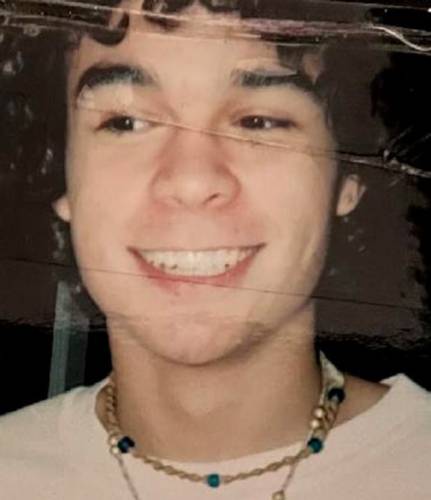

Kenyon: Family and friends mourn Upper Valley man who struggled along ‘a difficult path’

| Published: 07-08-2023 7:54 PM |

When Hartford Dismas House needed someone to tell its story, the nonprofit that provides affordable lodging and meals for people coming out of Vermont’s prisons often turned to Tommy Shea.

Several years ago, Shea was dispatched to Montpelier to educate state lawmakers on the importance of transitional housing for former inmates. At other times, he was called upon to talk with donors and volunteers at Dismas events. In 2017, Shea sat down with me for an interview about his struggles with painkillers and heroin that had tormented him since he was a teenager.

If sharing his life experiences could benefit Dismas House in some way, Shea was willing to help.

One of the occasions was a Dismas fundraiser for 60 people at John and Nan Carroll’s home in Norwich.

“I remember at the time thinking it took a lot of courage for him to stand up in front of people he didn’t know and talk about his life,” John Carroll, a former state senator, said in a phone interview last week. “He was a really capable kid.”

Six months ago, long after he had moved out of Dismas in Hartford Village, Shea agreed to participate in a Dismas podcast. But when it came time for the recording, he didn’t show up.

Friends and family feared that Shea, who lived alone in a downtown White River Junction apartment, was slipping away.

“He’d get clean for a couple of weeks and then he’d relapse,” said Nicolle Canales, a cousin who lives in Randolph. “It was always off and on.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

About two weeks ago, a concerned neighbor — after not seeing Shea for a while — called Hartford cops, who responded to his apartment on South Main Street for a so-called welfare check. They found Shea’s body in the apartment’s kitchen, Canales told me.

He was 34.

Hartford police aren’t saying much, citing an ongoing investigation. But there’s nothing I’m aware of that suggests foul play.

Police are waiting for results of toxicology lab tests before releasing any information, Hartford Chief Greg Sheldon said. A spokesman for the Vermont Department of Health, who sent me a copy of Shea’s death certificate, said it could take a few weeks before the test results are known.

If Shea succumbed to an opioid overdose, which is what circumstances suggest, it’s an all too common tragedy.

In the first three months of 2023, Vermont registered 55 opioid deaths — 10 more than the three-year average through March. Six of the fatal overdoses occurred in Windsor County and three were in Orange County.

Shea was a “loving soul who faced tremendous obstacles throughout his life,” Canales posted online. “Addiction took its toll, leading him down a difficult path from which he couldn’t escape.”

In talking with Shea in 2017, I learned that he was born in Lowell, Mass., to a mother who was a heroin addict and a father he never met.

At age 7, Shea moved with his three sisters to Windsor, where his grandmother lived. His mother was around — sometimes — but eventually, “she couldn’t handle it,” Shea said.

Starting when he was 13, Shea was placed in four foster homes in five years. His fondest memories were in Hanover, where he played football in middle school and for the first year of high school.

“I thought of Hanover as being a ritzy town, where I was going to get picked on because I didn’t have nice clothes,” he told me in 2017. “But kids were really nice. They were down to earth and asked me to hang out.”

In high school, however, Shea showed that he wasn’t much for following rules, such as curfews, which became problematic for the Hanover family that took him in. Shea was transferred to another foster home in Hartford.

Sage Barry, a football teammate, was Shea’s best friend while he lived in Hanover. They stayed in touch after Shea moved to Hartford.

The move was tough on Shea, Barry said. “He didn’t get along well” with his new foster mother, Barry said last week. “He didn’t feel like he was part of her family.”

At 17, Shea was arrested for shoplifting in Hartford. As a first-time offender, he entered a court diversion program, which would have allowed him to avoid a criminal record. But he failed to complete the program.

He dropped out of Hartford High School, and after leaving the foster home began living out of a tent and couch surfing.

He started using Oxycontin, which he said eased his bouts with anxiety.

“It helped me feel more normal around other people,” he said in the 2017 interview. “I could deal with things easier.”

When his prescription painkiller habit became too costly, he turned to heroin.

Within a few years, his rap sheet grew to a half dozen pages for theft and other nonviolent offenses.

But it wasn’t always doom and gloom.

For a while, Shea beat back his demons. He entered drug rehab, earned his high school diploma and enrolled at Vermont Technical College in Randolph.

Then his life unraveled — again. Two days after his 22nd birthday, Shea’s mother died from a drug overdose. Halfway to an associate’s degree at VTC, he suffered a relapse. Later, his younger sister was killed in a motorcycle crash.

In 2016, after getting nabbed in a Vermont State Police raid in Bethel, he pleaded guilty to possession of heroin. He spent seven months in prison.

With all he’d been through, Shea had “every excuse you could have, but he never blamed his problems on his past,” said Jeff Backus, who was Dismas House’s assistant director when Shea arrived in 2017.

Backus remembers Shea as someone who “craved knowledge and loved to read. He could talk about anything, politics or whatever.”

While at Dismas, Shea found a job behind the deli counter at Dan & Whit’s General Store in Norwich, where he’d worked in high school. After finishing a shift, Laura Fraser, a manager at her family’s store, sometimes gave him lifts to Hartford. On the short drives, Shea spoke with candor about trying to wean himself off methadone, a highly regulated medication used to treat heroin and painkiller dependence.

“He was trying so hard to get his life on track,” Fraser said.

Shea was interested in learning a trade. Meanwhile, he bounced from one menial job to another. He worked as a dishwasher and a custodian.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Barry, his best friend from his Hanover days, rented him a room at his house in White River Junction. The insecurities that afflicted Shea as a teenager still plagued him a decade later, Barry discovered.

“Any girl who showed an interest in him, Tommy fell hard for,” Barry said. “He just wanted to be loved.”

After a bad breakup a few years ago, Shea “might have relapsed without me knowing about it,” Barry said.

Shea moved out shortly thereafter. Canales, his cousin, saw him for last time in late May. After he’d experienced car trouble on Interstate 89 in Bethel, she picked him up at a gas station.

“He was a little despondent over his car breaking down,” Canales recalled. “There was a (trade apprentice) program that he wanted to start, but didn’t know if he could without a car.”

Backus, who left Dismas this spring for a job with the Upper Valley Haven, had already heard about Shea’s death when I called him last week.

“Of all the losses that I’ve had over the years, this is probably the hardest,” Backus said. “I wished I’d stayed in touch with him better.”

On Friday, Canales and Shea’s sisters were finalizing plans for an outdoor event at a Randolph park that would serve as a remembrance. I suspect it will be fairly well attended.

As Backus puts it, “Tommy was so easy to root for.”

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Developer seeks to convert former Brookside nursing home to apartments

Developer seeks to convert former Brookside nursing home to apartments