a list of resources for people with private wells who are concerned about PFAS contamination, he said.

The EPA gives states three years to collect data about PFAS in public drinking water systems and another two years to implement treatment systems.

Because Vermont has already been monitoring PFAS in public drinking water, the state has a head start, Montross said.

Even so, officials at the Agency of Natural Resources still have a lot of work to do before they understand exactly how the state’s existing regulations overlap with the new federal regulations, he said.

For example, there are thousands of types of PFAS, and the federal regulation applies to six of them. Vermont regulates five types of PFAS.

Last March, during an earlier stage of the process, the EPA was considering an even stricter proposal for regulating PFAS. The agency’s announcement on Wednesday calls the final regulation “achievable using a range of available technologies,” but it still sets a “maximum contaminant level goal,” a non-enforceable health-based goal, at zero for PFOA and PFOS.

“This reflects the latest science showing that there is no level of exposure to these contaminants without risk of health impacts, including certain cancers,” the announcement states.

Hayley Jones, Vermont and New Hampshire director of Slingshot, a regional advocacy organization that helps communities organize and fight the impacts of pollution, celebrated the new regulation on Wednesday. The group was active in Bennington when the news of PFAS contaminations arrived there, they said.

Jones said the news is “tangible” because “we haven’t had any enforceable federal standards that regulate PFAS and our public drinking water supply until this announcement,” and “symbolic because it’s showing that the federal government is really putting their weight behind all these community efforts to regulate and eradicate PFAS.”

“We’ve always called for zero,” they said, “because we know, and our leaders who have been exposed know, that there’s no safe level of exposure to this class of chemicals.

“So four parts per trillion is a great start, and we’ll call for it lower and lower.”

Big drop in tuition and aid is boosting Colby-Sawyer

Big drop in tuition and aid is boosting Colby-Sawyer  How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war

How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war