Jim Kenyon: Measuring the problem of homelessness in Lebanon

|

Published: 01-26-2024 10:00 PM

Modified: 01-31-2024 10:23 AM |

They trudged across fields blanketed with fresh snow to check out abandoned buildings. Under a cold drizzle, they stepped cautiously through parking lots coated with black ice in search of occupied vehicles. As day turned into night and winds picked up, they shined their flashlights inside dumpsters loaded with debris.

On Wednesday evening, a small army of social service workers and volunteers, working in pairs, fanned out across Lebanon to better understand the challenges of people experiencing homelessness and the scope of the crisis. On Thursday morning, survey teams retraced many of their steps to increase the odds of getting an accurate count of the city’s unsheltered population.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD, requires cities and towns that receive federal homeless assistance grants to conduct a count of the unsheltered in their communities every January. The surveys, known as point-in-time counts, were conducted this week throughout New Hampshire and Vermont.

“Point-in-time counts are important because they establish the dimensions of the problem of homelessness and help policymakers and program administrators track progress toward the goal of ending homelessness,” according to the nonprofit National Alliance to End Homelessness.

In rural parts of the country, tracking homelessness can prove difficult. Unlike major cities, the rural homeless aren’t usually found sleeping on park benches or wrapped in blankets on church steps. They’re often invisible.

In Lebanon, the city’s human services office and Listen, the longtime nonprofit that serves people in need, did much of the legwork for this week’s survey. They enlisted more than a dozen volunteers who served as troops on the ground.

The teams visited nearly 100 spots in Lebanon and West Lebanon where unsheltered people are known to have set up makeshift homes in the past or slept in their vehicles. Valley News photographer Alex Driehaus and I tagged along with two of the teams.

It behooves communities to get a true picture of their homeless population. Federal and state dollars are tied to the counts.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Three vie for two Hanover Selectboard seats

Three vie for two Hanover Selectboard seats

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

“When the count is higher, that means more resources come to Grafton County,” said Lynne Goodwin, the city’s director of human services.

Last year, largely through the survey work done in Lebanon, the county received $160,000 in funding spread over two years.

“Lebanon does an excellent job participating in the count,” said Jeanne Robillard, executive director of the Tri-County Action Program, a federally funded nonprofit based in Berlin, N.H., tasked to assist low-income residents in the northern part of the state, including Grafton County. “There were more communities in Grafton County participating in the (survey) this year than in years past, and we are very pleased with those community efforts.”

Information from this week’s survey, including the number of people found dealing with housing insecurity, will take a while to put together. But some of the numbers are already known.

This week, Lebanon has been paying for nine people, including a couple with an infant, to stay in motels at a cost of $100 to $150 a night per room. (Under New Hampshire law, municipalities must provide temporary housing for residents at risk of homelessness.)

The January 2023 survey counted 85 people in Lebanon who lacked a permanent place to stay. Of those, 62 were living in motel rooms. More often than not, their lodging was covered through the federal Emergency Rental Assistance Program, or ERAP, that Congress approved during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But now that ERAP money has dried up, it’s difficult to determine “what people are doing,” said Angela Zhang, Listen’s community services program director. “We’re really not sure.”

Are more people living in their vehicles? Are they spending the winter in tents in secluded areas? Have they moved away from Lebanon? Or did their fortunes change and they were able to find a place to live in the city?

Lebanon’s human services staff and Listen’s social workers are familiar with the hard-luck stories of the people they serve. The survey reaches beyond the anecdotal.

At 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Zhang and Jeanette Hutchins, a retired school nurse and first-time survey volunteer, headed for Densmore Brickyard.

It was Zhang’s second trip to the brickyard, a stone’s throw from the northbound lanes of Interstate 89 and not far from Lebanon High School. She had been there last August, when Listen and the city conducted an unofficial survey that found 32 people in Lebanon and West Lebanon without a permanent place to live.

The Densmore Brick Co. has been shuttered for 50 years. A collection of buildings with broken windows, partially collapsed roofs and walls spray-painted with graffiti is about all that remains.

With darkness settling in, Zhang shined her flashlight into what was once a beehive-shaped kiln made of bricks. Her light’s beam captured a small camping tent, set up on a wooden platform.

“We didn’t see this in the summer,” Zhang said.

There were also the remnants of a fire pit, built with bricks crafted by the company that provided the building blocks for Dartmouth College’s Baker Library, Lebanon City Hall, the Woodstock Inn and other Upper Valley landmarks. (In 2013, Hanover resident Stefan Van Norden made a documentary film, “Hand of Brick,” about the brickyard.)

Their curiosity piqued, Zhang and Hutchins looked around for footprints leading to the kiln and other buildings. An advantage of conducting the survey in the winter is it’s easier to detect whether anyone has been in the area recently. But the only tracks found Wednesday belonged to deer.

Their inspection of the brickyard complete, Hutchins and Zhang drove to the I-89 South rest area, just before Exit 18. These days, the state-managed property is used mostly as a staging area for road construction projects. Three portable toilets and vending machines with hot coffee, soft drinks and junk food are about the only amenities. Two phone booths, sans actual pay phones, represent a bygone era.

Zhang spotted a dumpster at the far end of the rest area. She lifted the bulky lid to peer inside.

“Unfortunately,” Zhang said, checking dumpsters has become a point of emphasis for her.

Last winter, the body of Jessica Morehouse, a 34-year-old mother of three girls, was found in a large pile of cardboard at the Casella Waste Systems recycling processing center in Hartford.

A police investigation found that Morehouse, who struggled with substance use and homelessness, had spent some nights in a dumpster filled with cardboard behind Listen’s thrift store and dining hall in White River Junction.

Morehouse’s death certificate indicated that she was inside the dumpster when it was “emptied into and compacted by (a) recycling truck” early one morning.

Satisfied that no one was inside the dumpster, Zhang and Hutchins headed for downtown Lebanon.

During her years as the nurse at White River School, one of Hartford’s three elementary schools, Hutchins had cared for kids whose families lived at the nearby Upper Valley Haven’s homeless shelter.

After attending a meeting of Housing First, a regional committee group overseen by Goodwin, Lebanon’s human services director, she decided to volunteer for Wednesday’s count.

“In retirement, I figured could still do things that were useful,” said Hutchins, who carried a backpack with packages of hand warmers to give to unsheltered residents found that evening.

Nationally, the first point-in-time count was conducted in 2005. The annual count has increased “public awareness of the homeless crisis and connected homeless individuals to services,” the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty said.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, homelessness had become a “national crisis, as stagnated wages, rising housing costs and a grossly insufficient safety net have left millions of people homeless or at risk of homelessness,” the law center said.

Still there’s a “significant undercount,” the law center’s research has shown. The annual survey doesn’t include people who are “doubled up” with family or friends due to economic hardships. It also doesn’t take into account so-called couch surfers.

Point-in-time counts “fail to account for the transitory nature of homelessness and thus present a misleading picture of the crisis,” the law center said.

Nationally, the January 2023 point-in-time count found that more than 650,000 people were “experiencing homelessness” on the night of the survey, a 12% increase from 2022, HUD reported.

When Goodwin started her job with the city in 2013, “homelessness wasn’t on my radar,” she said. The city didn’t even participate in the point-in-time count.

It all changed in 2016 with the discovery of a homeless encampment across from the Hannaford supermarket on Route 12A in West Lebanon. People were living in tents, vans and recreational vehicles on city-owned property. Residents and public officials were divided. Some people wanted to take a hard-line stance against folks they considered unwelcome squatters.

It led to the Lebanon City Council approving an ordinance that banned overnight camping on city land. Opponents argued the city was criminalizing homelessness.

In the end, a middle ground was reached. The group Housing First took the lead in seeking solutions to curb homelessness. Lebanon began conducting an annual point-in-time survey.

This week, the city, in partnership with the Haven, took another step forward with the opening of a 15-bed emergency winter shelter on Mechanic Street. People at risk of homeless now have access to a roof over their heads and hot meals at the shelter, which is open from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m. through mid-April.

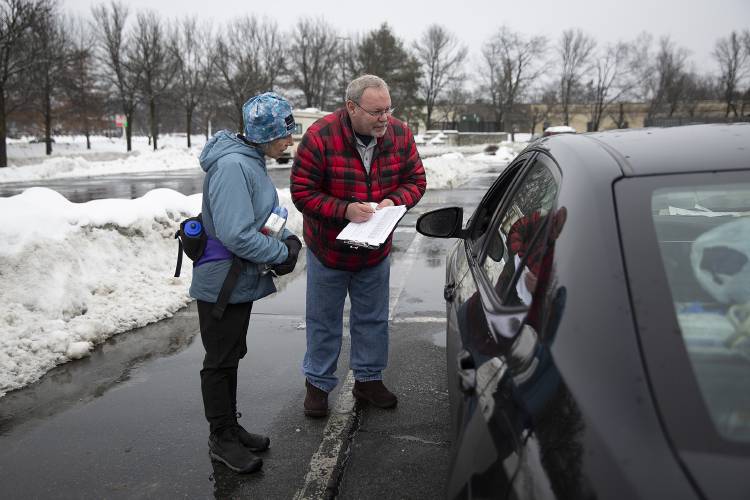

At 9 a.m on Thursday, Roscoe Putnam, who has worked at Listen for five years, and Stacey Chiocchio, community citizenship manager at Hypertherm in Hanover, started making the rounds on Route 12A.

They started at the lot behind Starbucks, which has been home to several people living in a recreational vehicle and a travel trailer for almost a year. In March, I wrote about Dave, who only shared his first name. He works at the Route 12A Burger King, which owns the lot and had given him permission to set up camp.

A few weeks ago, however, Dave and the occupants of the RV in the lot, who also work at Burger King, were informed by the Lebanon Planning and Development Department that they needed to move.

The Jan. 3 letter indicated they were violating the city’s zoning ordinance, which prohibits recreational vehicles from being set up in Lebanon’s “general commercial district.”

The owners were given 10 days to move. On Thursday morning, both camping vehicles were gone from the lot.

I’m not sure why the city picked now — at the height of winter — to force them out. I couldn’t reach Tim Corwin, the city’s deputy director of planning and development, who signed the zoning violation letter.

At Burger King, a manager told Putnam and Chiocchio that the occupants still worked at the fast-food restaurant but had moved their camping vehicles offsite.

Putnam and Chiocchio came across a RV in the parking lot leading to Walmart, but no one appeared home.

In the same large parking lot, Putnam pointed to a Toyota Corolla with its front bumper missing. Small cardboard boxes were stacked in the rear window.

The lone occupant sat in the driver’s seat, a paper bag from a fast-food restaurant in his lap. He sipped a soft drink.

“I’m Roscoe, from Listen,” Putnam said.

Putnam explained that the social service agency was conducting a survey to get “more funding for people who are having a tough time.”

The survey was “totally anonymous,” Putnam assured him.

The 34-year-old restaurant cook who had spent the night in his car, parked elsewhere in Lebanon, agreed to answer a few questions about his living situation and health.

Chiocchio, a first-time volunteer, handed him a plastic bag filled with items ranging from warm socks to Narcan, the nasal spray used to reverse opioid overdoses.

The man told Putnam that he suffers from major health issues, but “alcohol or drugs” aren’t a problem.

“Cigarettes are my vice,” he said, breaking into a laugh between puffs on a Marlboro. Putnam gave him a card with information on where he could go for a free meal and groceries.

“I don’t like asking for help,” the man said.

The response brought to light that “hidden barriers” remain for the Upper Valley’s social service organizations to overcome, said Chiocchio, who is finishing up a six-year stint on the Upper Valley Haven’s governing board. “There are still stigmas attached to being homeless that I hadn’t thought about,” she said.

Walking through the slushy parking lot, Chiocchio and Putnam came upon an older man sitting in his van that had a Maine license plate.

The snow around the van indicated the van had been in the same parking space overnight, arriving before the lot was plowed.

“I just moved to the area,” he said, mentioning that a job had fallen through, but he expected to find work soon. “I choose to live this way.”

Putnam told him about Listen’s food pantry and community dinners. The survey was a way to get more funding for people in need, Putnam added.

“I appreciate what you’re doing,” the man said. “Thank you so much.”

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Students take down pro-Palestinian encampment at UVM

Students take down pro-Palestinian encampment at UVM Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school

Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school