Column: Megachurches reach beyond evangelicals

| Published: 12-03-2022 10:00 PM |

As someone who studies religion in North America, I’m often asked if there are any non-evangelical megachurches. The answer is an emphatic yes. I recently spent a Sunday at one, St. Andrew United Methodist Church, in the suburbs of Denver.

Many scholars (somewhat arbitrarily) define megachurch as a congregation that draws 2,000 or more worshippers every week. Although a case could be made for Moody Church in Chicago, I typically cite Angelus Temple, in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, as America’s first megachurch.

Opened to the public on New Year’s Day, 1923, Angelus Temple was a marvel, the creation of famous Pentecostal evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson. The design couldn’t be more different from traditional, cruciform churches. It was circular with a large stage in front, signaling that this space was suitable for entertainment.

McPherson obliged, conscious of the fact that she was competing with Hollywood across town. She produced theatrical sermons, dressed one time as a traffic cop astride a motorcycle, to capture the congregation’s attention.

Subsequent megachurches have imitated Angelus Temple. Willow Creek Community Church, northwest of Chicago, set the standard for megachurches late in the 20th century. Founded by Bill Hybels, Willow Creek also adopted the auditorium configuration and opened its services with music and dramatic skits.

The other standard feature for evangelical megachurches is so-called praise music.

This is typically initiated by a “worship team” — guitars, keyboard, drums and several vocalists — who seek to create a worshipful mood with soft, lilting congregational singing. One tune segues seamlessly into the next, and sometime toward the conclusion of the second song the vocalists lift their foreheads toward the ceiling, eyes closed, one hand in the air (the other clutches the microphone), a pained expression on their faces, which I expect is meant to signal devotion.

I find the whole routine emotionally coercive, but apparently it works. Although religious adherence, even among evangelicals, has declined over the past several decades, evangelical megachurches still dot the countryside. Evangelicals, after all, almost instinctively know how to speak the idiom of the culture, whether it be the open-air preaching of George Whitefield in the 18th century, the circuit riders and colporteurs of the 19th century, the urban revivalists of the 20th century or mega-churches of more recent vintage, with their airport-style parking lots and their food courts modeled on suburban shopping malls.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

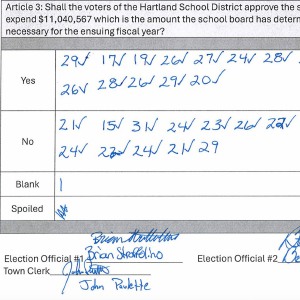

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Some mainline (that is, non-evangelical) Protestants have sought to replicate that model, and St. Andrew, with a commanding view of the Rocky Mountains, has succeeded remarkably well. Thousands pass through its campus every week, and the church offers a variety of programs, everything from Spiritual Seekers and Understanding the Old Testament to Women’s Spiritual Growth Group and Rebuilding When Your Relationship Ends Seminar.

A kiosk in the lobby invites visitors to sign up and collect a gift — or as the cosmetic counters in department stores advertise, a “free gift.” Congregants then drift into the auditorium-style worship space for one of the three Sunday services. As they settle in, a large jumbotron screen, ubiquitous in megachurches, loops through reminders and announcements about coming events.

When the music starts, the difference between mainline and evangelical megachurches becomes apparent. Instead of a worship team, St. Andrew has a bell choir, a huge, robed choir and an orchestra, complete with brass, woodwinds, timpani and a bass drum. The sound is full and glorious, and the effect is beckoning rather than coercive; the only false note (pun intended) was the applause, a regrettable habit borrowed from white evangelicals, one that underscores the misconception that church music skews more toward entertainment rather than worship.

The opening prayers and call to worship, led by an associate pastor (a woman), struck me as a tad ponderous, but that tends to be the case among mainline Protestants who share with evangelicals a weakness for the cult of novelty, believing that they need to come up with new material every week. (That critique, you understand, comes from an Episcopal priest who believes that it’s tough to improve on the timeless prayers and cadences in the Book of Common Prayer.)

Similar to evangelical megachurches, the culmination of the service at St. Andrew is the sermon, delivered on this Sunday by the senior pastor, Mark Feldmier. Dressed in a black cassock with a green stole, Feldmier stood on stage without a pulpit. He is a superb preacher, biblically literate with a folksy demeanor. As he wove through his homily, I was astounded at the felicity of his delivery. He conceded later that he was working from teleprompters; nevertheless, the pastor’s sermon was very impressive, and he apparently spends 10 to 12 hours a week in preparation.

St. Andrew is a refreshing exception to the larger trends in American Protestantism.

Every week I hear or read about churches merging with other struggling congregations, repurposing their spaces as restaurants or coffee houses or simply closing their doors.

At a time when religious adherence is fading and church attendance lagging, many congregations face difficult choices. If trends continue, we are looking at the survival of the fittest. Evangelicals, however, no longer have a monopoly on megachurches.

Mainline congregations, as St. Andrew in Colorado demonstrates, are adapting to changing cultural circumstances as well.

Randall Balmer, an Episcopal priest, is the John Phillips Professor in Religion at Dartmouth College.

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read