Jim Kenyon: Prosecutor rightly abandons case

| Published: 03-04-2023 8:40 PM |

Less than 24 hours before Friday morning’s court hearing to restart criminal proceedings against Scott Traudt for allegedly assaulting a Lebanon police officer in 2007, Grafton County Attorney Marcie Hornick ended the charade.

It was the right decision. But what choice did she have, really?

Even if Hornick had eventually secured a guilty verdict, Traudt would have still walked out of the Grafton County courthouse in North Haverhill a free man.

Traudt, 57, already served his time — a minimum one-year prison sentence — more than a decade ago. A jury had found him guilty of assaulting then-Sgt. Phil Roberts, now Lebanon’s police chief, during a late-night traffic stop on Route 12A.

In January, Superior Court Judge Peter Bornstein, who presided over Traudt’s 2008 trial and sentenced him to prison, set aside the felony conviction.

With new information becoming public in the last year or so, it’s “undisputed” that either the Grafton County Attorney’s Office or the Lebanon Police Department “knowingly withheld evidence” that would have bolstered Traudt’s defense at trial, Bornstein wrote in declaring the case be “revisited.”

The judge’s ruling left it up to Hornick to decide whether to bring the case again.

Elected for the first time 2018, Hornick wasn’t involved in Traudt’s original prosecution that drew Bornstein’s ire in his sharply worded 18-page ruling.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

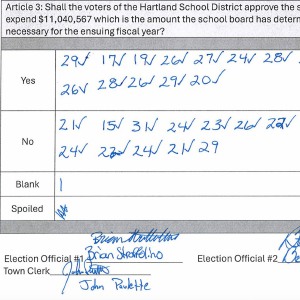

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

By seeking a retrial, Hornick could have scored brownie points with many in the New Hampshire law enforcement community who have no love lost for Traudt. Since his release from prison, Traudt has embarked on a one-person crusade to discredit Lebanon police and scrutinize the conduct of cops, in general.

Too often, prosecutors see their role as working hand-in-hand with police. To Hornick’s credit, she maintained her independence.

After a “careful review of the file,” re-trying the case “just didn’t make sense,” Hornick told me Friday afternoon.

In January, Bornstein ruled the “state did not meet its burden to show beyond a reasonable doubt that the failure to disclose certain evidence did not affect the outcome of Mr. Traudt’s trial,” Hornick said.

“He’s had his punishment,” she added.

Before reaching her decision, Hornick had several conversations with Roberts. She considers him the victim in the case.

Although Traudt was found guilty of assaulting Roberts, the jury cleared him of a simple assault charge against then-Lebanon police Cpl. Richard Smolenski.

On Friday, Roberts told me that he understood Hornick’s decision and the reasons behind it. “I completely left it up to her,” he said.

Hornick and Roberts are both realists.

As Bornstein pointed out in his ruling, prosecutors have no video evidence of the traffic stop or the ensuing scuffle that led to Traudt’s arrest. Prosecutors based their case largely on the testimony of Roberts and Smolenski.

In a retrial, Smolenski would have become the elephant in the courtroom — if Hornick could have called upon him at all.

Under the law, the government must inform anyone accused of a crime about exculpatory evidence that could be used to impeach a police officer’s testimony.

That didn’t happen in Traudt’s 2008 trial.

After years of literally fighting city hall, Traudt forced Lebanon officials to turn over Smolenski’s disciplinary records. The city only did so after the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that internal investigations into alleged police misconduct were no longer automatically exempt from the state’s right-to-know law.

Lebanon police records showed Smolenski had been suspended for three days following an internal investigation in 2006, stemming from his affair with an 18-year-old woman. Smolenski had “used his position” as a police officer to help the woman by “contacting an individual with whom she had had a conflict and ordered the individual to stop harassing her,” Bornstein wrote.

“Given that Smolenski’s testimony supported the facts for the assault against Chief Roberts, for which the jury found (Traudt) guilty, the State’s failure to provide the undisclosed evidence to the defendant may well have improperly affected the outcome of the trial,” the judge concluded.

Smolenski, a Lebanon police officer for 18 years, was fired in 2021 after being charged with stalking a woman he’d previously had a romantic relationship with. He’s pleaded not guilty to a misdemeanor.

I’ve heard lawyers say every case has good facts and bad facts. Smolenski’s credibility would have been on trial. I suspect that figured into Hornick’s decision.

It’s also about fairness. Traudt has been through enough.

With a felony conviction — the only mark on his criminal record — Traudt could no longer work as a military contractor, a job that had taken him to the Middle East and Afghanistan.

This winter, he’s driving a delivery truck for a propane company. In the spring, he’ll go back to his job as a commercial fisherman.

“I’ve paid a huge price in all of this,” he told me when we talked on Friday.

Since his release from prison in 2010, Traudt has spent countless days making public records requests and filing court paperwork, often representing himself, to clear his name.

On Thursday afternoon, his lawyer, Jared Bedrick, of Concord, gave him the news that hours earlier Hornick had filed a “notice of nolle prosequi.” The Latin phrase (I looked it up) means “not to wish to prosecute.”

And with that one-page court document, Traudt’s wish had finally come true.

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Kenyon: No respite from conflict in Upper Valley

Kenyon: No respite from conflict in Upper Valley A Life: Peggy Thorp ‘was critical to getting it all done’

A Life: Peggy Thorp ‘was critical to getting it all done’