In Vermont, water issues require site-specific solutions

| Published: 07-31-2023 5:05 AM |

ROYALTON — Until midday Thursday, more than two weeks after this month’s historic flooding, customers of the town’s volunteer-run fire district, which brings water to 200 users in South Royalton village, had to boil their water for 60 seconds before using it.

“We made it through, but it was a pain in the neck,” Royalton Selectboard member Tim Murphy said Friday after the boil notice had been lifted.

Murphy lives in the village and endured the weeks of drudgery himself, but he was mostly concerned about the town’s restaurants, which couldn’t adapt as easily when water used for preparing food and washing dishes is compromised.

“It was rough,” said Lauren Adamoli, owner of First Branch Coffee on Chelsea Street. She hauled 10 gallons of water from her home in Tunbridge each day and had to strike espresso drinks from the menu entirely.

“For a coffee shop, espresso is the heart of your business,” Adamoli said. “I’m just now getting to the point where I’m going through the numbers, but we definitely saw a big financial hit.”

The village was put on a boil notice after floodwaters and heavy rain stirred up debris in the White River, the town’s primary drinking water source, and in its backup reservoir, Lake John.

South Royalton is among the nearly 20 Vermont communities that were forced to issue boil notices this month. As waters have receded in the last few weeks, they left behind renewed attention on Vermont’s aging patchwork of drinking water infrastructure. Many systems are in need of upgrades, but despite the availability of federal funding, they seem unlikely to receive them.

“In 30 years, I don’t think we’ve been on a boil notice that has lasted this long,” said Judy Hayward, volunteer administrative assistant for Royalton Fire District No. 1. Royalton is one of 35 communities in the state that utilizes surface water sources — which could mean lakes, streams, rivers or reservoirs — for its drinking water.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

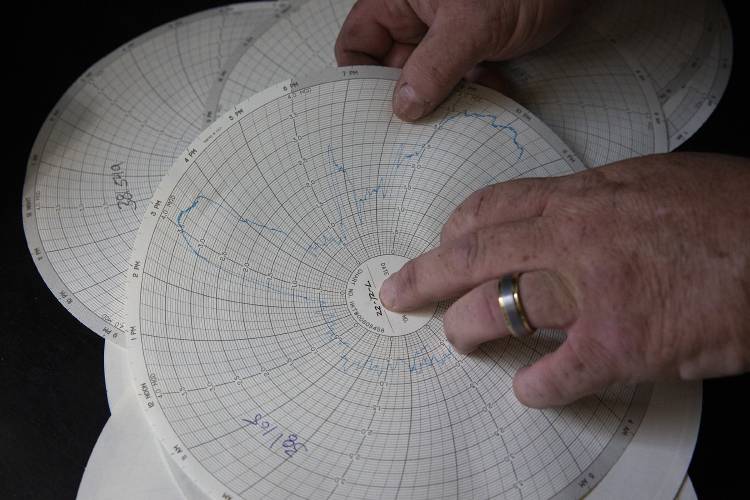

With pervasive rain in the weeks after the flooding, the water in Lake John kept getting “riled up,” and the town’s water operator, Wayne Manning, was left to aim at a moving target, scrambling to concoct the right chemical combination to treat it.

“He deserves a medal after this,” Hayward said about Manning’s efforts.

Manning’s brother, Theron, is the chairman of the prudential committee, the governing board for the fire department, which is also volunteer run.

“Both Wayne or Theron were in contact with the state every day by phone, or someone from the state came to the site,” she said.

Royalton’s issues were a site-specific problem that had a site-specific resolution, Hayward said. It was a different set of circumstances than in Woodstock, where water was totally offline for 11 days, she said.

“It’s funny, when you look at a pervasive storm like this, which impacted all of Vermont to varying degrees, there are still really specific solutions,” she said.

Across the state, “changes in topography, changes in service areas for these (water) systems, mean that (they) need to be managed and handled one by one,” said Ben Montross, drinking water program manager for the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.

Unlike Royalton’s troubles with its exposed surface water, Marshfield, Vt., which was also on a boil notice until late this week, takes its water from wells — or groundwater aquifers, in industry-speak — and lost pressure in the system of pipes that distributes its water to users after a landslide washed out the area where the village water system is located.

