Amid the budget back and forth, fate of NH’s most vulnerable hangs in the balance

| Published: 05-16-2023 2:13 PM |

Gov. Chris Sununu sent the House a budget in February that upped spending significantly over his last one, with a notable increase for Medicaid beneficiaries and other vulnerable populations that advocates say aren’t getting the services they need.

The House increased spending even more, to nearly $15.9 billion over two years, an 18 percent increase over the prior budget. As the Senate takes up the House’s budget, advocates will be watching to see which investments survive — and what House cuts may be reversed.

Monday, Senate President Jeb Bradley, a Wolfeboro Republican, submitted an amendment reinstating Sununu’s $1.4 million Northern Border Alliance Program to enhance patrols along the Canadian border. In a second amendment, he proposed removing public notice of immigration checkpoints, a measure the House had included in its budget.

There are signs of agreement on some things, such as longer postpartum care for low-income women, increased child care assistance, a 12 percent pay raise for state employees over two years, and an increase in Medicaid rates.

Though updated revenue estimates give the Senate an additional $184.3 million to work with, according to the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, expect changes.

Here are seven things to watch.

The workforce shortage that’s walloped business owners and state agencies hasn’t spared social service providers, who say they can’t hire because they’re getting too little in Medicaid funding from the state. They’ve asked for a $200 million increase to fill vacancies, necessary they say to expand services.

Sununu included $24 million in his budget. The House boosted that to about $134 million. A Senate bill has allotted much less, $80 million, an amount advocates will push the Senate Finance Committee to increase by sharing the kinds of stories they told the Bulletin earlier this year.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

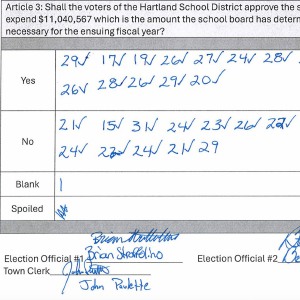

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

New Hampshire’s 10 community mental health centers, which rely on Medicaid for 70 percent of their funding, have nearly 340 clinical vacancies as they are seeing their wait lists grow at a time when anxiety, depression, and other mental health needs have increased.

It’s the same story for agencies hired by the state to give people who qualify for nursing homes services to remain at home instead through the Choices for Independence program. Those agencies are paying $13.50 an hour, and that’s with fundraising to make up for insufficient Medicaid payments from the state.

Unable to fill openings, they are increasingly turning people away and cutting back on client services, a combination they say could drive more people to nursing homes, a far more expensive option for the state.

Other providers, from midwives and substance disorder treatment centers to assisted living facilities, are joining the mental health centers and CFI providers in seeking more in Medicaid rates. Only the state’s hospitals would not see an increase, at their request, to allow other providers more.

Whatever the state spends on Medicaid rates will be at least matched by the federal government.

Granite Advantage, the state’s expanded Medicaid program implemented in 2014, has been credited with reducing the number of uninsured residents, improving health outcomes, saving the state’s hospitals millions of dollars, and saving taxpayers money.

Advocates say it’s an especially good deal for the state because the federal government pays for most of the cost, 90 percent. The program is slated to end this year unless lawmakers continue it. It looks all but certain they will, but House and Senate lawmakers sharply disagree over how long.

The House included a two-year extension in its budget. There is bipartisan support in the Senate to continue the program without an expiration date, a position favored by advocates.

The program provides Medicaid insurance to low-income people between 18 and 64 ineligible for regular Medicaid because they don’t meet the program’s requirements: Beneficiaries must have a physical or developmental disability or be caring for children or other family members. A person must earn no more than 133 percent of the poverty level. That would equal about $33,000 or less a year for a household of three.

The state expects about 64,000 will qualify once it reviews eligibility for those who qualified during the pandemic. Enrollment reached 95,000 during the pandemic.

Postpartum care will likely be extended from 60 days to 12 months, something more than 30 other states have done.

The House included that extension in its budget, and the Senate has indicated support to do the same. Senate Bill 175, dubbed the MOMnibus bill, would go even further by providing Medicaid coverage for donated breast milk, lactation services, and doula care during and after delivery. The bipartisan bill includes about $1.1 million to begin those services in the second year of the budget.

The bill’s prime sponsor, Sen. Becky Whitley, a Hopkinton Democrat, is optimistic.

“I really do think it’s not a big fiscal impact when you look at the impact on improved health outcomes and for working families,” she said. “I think it’s just smart policy that a lot of people really came together on.”

More students could take advantage of free and reduced-price lunch under two provisions of the House budget.

Currently, those meals are available to families making up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level if a parent or guardian submits a complex application that requires significant income information. Many who’d be eligible don’t apply.

The House removed that hurdle in its budget with a federal program that automatically enrolls students whose families are on Medicaid. The Senate has passed its own direct certification bill but hasn’t decided whether to include funding it in its budget.

Phil Sletten, research director of the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute, noted that “direct certification” doesn’t increase who is eligible for free or reduced-price lunch but would likely lead more students who are already eligible to take advantage of the benefit.

A second effort would expand access, Sletten said, by making subsidized meals available to families who earn up to 300 percent of the federal poverty level, about $74,600 a year for a household of three. Currently families can earn up to 130 percent of the federal poverty level to qualify for free school lunch and up to 185 percent for reduced-price lunch. That group would have to complete the application process to participate.

Sletten said recent census data showed that between June 2022 to April 2023, an average of 15,700 Granite Staters each month said they weren’t working because they were caring for a child not in school or child care. March’s 2.4 percent unemployment rate translated to about 18,800 people.

“It’s not as though 15,700 people would (immediately) be in the labor force,” Sletten said, “but if 15,700 people were to suddenly re-enter the labor force, then that would be a significant increase relative to the number of people who are unemployed.”

Both chambers would tackle the shortage of child care, but differently.

In the House budget, more families would qualify for the state’s child care scholarship money through an increase in income limits, from 220 to 250 percent of the federal poverty level to 85 percent of state median income. That would increase the threshold from $50,600 to $57,600 annually for a family of three to about $86,200. The Senate is considering the same increase in its budget.

The House would also increase reimbursement payments for child care providers that serve families receiving scholarships, a measure the New Hampshire Fiscal Policy Institute said could allow providers to hire more staff and expand access to child care. The Senate has supported doing the same with Senate Bill 237.

But that bill would go further with an investment of $17 million over two years for scholarships, provider rates, a new child care workforce development program, and money for community college system scholarships to support early childhood education programs.

The governor and House included funding for two initiatives in their budgets to expand housing. But the House made key changes to Sununu’s proposal.

He included $25 million for grants to encourage the development of affordable housing, to be overseen by the New Hampshire Housing Finance Authority. The House increased that to $30 million.

Sununu also sought to add $30 million to InvestNH, a separate housing fund he created last year with $100 million in federal pandemic assistance. The House budget cuts that to $15 million and makes changes Sletten called significant. The program currently provides grants to developers and municipalities. The House budget limits grants to the latter.

The Senate is considering similar housing legislation.

Senate Bill 145 would spend $29 million to encourage workforce and other housing, most of it through grants available to municipalities. Senate Bill 231 would invest $45 million in expanding workforce and affordable housing as well as shelter programs addressing homelessness.

The bill includes tax credits to encourage the development of new housing in historic buildings, something the House eliminated from Sununu’s proposed budget.

The “Coalition for a People’s Budget,” a broad group of advocacy groups, including the New Hampshire Council of Churches and state chapter of the American Friends Service Committee, has asked the Senate to stick with its proposal.

Sununu and federal authorities have said illegal border activity has increased substantially since the pandemic, creating a need for enhanced border patrols. But neither state nor federal officials have been willing to provide numbers demonstrating the scope and nature of those increases. A U.S. Customs and Border Protection spokesperson told the Bulletin it does not track incidents in New Hampshire, which shares a 58-mile border with Canada.

Bradley’s amendment reversing the House’s elimination of the Northern Border Alliance Program would leave its oversight to the Department of Safety.

The House budget eliminated $40 million for a new men’s prison in Concord, a project Corrections Commissioner Helen Hanks said is necessary to add basic security features, replace windows that don’t open, and create a space conducive to a rehabilitative environment.

The authors of the “people’s budget” are urging senators to follow the House’s lead, saying the state should instead focus on reducing incarceration.

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination