Hartford voters approve school budget and building repair bond

HARTFORD — Voters approved the school district’s $51 million budget, as well as a $21 million bond for facilities repairs in Australian ballot voting Monday.The budget passed 728-622, or about 54% to 46%. The bond passed more narrowly, 712-634, or...

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Dartmouth President Sian Leah Beilock has made it clear the college views its men’s basketball players — and their recent historic vote to unionize — as a threat to ….Fill in the blank.The college’s bottom line? The status quo? The misconception that...

Most Read

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Enterprise: Upper Valley pet sitters discuss business growth, needs

Enterprise: Upper Valley pet sitters discuss business growth, needs

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

2024 Upper Valley high school baseball guide

2024 Upper Valley high school baseball guide

Canaan Elementary School has new principal

Canaan Elementary School has new principal

Editors Picks

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Sports

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

Once you’ve finally been to the top of the mountain, what do you do for an encore?That’s the challenge facing the Hartford High boys lacrosse program this spring. After multiple attempts that came up short, the Hurricanes ran the table en route to...

Ex-Virginia assistant Kirwan latest to step into the Big Green breach

Ex-Virginia assistant Kirwan latest to step into the Big Green breach

Durham combines strength, fitness on the trails

Durham combines strength, fitness on the trails

Out & About: Thin ice puts future of Upper Valley skating trails in jeopardy

Out & About: Thin ice puts future of Upper Valley skating trails in jeopardy

A Life: Chuck Hunnewell ‘was an intense competitor but a real gentleman’

A Life: Chuck Hunnewell ‘was an intense competitor but a real gentleman’

Opinion

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Hey, Major League Baseball, does the name Pete Rose ring a bell? Remember him, “Charlie Hustle”? One of the game’s greatest players, whom you banned for life in 1989 because he bet on baseball games?We ask because you have on your hands another...

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

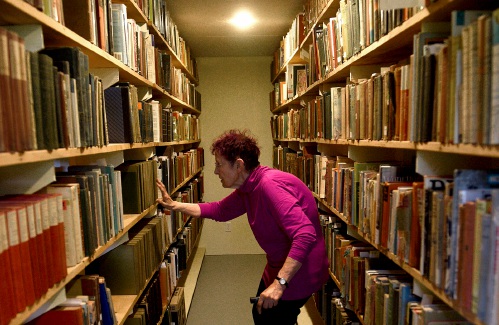

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

Photos

Acoustic music jam in White River Junction

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Arts & Life

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

It was Traffic vs. the Eclipse on Monday, a showdown of celestial proportions. Would I risk everything like Marco Polo who bravely set out to see the world, or follow the example of his brother Rocco, who said their hometown of Venice was “plenty good...

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Sunshine, snacks and laughs features of Bugbee’s solar eclipse party

Sunshine, snacks and laughs features of Bugbee’s solar eclipse party

Obituaries

Barbara Champagne

Barbara Champagne

reading, VT - A graveside service for Barbara "Bobbi" Champagne who passed away on January 26, 2024 will be held in St Mary Cemetery in Claremont, NH on Saturday, April 20th at 1PM. ... remainder of obit for Barbara Champagne

Josephine Tansey

Josephine Tansey

Josephine (Bertino) Tansey Rutland, VT - Josephine (Bertino) Tansey died Saturday morning (April 13, 2024) at the Mountain View Center Genesis Healthcare in Rutland, VT. Mrs. Tansey was born... remainder of obit for Josephine Tansey

Sharon Nordgren

Sharon Nordgren

Hanover, NH - Sharon L. Nordgren 10/21/1943-02/10/2024 Sharon L. Nordgren passed away on February 10th, 2024 in Hanover, New Hampshire. She was 80 years old. Sharon was born Octobe... remainder of obit for Sharon Nordgren

Winnifred Rae Dennis

Winnifred Rae Dennis

Winnifred Rae (Winnie) Dennis West Lebanon, NH - Winnifred Rae (Winnie) Fellows Dennis died on April 13, 2024 after a period of declining health. She was born on May 6, 1936 in Lebanon to He... remainder of obit for Winnifred Rae Dennis

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Enterprise: Business and nonprofit announcements

Enterprise: Business and nonprofit announcements

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show