Latest News

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

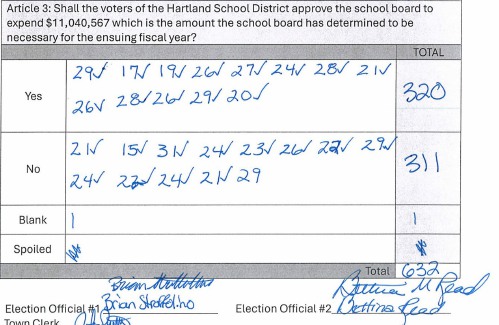

HARTLAND — The School Board is preparing to warn a budget vote for the third time this year after a successful petition by residents to hold another round of balloting.On April 2, voters narrowly approved an $11.1 million school budget by a vote of...

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions, the White River Junction theater company that has championed the work of Black, queer and trans artists, announced last week that it is closing in June after eight years of bringing groundbreaking work to the Upper Valley.Jarvis...

Most Read

Upper Valley winter shelters kept dozens warm and dry

Upper Valley winter shelters kept dozens warm and dry

Former principal of South Royalton School released from prison

Former principal of South Royalton School released from prison

Owner of Friesian horse facility ordered to pay care costs for seized animals

Owner of Friesian horse facility ordered to pay care costs for seized animals

Editors Picks

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Kenyon: Hanover stalls on police records request

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Sports

Woodstock boys lax defense steps up, holds off Hartford

WHITE RIVER JUNCTION — Monday night’s boys lacrosse game between host Hartford High and Woodstock came down to the final minute, with the Wasps prevailing, 11-10.The Vermont inter-division clash might have been decided, however, by a pair of goals at...

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

Opinion

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Hey, Major League Baseball, does the name Pete Rose ring a bell? Remember him, “Charlie Hustle”? One of the game’s greatest players, whom you banned for life in 1989 because he bet on baseball games?We ask because you have on your hands another...

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

A Yankee Notebook: Among the crowds on vacation out West

Photos

Clear and free in Hartford

Ramping up their foraging

Ramping up their foraging

Roadside assist in Bethel

Roadside assist in Bethel

Preserving habitat in Etna

Preserving habitat in Etna

Pitching in

Pitching in

Arts & Life

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

Before Hurricane Katrina hit her newly adopted city of New Orleans in 2005, Trish O’Kane knew next to nothing about the environment — let alone birds.O’Kane had spent much of her life working as an investigative human rights journalist in Central...

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Obituaries

Kenneth A. Curtis

Kenneth A. Curtis

West Lebanon, NH - Kenneth A. Curtis, age 64, passed Monday, April 15, 2024. A graveside service will be held 11am in the West Lebanon Cemetery on Thursday, May 2, 2024. Knight Funeral Home in White River Junction has been entrusted... remainder of obit for Kenneth A. Curtis

Delores Howe

Delores Howe

Delores "Dee" Howe Hinesburg, VT - With the final lyrics of "King of the Road" wafting in the springtime air, our beloved Delores B. Howe crossed into the loving hands of our savior to reside in that spiritual mansion, that house not mad... remainder of obit for Delores Howe

Jane Elizabeth Rooney

Jane Elizabeth Rooney

Manchester, NH - Jane Elizabeth Rooney, who had a long career as a social worker and psychotherapist, died on March 28, 2024, at Mount Carmel Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in Manchester, NH. Jane was born in Framingham, Massachuset... remainder of obit for Jane Elizabeth Rooney

Cory John MacElman

Cory John MacElman

Lebanon, NH - Cory John MacElman, age 39, passed Friday, April 19, 2024. Ricker Funeral Home of Lebanon, NH is assisting the family. ... remainder of obit for Cory John MacElman

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Local Roundup: Hartford girls lacrosse gets decisive win over Colchester

Local Roundup: Hartford girls lacrosse gets decisive win over Colchester

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show