Column: Is anyone truly a native of anywhere?

| Published: 03-30-2019 10:20 PM |

Last month I wrote a piece for the Valley News called “Snow labors; or, becoming a Vermonter.” Not surprisingly, a few emails arrived attempting to educate me about who can be called a Vermonter. All good-natured, they were written by people who had been born here and whose parents and grandparents had been born here.

Apparently, one cannot become a Vermonter. One must be born here of Vermont natives.

How many generations does it take to be a native Vermonter? If the logic behind the joke works and kittens born in an oven are not biscuits, then kids born in Vermont are not necessarily Vermonters. Will their children then be, or will they have to wait for grandchildren to finally have offspring that make the native grade?

Folks who move to Vermont or who buy a second home here are referred to as flatlanders. Politicians who come here to run as Vermonters are referred to as carpetbaggers. “Flatlander” sounds negative to me, as if one was pulled up off a two-dimensional surface like Gumby. “Carpetbagger” brings back images of slick politicians carrying cheap carpet-sided suitcases, riding into the south bringing radical Republican ideals of Reconstruction.

The biggest problem with calling people from away flatlanders is it assumes they all come from places with minimal slope.

I refuse to be called a flatlander, as I hail from southeast Missouri’s St. Francois Mountains, the most ancient granitic pluton in the country. I’ve hauled buckets of water up those Precambrian mountains and raised goats on the side of what remains of them after 1.4 billion years of erosion. I might not ever be a native Vermonter, but surely, riding bareback over those thousand-foot hills counts for something.

But wait — am I even a native Missourian?

Going back a few generations I find German, Bavarian and Prussian great-great-grandparents arriving in the mid-1800s, seeking fertile land and religious freedom. They settled near English ancestors who had come to Missouri by way of Maryland, where they settled in the 1600s with Lord Calvert, again searching for religious freedom and arable land.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

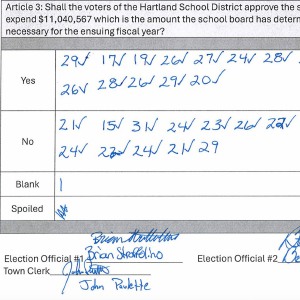

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

After a hundred years in Maryland, things again became dicey for Catholics, and they found themselves once more on the move, settling down on the fertile river bottoms of southern Missouri. Three German brothers married three English sisters. One of those couples became my great-grandma and great-grandpa.

Dad’s side was Irish and English, city folk who came during the great famine. They tried making a life in California, where dad was born, but returned to St. Louis to run a Goodyear tire shop; one uncle became a plumber, the other gave up plumbing to become an infamous gangster, dying at the wrong end of a machine gun.

I am not a Vermonter then, not having been here long enough; not a Missourian, having left the Midwest; not German nor English nor Irish. Maybe “mish-mash Northern European” might be my moniker. Or, tracing my genetic trail back 2 million years, I might find I am a native of one place, Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, a distinction I share with 7.5 billion other humans. Religious traditions differ, but science says we may all claim East Africa as our ancestral home — Europeans, Asians, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders — all humans, all cousins, all natives of one place.

In botany, we refer to native plants as those from the same continent that shifted as the glaciers retreated. Non-native plants evolved on different continents and came to their new home on vessels. A non-native can become naturalized after being somewhere long enough and not showing aggressive tendencies, like Queen Anne’s lace.

Invasive plants are those non-natives that take advantage of their unique adaptive strategies and lack of natural predators to outcompete native species. Beech trees are natives that came north after glacial retreat. Coltsfoot is non-native, yet because it has been here a long time, is valued for medicinal properties and is pretty, it is not usually considered invasive. Japanese knotweed, however, is highly invasive, for it comes up early, persists through a deep root system, and destroys riverine habitat.

Perhaps Vermont needs a similar classification system for people:

■ Natives: third generation or longer.

■ Non-native-naturalized: second generation; does no harm.

■ Non-native: first generation or less; does no harm.

■ Invasive: comes to Vermont for profit, greed and destruction.

Micki Colbeck, of Strafford, is an artist, a conservation biologist and a member of the Strafford Conservation Commission. Write to her at mjcolbeck@gmail.com.

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read