Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

|

Published: 04-12-2024 9:02 PM

Modified: 04-14-2024 6:38 PM |

Over the last decade, more than 150 men have found their way to the two-story, early 1900s clapboard house with a wrap-around front porch in Hartford Village. Some stay only a few months. Others for a year or longer.

But their reasons for wanting to make 1673 Maple St. their home are almost always the same. Fresh out of Vermont’s prisons, they arrive needing a roof over the heads, food in their bellies and a second chance.

Hartford Dismas House, which opened 10 years ago last month, offers all three.

It’s one of five properties operated by Dismas of Vermont, a nonprofit that for nearly 40 years has provided transitional housing to people whom society too often writes off as lost causes.

It’s important not to forget that “these are our neighbors,” said retired Upper Valley Haven Executive Director Sara Kobylenski. “They’re people who are coming back home to live in our communities.”

With the Upper Valley’s lack of affordable housing, it only stands to reason that guys coming out prison have a better chance of making it if they can start out in a supportive environment.

Hartford Dismas residents pay $85 a week in room and board. The eight men currently living in the house range in age from their early 20s to mid 50s.

“It’s nice having a range,” said Tom Grillo, who started as house director in 2022, after years of doing social work at a residential substance use treatment center in Littleton, N.H. “The older guys are more mature and can be role models. They see the dangers and temptations that are out there.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

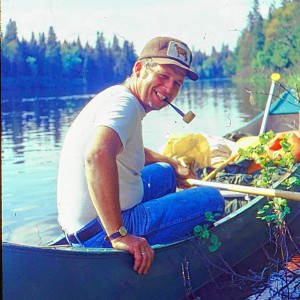

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

Dismas interviews potential residents while they’re still incarcerated, in part, to make sure they understand house rules and are also a “good fit” for the house, Grillo said. (For a while, Hartford Dismas’ residents included women. Then in 2021, Dismas of Vermont founded a house solely for women in Rutland.)

Hartford Dismas is a sober living house, which to an extent relies on an honor system. Run on a shoestring budget with only three staff members, 24-7 supervision isn’t possible, and not even preferable. Trusting residents to make good decisions is part of reintegrating in the outside world.

Residents “do the heavy lifting,” said Dismas of Vermont founder Rita McCaffrey, of Rutland. “We can’t do it for them. They have to want to do it for themselves.”

On weekdays, when the Dismas staff is tucked away in their small offices, the nine-bedroom house gives off a quiet, no-one-is-home vibe.

It’s meant to be that way.

After settling in at Dismas, residents need to find jobs that not only cover their room and board but allow them to save enough to eventually move into their own places.

At dinnertime, the house comes alive. Unless they’re working or have appointments tied to their parole, residents are expected break bread together each weekday evening.

“A lot of the men have never had the experience of sitting down for a family-style dinner,” Grillo said. “They’re used to just eating and running, but I think they come to enjoy the social part of sharing a meal.”

On Monday, a half-hour before dinner, resident Dana Osmer made pitchers of iced tea in the kitchen.

Osmer, 29, told me that he didn’t mind if I used his full name in this column. Unlike other times when his name appeared in a newspaper, this was something his mother could be proud of, he said.

“I’ve been nine-years clean,” he said.

Osmer, a Lebanon High School graduate, traces his battle with substance use to when he suffered a compound leg fracture and other injuries in a dirt bike accident. By the time a doctor stopped writing him prescriptions for Percocet, a powerful pain reliever, it was too late, Osmer said.

He turned to heroin. “It took the pain away,” he said. To support his habit, Osmer said, he started “selling mass quantities of meth.”

He spent 2½ years behind bars in Vermont and New Hampshire on drug and other charges before arriving at Dismas last spring.

Osmer now works as a line cook at a Hartford restaurant, riding one of Dismas’ two donated e-bikes to his job on the other side of town that pays $18 an hour.

“Dismas was my only ticket out of prison,” Osmer said. “If you don’t have a job and a place to live, you’re going to fall right back into your bad habits.”

The 10-year history of Hartford Dismas House is partially told in dozens of color photographs that decorate the dining room walls and hallway.

They depict residents on weekend group excursions — fishing on Lake Champlain, snowmobiling in the mountains and horseback riding on grassy trails.

While the photos are filled with smiling faces, a few serve as solemn reminders. Not everyone who enters Dismas ends up successfully reintegrating into society.

About 15% of residents are arrested for new offenses. It’s a much better batting average than when people go straight from prison to living without transitional housing.

Still Dismas doesn’t pretend to be perfect.

A Dismas resident pointed me to a photo of a man in his 20s who was learning the art of fly fishing during a weekend trip a few years ago. Another picture showed the same bearded figure standing outside the Ben & Jerry’s ice cream plant in Waterbury, Vt., with his Dismas buddies.

In the end, however, Paul Blanchard III couldn’t shake his demons.

Blanchard, by his own “self-admission was a heroin addict,” his mother, Sue-Ellen Hilliker-Parmenter, told me.

His family supported him through the difficult times. He completed two substance use residential treatment programs, only to suffer relapses.

Blanchard served four months in prison on a firearms conviction before moving into Dismas. Six months later, he was expelled from Dismas for failing multiple drug tests that were required as a condition of his release from prison, Hilliker-Parmenter

He was homeless for a while “before he knocked on my door,” his mother said. “He didn’t want me to know he was using again.”

His family set him up in an apartment in White River Junction. “He was trying to get his life together and he’d been looking for a job,” Hilliker-Parmenter said in a phone interview.

But he was struggling more than he let on. On Nov. 25, 2022, Blanchard died in his apartment from an accidental drug poisoning.

What Blanchard thought was heroin turned out to include a mixture of Fentanyl and Xylazine, a livestock sedative, according to his Vermont death certificate.

He was 29.

The tragedy is a reminder that “you can’t know what is in street drugs, and they can be far more powerful than you think,” a spokesman for Vermont Department of Health told me.

Since opening its first house in 1986 in Burlington, Dismas of Vermont has relied on volunteers — often from local churches — to prepare the evening meal and initiate dinner table conversations.

“It builds our community,” Grillo said. “The guys get to realize that there are people out there who want them to succeed.”

At the same time, volunteers benefit from the face-to-face interactions.

The volunteers can see “these aren’t bad guys,” Grillo said. “They’re people who have made mistakes.”

The dinners bring together people who otherwise wouldn’t “get to know each other,” said Bartlett Leber, who chairs the Hartford Dismas board.

On Monday, Sue Carpenter, of St. James Episcopal Church in Woodstock, brought pans of lasagna.

“Dismas is a great organization and I like to help out where I can,” she said. “The guys who live here are super. They’re trying to get on a straight path.”

After residents and guests were settled into seats at the long, rectangular dining table, Wendy John dished out plates of pasta, garden salad and corn bread.

As Dismas’ transition coordinator, John helps residents with job searches and other tasks, such as setting up bank accounts.

But like Grillo and Gale Nadeau, the assistant house director, John does a lot that’s not part of her job description. When available, they drive residents who don’t have cars — which is most of them — to work and counseling sessions. They go with them to the nearby Listen Center’s thrift store to shop for work clothes and winter jackets.

People coming out of prison face “so many challenges,” Leber said. “Just figuring out how they’re going to get to work is a challenge.”

Leber’s board has challenges as well, starting with raising $100,000 or more in private money each year to support an annual $350,000 operating budget.

An agreement with the Vermont Department of Corrections brings in slightly more than $200,000 a year. Considering the annual cost of keeping someone locked up is often $50,000 or more, it’s a good deal for taxpayers.

The Dismas board also recognizes that its core volunteers aren’t getting any younger. Recruiting people who have the time and energy to cook dinner five nights a week is a board priority.

“We’re trying to get our name out there,” Leber said, citing a monthly speaker series that tackles criminal justice issues.

On Monday, Grillo jump-started the dinner conversation by asking each of the 14 people at the table to talk briefly about something that they were grateful for that day. It also happened to be the day of the solar eclipse.

When it came time for Parker Clark to speak, he smiled at the young woman sitting next to him.

“I’m grateful for Emily picking me up at work today so we could watch the eclipse together,” said Clark, who with help from his stepfather landed a job in construction after arriving at Dismas last summer.

Clark, who turns 22 this month, and Emily Waterman, 22, began going out in January, after meeting at Walmart in West Lebanon. He was looking at video games when Waterman caught his eye.

He invited her to a movie that night in Lebanon with a couple caveats — she needed to drive and also have him back at Dismas House before his 9 p.m. curfew.

In the short time he’s been out of prison, Clark has found that once strangers hear about his legal troubles they tend to shy away.

Clark grew up in Bradford, Vt., before his family moved to the Northeast Kingdom when he was in high school. At 20, he didn’t have a criminal record until a night of heavy drinking and poor decisions resulted in a friend suffering serious injuries. Clark spent 15 months in prison.

“I get a lot of, ‘Oh, you’re a felon?’ ” Clark said.

And that’s where the conversation usually stops.

But for Waterman it wasn’t a deal breaker.

“I’d heard of Dismas,” she told me. “I was OK with it.”

When they go to movies, he insists on paying.

“I can afford it,” he said.

Clark’s job with a small construction company, which this week had him on a crew replacing a barn’s tin roof, pays $22 an hour. In prison, he worked in the dining hall for $2 a day.

“I’m in a lot better place now,” he said.

(For more information about substance use treatment, overdose prevention resources and other services, visit VTHelpLink.org or call 802-565-LINK.

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Big drop in tuition and aid is boosting Colby-Sawyer

Big drop in tuition and aid is boosting Colby-Sawyer  How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war

How NH Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut used his office in the culture war