Dartmouth protesters mark 50th anniversary of Parkhurst Hall occupation

| Published: 05-10-2019 6:16 PM |

HANOVER — Dozens of students who occupied Dartmouth College’s main administration building in the spring of 1969 to protest the Vietnam War are returning to campus this weekend to mark the 50th anniversary of the event.

Many of the protesters were jailed, and the event remains a touchstone in their lives.

David Green, the only participant who was expelled from the college, said that the protest at Parkhust Hall was the “most vivid electrifying memory” that he has. He already had been on probation for a protest in which a crowd of students blocked an Army recruiter from entering a building.

“We were locked arms on the steps of Parkhurst, shouting ‘U.S. out of Vietnam. ROTC out of Dartmouth,’” he said. “It thundered out of the front doors.”

The protest specifically was directed toward the campus presence of the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, which came to be seen as a symbol of the college’s implicit endorsement of the Vietnam War, according to Jim Wright, who arrived on campus as a history professor shortly after the occupation and later served as Dartmouth president from 1998 to 2009.

Back in the 1960s, roughly 200 Dartmouth students graduated into military service from ROTC each year, and anti-war activists wanted to abolish the program in Hanover immediately. Others wanted to keep it or phase it out over time, allowing current students to retain their ROTC scholarships.

In the afternoon of May 6, 1969, a couple of dozen students and community members occupied Parkhurst Hall.

The occupation started when the students gathered at the building, which includes the Dartmouth president’s office, in the afternoon. A few hours later at 8 p.m., a sheriff read an injunction warning that anyone remaining in the building after a certain time would be arrested. At 3 a.m., state troopers arrived, broke down the doors with a battering ram and carried out the protesters. More than 50 of the protesters were convicted of contempt of court within days of their arrests and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

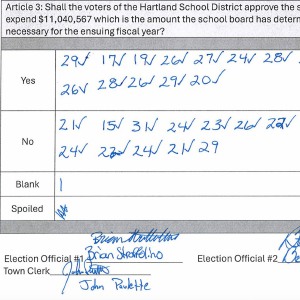

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

“We did not expect to be put in jail for a month immediately. In hindsight, we should have planned a legal strategy to obstruct and slow down the judge,” said Guy Brandenburg, a Dartmouth alumnus who was among the protesters.

Some faculty also participated, and William Kunstler, a prominent attorney for what were then seen as radical causes, represented two professors before a Dartmouth sanctions committee.

“There are some situations where you must break the established order,” Kunstler said at the time.

When David Aylward arrived on campus as a student in 1967, holding anti-war sentiments was “not normal.”

“You were regarded as a bit of a freak. Dartmouth was a very homogenous place,” said Aylward, who became the editor of the student newspaper, The Dartmouth, in 1970.

However, as the Vietnam War continued, the debate went from focusing on the pro and cons of war to whether ROTC ought to be kicked off campus immediately or in a year, Aylward said.

In the previous year, the peace line that gathered on the green became a fast in protest of ROTC. Aside from drinking a cup of orange juice and taking a multivitamin, the students didn’t eat and started discussion across campus, he said.

The sentiments on campus were a confluence of the anti-war and civil rights movements. According to Aylward, suspicion of the government increased, and there was an awareness of both the oppression of the Vietnamese and minorities in American cities.

“This wasn’t just a matter of public policy, it was a matter of my body getting sent to Vietnam to execute this war,” he said.

In particular, then-president John Sloan Dickey, a former Boston lawyer who had worked for the State Department during the Cold War, was less sympathetic to the anti-war cause. Wright had just arrived on campus and attended a faculty meeting that voted on whether to call an end of the Vietnam War.

“I recall his apparent and undisguised disgust with the faculty deciding they were going to vote on war and peace,” Wright said.

Up to 45 of the protesters are expected to gather in Hanover this weekend for discussions over how anti-war activism has impacted their lives and meet with current student activists including Divest Dartmouth, Aylward said.

While Aylward was abroad during the occupation, he was involved with the anti-war movement on campus and is attending the reunion.

Aylward said Wright convinced him to join a presidential campaign after college, which eventually led to a job on Capitol Hill and then law school. He also served as chief counsel and staff director for the House Telecommunications and Finance Subcommittee and more recently has worked to develop health systems, including programs for disadvantaged Americans.

Green said that he became involved with progressive politics again in 2015. He said he has worked with the Poor People’s Campaign and local organizations to support refugees and protest Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“There’s more to be done than showing up one day every four years to vote,” he said.

Prior, he worked as an acupuncturist and now works as the marketing director for a water filtration company.

As for Steve Tozer, another student protester, he said that his career has been influenced more by the consciousness he started to develop in college around inequity rather than the specific events of the anti-war movement.

“What did have an impact was coming to understand over time that spring and that school year that we have a culture in American society that is structured to protect privilege and vested interests,” he said.

That awareness translated into a career in education, and Tozer, who lives in a suburb outside of Chicago, now works to educate principals. He previously opened an alternative school and wrote a textbook on teacher education.

Brandenburg also worked in education but as a math teacher for middle and high school students in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t see any of us who have become bankers, industrialists or sell-out politicians,” he said.

Discussion panels will be held from 10 a.m. to noon and 1 to 4 p.m. on Saturday at the Howe Library. Participants are planning on gathering at noon on the steps of Parkhurst Hall for a photograph.

Amanda Zhou can be reached at azhou@vnews.com

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination