With a lack of state funding for education, NH property taxpayers bear the brunt of costs

| Published: 12-09-2023 12:26 AM |

The Allenstown school district spends five times more than the amount the state of New Hampshire gives to pay for an adequate education.

This lopsided equation relies heavily on local taxpayers to make up the difference to pay for everything from teacher salaries to school supplies.

If the district followed the state of New Hampshire’s funding formula, it would have to cut the majority of services offered to its 500 students.

Among the first things to go would be English Language Learner support, special education services and extracurricular clubs. Next, school resources: no supplies, building repairs or educational materials like new textbooks. And finally, personnel: two secretaries, three out of four custodians, the art, music, physical education and behavior teachers, one of two nurses, guidance counselors, the assistant principal and the superintendent (among many other positions) would be immediately fired.

Even with these cuts, the district would still be over budget. Allenstown wouldn’t have enough money to pay for its tuition agreement with Pembroke Academy, where students attend high school.

That means an adequate education in town would grind to a halt after the 8th grade.

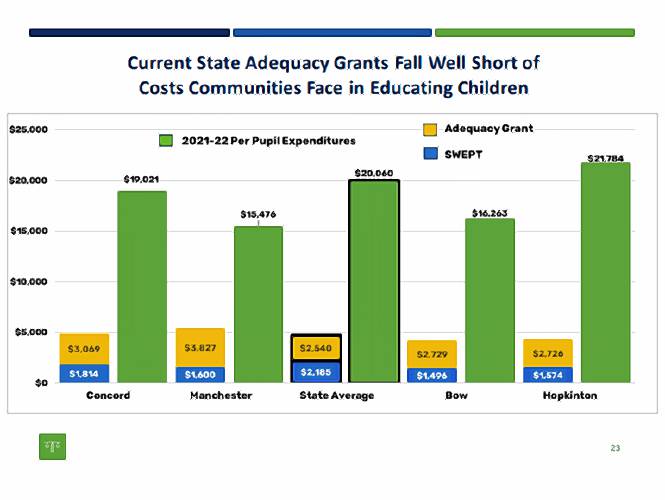

With a total budget of $12.2 million for the 2022-23 school year, the district spent just over $24,000 per pupil. The state gave the district $4,980 per student, or about $2.4 million.

The $20,000 difference is a stark example of the state education funding gap in New Hampshire, according to the NH School Funding Fairness Project, a nonprofit and advocacy group.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

“If you actually look at a budget, the state is in Never Never Land about what the grants can pay for and what they can’t,” John Tobin, one of the founders of the project, said at a presentation in Concord Tuesday night.

For decades, the state of New Hampshire has underfunded its school systems and relied on municipalities to make up the cost. At the same time, the state ranks among the highest for tax burden and the lowest for public education funding.

A matter of miles between zip codes translates to two vastly different tax rates to raise this money.

Yet state leaders are beginning to rethink education funding, as a result of a recent court ruling in the case ConVal v. the State of New Hampshire, where local school districts argued that current adequacy calculations were unconstitutional.

Eight miles apart in Concord, two houses are valued at the same amount, $450,000. One paid $6,500 in school property taxes in 2022. The other had a bill of over $8,000.

The difference was the alternate tax rates for schools in Concord at $14.63 and Merrimack Valley in Penacook at $17.87, a $3 difference.

It’s a common problem across the state. To raise money to fund the school system, communities that have lower property values have to set higher tax rates.

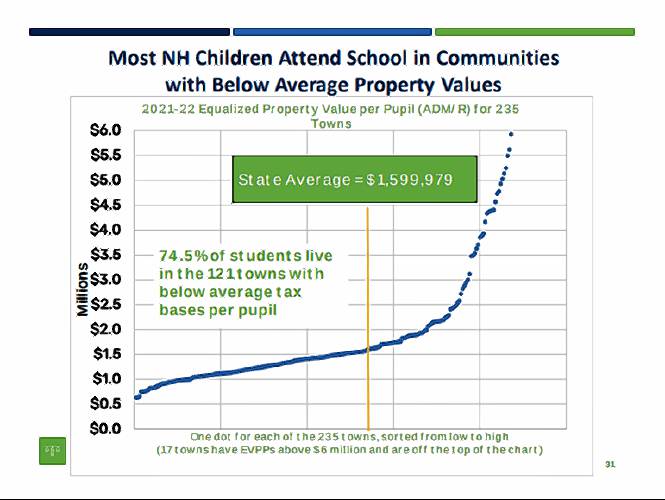

The reality is in New Hampshire 75% of students live in a town that has below-average property values, meaning they pay more to make up the difference.

“There is every sort demographic in New Hampshire, our biggest cities, our smallest towns, every single county, communities that are way on the left side of the political spectrum, some on the right, some in the middle,” said Zack Sheehan, the executive director of the funding fairness project. “So this is a problem that does not just affect a specific demographic, a specific party, a specific part of the state.”

This conundrum is the result of decades of legislative decisions following a court ruling from the 1990s, Claremont v. the State of New Hampshire, said Tobin, who was part of the legal team in the case.

In the Claremont ruling two major themes emerged: the state has a responsibility to provide a “constitutionally adequate education” for students and to do so, taxes should be raised at a uniform rate.

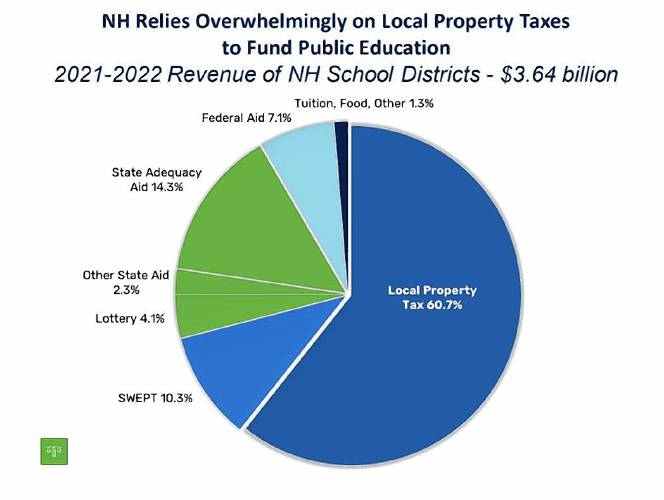

For that uniform rate, lawmakers introduced the Statewide Education Property Tax, commonly known as SWEPT. This tax contributes to about 10% of state education funding. But it still comes from the pockets of local taxpayers.

Despite an initial decrease in property tax rates in the aftermath of the Claremont decision, little has been done to offset the burden in years to follow, said Tobin. From 2012 to 2022, the cost of funding public education from the state increased by $47 million. For local taxpayers, it was 13 times that, at $614 million.

“The state has slipped backward and has allowed things to get worse,” said Tobin. “Over the last 10 years, the burden has continued to shift towards local property taxpayers… in order to fill the gap, all of us who own homes or businesses had to pay more in more local taxes.”

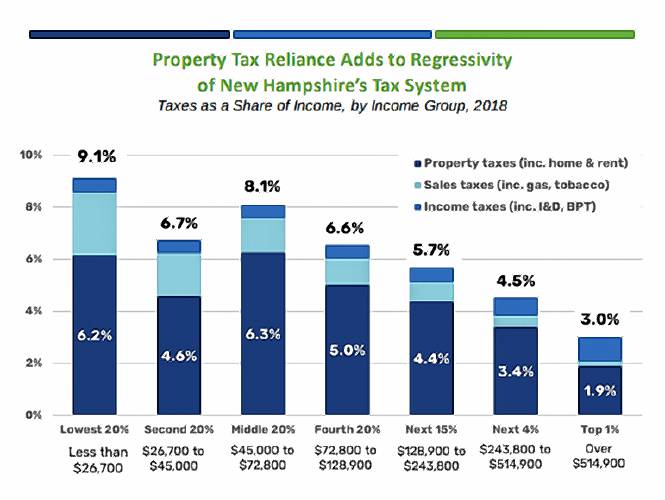

Property taxes in New Hampshire are also a near-perfect regression. The bottom 20% of earners, who make less than $26,700 a year, spend 9% of their income on taxes. For the top 1%, who make over $514,000, only 3% goes to taxes.

The reality of this system is that if a homeowner can afford a house in a town with higher property values, they’ll see a payoff with lower property taxes.

“What you see is that a lot is influenced by your ability to pay the entrance fee to get into a community that has low taxes,” said Sheehan.

Similar to the Claremont case, the Contoocook Valley School District challenged the state’s education funding formulas in a lawsuit in 2019. Last month, Judge David Ruoff, in Rockingham County Superior Court, presented a new number for base adequacy per student: $7,356 per pupil.

Current law sets that number at $4,100.

In his ruling, Ruoff paved the way for the legislature to rethink the state’s responsibility to fund public education in New Hampshire. But at a minimum, it must be at least nearly double, which would boost public education funding by half a billion dollars.

But it’s not a matter of spending more. Instead, it’s a shift in responsibility to the state.

“He’s not saying we need to spend another $537 million. We are spending that money now. You and I are spending that money in our property tax bills,” said Tobin. “The question is who pays that $537 million.”

But instead, the ruling dictates that there needs to be a shift in who is responsible for paying for education.

If the legislature adopts a base adequacy rate of $7,356, then the state portion of adequacy would shift from 14% of school funding to a quarter of the pie.

It would, in turn, alleviate pressure from local taxpayers, who would fund 58% of school spending, rather than 70%.

But the reality is that even Ruoff’s figure is conservative, said Tobin, and purposely so. In 2022, the actual cost per student was just over $21,000, according to the Department of Education.

But the ruling explicitly stated that the legislature should determine a new figure – $7,356 is to serve as the minimum threshold.

“The true cost is likely much higher than that,” Ruoff wrote in the decision.

A second case, Rand v. State of New Hampshire, again piggybacks on the Claremont decision. This time, local property owners are arguing that there is not a uniform rate to fund education, thanks to the reliance on their tax dollars.

Although, Ruoff has yet to issue a ruling on the Rand case, two injunction motions have already set a precedent for school funding changes. The first, is that the state’s method of allowing municipalities to retain excess SWEPT funding, rather than redistribute it to areas with lower property values, is unconstitutional.

There are 52 municipalities that retained $26 million in excess SWEPT, meaning they raised more than what was required by the state tax rate, according to the funding fairness project.

In previous years, for unincorporated towns that do not have a school district, the Department of Revenue Administration had set a negative tax for local education, so these communities could forgo funding state education. This impacted 19 cities and towns. Now, this practice is also unconstitutional.

Ahead of the legislative session in January, a number of bills will look to rethink education funding.

One piece of legislation proposes increasing the base adequacy $10,000 per student, which was argued in the ConVal lawsuit.

Another, one mirrors the Rand case, eliminating the ability to retain excess SWEPT and issue a negative education property tax rate.

Funding solutions could also come through other revenue sources, said Sheehan. Last year, lawmakers voted to accelerate the repeal of the interest and dividends tax, which will result in a loss of $135 million in revenue per year.

That money could cover the cost of universal school lunch for the state, increase base adequacy by $800 per student or provide school building aid funding, he said.

A bill sponsored by Rep. Mary Jane Wallner, a Concord Democrat, would reinstate the tax.

Other proposals focus on special education – with bills to mandate the state covers all special education costs and increase special education adequacy grants. Another one would start a commission to study special education funding.

Rep. David Luneau, a Hopkinton Democrat, has also introduced a bill to change adequacy, SWEPT and property tax relief, in line with findings from the Commission to Study School Funding recommendations.

Luneau chaired this commission, which released a report in 2020. The legislature has yet to address its findings.

These are all bills that could offer a solution to a problem that has continued to build over time, said Sheehan, especially on the heels of the ConVal ruling that mandates change to be dictated by the legislature.

“We are currently paying as local property taxpayers to support the public education system,” said Sheehan. “It’s unconstitutional and specifically the solution lies with state-level lawmakers.”