Can land conservation and housing development coexist in the Upper Valley?

| Published: 03-27-2023 12:46 PM |

WILDER — Henry Hazen’s family has owned Brookside Farm, which sits just where Dothan Brook crosses Christian Street, for seven generations. Previously a beef and vegetable operation, the farm is now used for boarding horses.

From the farm’s 174-acre perch, nearly two centuries of Hazens have witnessed the development that has slowly — and sometimes, quickly — hemmed in the property’s borders. Brookside is now sandwiched between the Olcott Drive and Billings Farm Road business parks, to the north and south of the property.

When housing construction ramped up in the 1980s, Hazen, 66, said he “really fought it tooth and nail.” He went to Hartford Planning Commission meetings to oppose Hemlock Ridge, a condominium complex across Route 5 from his property: “I went every Monday for three years trying to fight that.”

But these days, he’s “more mellow,” he said. “I’ve realized I can’t stop stuff, I can only get it to be as least impactful as possible.”

In the 1960s, the arrival of Interstate 91 cut Brookside in half, Hazen said. “I have 90 acres on the west side of the interstate, which is surrounded by heavy development. We have industrial parks on either side and condos across from us on Route 5,” he said.

Now, the Upper Valley is facing a new development challenge, one that appears to pit the desire for open space, like the Hazen farm, against the need for housing. It doesn’t have to be that way, both housing and conservation advocates say.

The 2021 “Keys to the Valley” report, created by a consortium of regional planning commissions, forecasts the need for 10,000 new homes of all sizes by 2030 to meet an Upper Valley population growing at a fast clip. This is around three times as many homes than were built in the region between 2010 and 2020.

The area also has a labor shortage. The two issues aren’t unrelated. As housing prices rise, a substantial portion of new housing stock should be affordable, the report says.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

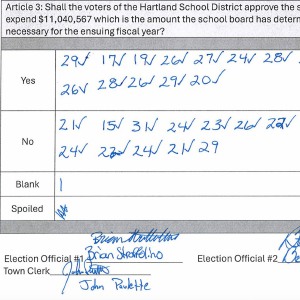

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

“We hear from our members all the time that they make an offer to somebody and then that person comes to try to find a place to live, to relocate, and either has sticker shock or is simply not able to find anything,” said Tracy Hutchins, president of the Upper Valley Business Alliance.

As the population of the Upper Valley continues to grow, the area faces pressure to protect open space from that growth, but also for it. Some municipal planners and conservationists are plotting out how the Upper Valley, in this moment of transition, can preserve its rural character for everyone, not just the people who own the land.

Around the time Hazen was making himself heard at planning commission meetings, his family sold a conservation easement to the Upper Valley Land Trust, or UVLT. The property can’t be used for anything other than agriculture.

Brookside could have gone the way of Hemlock Ridge — open space bulldozed in response to housing demand. But conserved, it plays another role.

The UVLT easement also produced the Hazen Trail, which follows a ridge for two miles above the Connecticut River through Hazen’s own forest and farmland. It connects Norwich and Wilder, taking advantage of the conserved land between industrial parks.

“There aren’t many other trails right in that area,” Hazen said. “I think the community appreciates it. I’ve had a lot of people comment on that, how nice it is to see a farm there and to have that trail.” (He does ask everyone to stay out of his hay fields, though).

A decade ago, UVLT ran a survey that polled people’s attitudes toward open space and conservation.

Renters, the survey found, felt more urgently about conservation than people who owned their house or their land. Similarly, people who lived on small lots felt more urgently about conservation than people who lived on larger lots.

Many land trusts think that their constituency is primarily owners of larger tracts of land, UVLT President Jeanie McIntyre said. “There’s a lot of communication developed towards those people. But if you think about it, this is really logical. If you own a large lot, you’re in control of it. You can enjoy it. Your enjoyment is not at risk of someone else’s decision making,” she said.

“If you live in an apartment building or in a subdivision of homes that are on one-third acre lots, your sense of risk to the open spaces that you depend on is very different.”

The people who need dense, cost-conscious housing are the same people who tend to support land conservation.

Mark Goodwin, a Lebanon city planner, is hoping to change the dialogue around land conservation and development.

Officials and residents of Lebanon have long nurtured “a lot of desire for open space,” but Goodwin said that until the 2021 release of the city’s Open Space Plan, the desire was only that.

He and his team behind the plan got busy mapping the general feeling that hangs heavy over much of the Upper Valley — a commitment to the rural character of the area that Hazen fought “tooth and nail” to protect — into a viable project.

The population of Lebanon grew more over the course of the last decade than any of the Upper Valley’s New Hampshire communities, according to 2021 census data.

The city also saw the construction of 942 housing units over the past decade, representing a 16.5% increase, which exceeds both the New Hampshire and Vermont rates, the city’s master plan says.

“The majority” of recent nonresidential development, which has also skyrocketed in Lebanon, has been “greenfield,” meaning it occurred on previously undeveloped land.

The Open Space Plan, adopted by the city’s Planning Board and Conservation Commission, calls for “redevelopment,” or “brownfield” development, instead.

“Some people think that open space and housing are a true one-to-one supply and demand ratio. They think that if we call for too much open space, that’s going to exacerbate the already exacerbated housing crisis,” Goodwin said.

