Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

HANOVER — One of Susanne and Half Zantop’s two daughters said Thursday that she tries to “compartmentalize” her personal grief over the loss of her parents from her attitude about the fate of James Parker, who was paroled on Thursday after serving the...

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

CONCORD — A man who has served more than half of his life in prison for his role in the 2001 stabbing deaths of two married Dartmouth College professors as part of a plan to rob and kill people before fleeing overseas was granted parole Thursday.James...

Sports

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

As surely as snapping the finish-line tape signifies a winner, the Upper Valley is filled with high school track and field potential this spring.A number of area schools won outdoor titles last year, and some followed that up with indoor successes...

Thetford tops Windsor in 19-18 softball slugfest

Thetford tops Windsor in 19-18 softball slugfest

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Windsor baseball’s annual gauntlet begins with Hartford defeat

Windsor baseball’s annual gauntlet begins with Hartford defeat

Opinion

A Yankee Notebook: An inevitable and terminal move

Living three and a half hours apart, as we do, my dear friend Bea and I get to see each other about every two weeks or so, on average. This is almost without doubt an ideal arrangement, as our lifestyles are quite different, and neither of us could...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

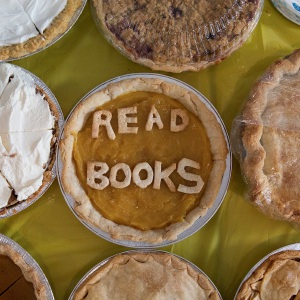

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Acoustic music jam in White River Junction

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Stocking Windsor’s Kennedy Pond

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Quechee Gorge Bridge construction begins

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Getting a lift in South Royalton

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Lebanon’s reconstruction project

Arts & Life

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

For much of its history, JAG Productions, the small, White River Junction theater company that specializes in telling stories from deep inside the black, queer, American experience, has had to be nimble. Company founder Jarvis Antonio Green has...

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Art Notes: The Pilgrims to perform ‘last’ show Saturday in Hanover

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Upper Valley residents witness total eclipse

Obituaries

Douglas G. Whitcomb

Douglas G. Whitcomb

Hartland, VT - Douglas G. Whitcomb, age 84, passed Wednesday, February 21, 2024. Services will be held in The Vermont Veterans Memorial Cemetery Chapel in Randolph Center, VT, on Friday... remainder of obit for Douglas G. Whitcomb

Edward Peter Rogenski

Edward Peter Rogenski

Newport, NH - Edward Peter Rogenski 11/10/1938 - 03/28/2024 Edward Peter Rogenski better known as Pete passed away peacefully at his home in Newport New Hampshire. He was 85 years old.... remainder of obit for Edward Peter Rogenski

Harold Graham

Harold Graham

Woodsville, NH - Harold "Jack" John Graham, 95, passed away at his home on Monday, April 15, 2024, with family at his side. He was born in his family home on Savage Hill in Lisbon, NH on No... remainder of obit for Harold Graham

Lisa Gurney

Lisa Gurney

Newbury, VT - Lisa Marie Gurney, age 55, passed Thursday, March 7, 2024. There will be a graveside service on Thursday, May 2, 2024, at the New Oxbow Cemetery in Newbury, VT, at 10 AM. ... remainder of obit for Lisa Gurney

2024 Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse guide

2024 Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse guide

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes

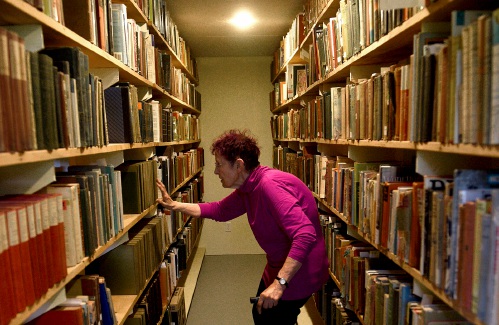

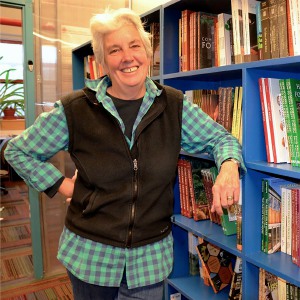

Town Meeting 2024: Previews and results of Upper Valley meetings and votes A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’

A Life: Priscilla Sears ‘was bold enough to be very demanding’ Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford

Kenyon: Dismas House celebrates 10 years of fresh starts in Hartford Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Editorial: Accounting can now begin in Claremont police case

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show