Woodstock Aqueduct Co., the private company that provides water to Woodstock Village and part of West Woodstock, was sent completely offline after flood waters ripped through a section of its distribution system, damage compounded by logistical issues when it came to delivering the replacement piping. Woodstock was one of two towns across the state that had to issue a more stringent do-not-drink notice, Montross said.

Woodstock Aqueduct Co., is one of about two dozen privately owned water systems of the state’s more than 400 community water systems.

The Woodstock Planning Commission said the company has not maintained its water system properly and has had outstanding issues with the state since last summer, according to reporting from The Boston Globe last week. Some Woodstock residents are advocating for change in the utility’s governance, hoping to bring control of the water into the town’s hands.

But while private companies make up only a sliver of water systems in Vermont, the rest is in no way homogeneous. It’s a “diverse landscape,” Montross said.

There are just shy of 1,400 public drinking water systems in the state. The bulk are community systems, like those in Royalton and Woodstock, “and that’s what we’ve been dealing with the most (after the flooding),” he said.

The rest are “non-community systems,” which can include rest stops, state parks, campgrounds and schools. The Sharon Academy, for example, has its own source of water.

Community systems can be run a number of different ways. Some are private, managed by a volunteer board — like the Royalton Fire District — or public, and run by a full-fledged, town-operated public works department.

Drinking water systems in Bethel and Windsor, which are run by the towns, fared well enough.

Windsor has two wells, each about 100 feet deep and across from Price Chopper, that haven’t given the town any trouble in the 35 years that Mike Reynolds has served as the town’s water operator.

The town’s water has about 1,000 users, and Reynolds said there are no pending plans for upgrades. “When it comes to water, we have plenty,” he said.

Windsor’s wastewater treatment facility, which was built during the town’s industrial heyday, also has wiggle room.

“We were designed to see 1.2 million gallons of sewer flow a day, but we see around 200,000,” Reynolds said. “We have room to expand.”

In Bethel, drinking water comes from two gravel-packed wells, where pumps draw water up into two storage tanks on either end of town before it drains back through gravel to feed the system.

“We had one well near the White River that we were concerned was potentially going to get flooded, but the water luckily didn’t get high enough,” said Richard Manning, Bethel’s chief water operator.

In 2011, Tropical Storm Irene took Bethel’s drinking water system offline for a number of days.

As far as infrastructure upgrades to the water system since, “everything is pretty much still the same as when Irene happened, but luckily this time we didn’t have the same volume of water,” Manning said.

But Liz Royer, executive director of the Vermont Rural Water Association — a nonprofit that does on-site assistance for community water systems and offers training curriculum for water operators — urges against taking a water system’s success after this month’s flooding at face value.

Bethel made it through this flood fine, but a close call doesn’t justify proceeding with business as usual.

“The focus has been so far on emergency repairs and getting pipes put back together,” Royer said. “That’s typically what (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) likes to fund — putting things together how they were before.”

But that leaves infrastructure vulnerable to the same problems that damaged it, and the risk will increase as climate change brings more rain, and more drought, to New England.

Still, getting towns to take upgrades seriously is difficult, Royer said.

“After those initial emergency repairs have been made, how do you then go back and convince someone funding you that it’s more important to dig up that pipe and put it back some where else, or build it with a different material,” she said. “It’s a little bit of a challenge and we’re all trying to figure it out as we go.”

Flooding and other extreme weather events call into question the efficacy of infrastructure that is often taken for granted, Royer said.

“Aging infrastructure is an issue at all times, and flooding is one of those times when it becomes more visible, literally,” she said. “The road washes away, the river crossing is visible, it’s kind of an opportunity to just educate folks. A lot of systems have very old pipes, drinking water and wastewater, and we need to be proactive about replacing those.”

After flooding, FEMA and state money are easier to come by. Royer recommends that it be put to best use.

“We’re at that point where it just really isn’t going to make any financial sense to ignore things until they break,” she said.

“We need to be asking ourselves: What can our infrastructure withstand and what can we do to make it better now that we have the attention of the federal government?”

Frances Mize is a Report for America corps member. She can be reached at fmize@vnews.com or 603-727-3242.

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community