“But that’s sort of a knee-jerk reaction. You have to move the audience beyond that. The housing supply model is far more complex than ‘is there land available?’ ”

The Centerra Business Park, Airport Business Park, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center campus, and commercial development along Route 12A are all located on former natural open space or agricultural land.

Still, more than 80% of land in Lebanon remains undeveloped. There are still two working farms in the city.

The Open Space Plan earmarks 686 acres of the city’s current open space for development.

On that land, developers could build the equivalent of three Centerra Business Parks, 10 apartment complexes like the Timberwoods, two subdivisions, and 170 single family homes, according to the plan.

The possibilities are promising, but for now, they’re still only possibilities.

There’s nothing to stop all this space from becoming single family homes, Goodwin said. “There’s very little regulatory control that would prevent that.”

Working with the White River Land Collaborative, an offshoot of Vital Communities, Sarah Danly is trying to brace the region’s agricultural land against the surge of outward spread.

Modernizing zoning standards to direct growth to central areas and hinder sprawl is a best practice for land conservation, Danly said. It could also help the Upper Valley grow more equitably.

The majority of the clean energy sector in New Hampshire notes hiring difficulties, a 2019 report said. To meet construction demands, the Vermont Department of Labor estimates that the state needs 5,000 new carpenters to meet demand over the next decade.

Lebanon, the commercial and residential heart of the Upper Valley, has shouldered much of the area’s growth, but smaller communities will also need to contribute to the housing stock, the Keys to the Valley report says.

Grafton, New London and Plainfield in New Hampshire, and Barnard, Fairlee, Sharon and Tunbridge in Vermont all saw gains in population in the 2020 census. Fairlee will need to develop upward of 100 new housing units by 2030, the report estimates.

In the last decade, Hanover built 450 housing units, Hartford added 323, and Claremont, 614. Norwich built 29 houses from 2010 to 2018.

Meanwhile, at $500,000, the average annual median sales price of single-family homes in Norwich was the highest of any town in Windsor County based on data from 2014-2018, according to the town plan.

“These high sales prices mean that few low, moderate or even middle-income households can afford to purchase a home in Norwich,” the plan reads.

Lebanon voters passed a flurry of zoning regulations earlier this month that allow for higher density development, which generally means the construction of lower-priced housing closer to municipal services, like public transportation.

Enfield and Bethel are among the smaller towns that have passed, or are considering passing, similar zoning bylaw updates, which grant exemptions on smaller-than-usual lots and affordable housing.

“A lot of single-family zoning, especially with large lot sizes, was put into place in a well-meaning attempt to conserve natural land by preventing overdevelopment, but it leads to sprawl instead of cluster development,” Danly said.

“That also makes each individual house parcel more expensive, and therefore less accessible.”

Economically disjointed growth, which doesn’t provide housing options for a range of income levels, will leave the region at a disadvantage, she added.

“If we try to prevent people from coming here, and there’s not more housing being built, it just means that the only people who move here are the people who can afford to buy 80 acres of forest,” Danly said.

Nonprofit affordable housing developer Twin Pines Housing Trust has found that protecting open space is just a matter of course.

Twin Pines focuses its housing efforts away from undeveloped edges and into village centers or downtown areas, where water and sewer infrastructure already exists, Executive Director Andrew Winter said.

Tracy Community Housing, next to West Lebanon’s Kilton Library, was an infill site. “We were able to remove a couple of rundown single family homes and replace it with 29 units of housing,” Winter said. “That’s what we’re trying to do, for the most part.”

A similar project that just recently broke ground, called River Walk — 42 units of housing located across from Listen in White River Junction — is also a “brownfield development.”

To have our forests and farms in mind means to have our eyes also on the nitty-gritty infrastructure projects in developed town centers that make infill development possible, McIntyre, of UVLT, said. “Your 30-unit development has its own water and wastewater system because there is no capacity to hook on to municipal ones outside of the very core of the Upper Valley,” she said.

“It’s concerning that outside of the sort of village cores, the ability to put in larger blocks of housing really depends on having a developer and a development plan that allows you to put in water and adequate wastewater treatment, sort of one development at a time.”

Without bolstered infrastructure — in all of the area’s town centers, not just the already dense ones — McIntyre foresees the Upper Valley ending up with pockets of “20, 30, 40 units of housing in this and that and another area,” she said. “It wouldn’t be coordinated to protect open space in a way that is connected and accessible to all.”

If money is funneled into infrastructure in town centers, McIntyre said, the available capacity will incentivize development there. This is especially important in smaller towns — ones that don’t have much of an established town center — and towns without zoning.

Bethel is scheduled to vote next month on a $2.5 million bond that would expand the town’s water capacity. With mostly state funding, Royalton is implementing $3.8 million in upgrades to its wastewater treatment plant in the hopes of nearly doubling the system’s capacity.

The pricey financing and construction of these infrastructure projects is a challenge, but could be well worth it, McIntyre said.

“The fragmentation of our landscape is a risk,” she said.

The story is different where protected land fragments development.

Norwich resident Selina French uses the trail on Hazen’s property, which McIntyre’s organization helped to conserve, to get to her grandchildren’s house in Wilder.

“I take it almost every day in the summer,” French said. “It’s a great little walk over.”

For residents like French, who spent two years searching for a rental house in Norwich, Hazen’s land is connective tissue between the two communities. The trail is part of what makes the house worth having.

Frances Mize is a Report for America corps member. She can be reached at fmize@vnews.com or 603-727-3242.

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination