A Life: Hilda Weyl Sokol; ‘Something about the sciences … intrigued her’

| Published: 03-13-2023 3:50 PM |

HANOVER — Growing up, Dr. Hilda Weyl Sokol’s children associated her career with rats.

Her son, Niels Sokol, and her oldest daughter, Kirstin Sokol, remember taking trips to pick up rats. One, nicknamed Snow White, even became a pet to Sokol’s youngest daughter, Heidi.

Niels Sokol would go with his mother to pick up rats from the Lebanon Municipal Airport, where he would take the crates resembling lobster traps and move them into Sokol’s car. The animals were a vital part of Sokol’s research at Dartmouth Medical School, where she worked in the physiology department as a teacher and researcher.

“I remember she’d come home from work some days and her hands would be stained in black,” Niels Sokol recalled in a recent Zoom interview with his siblings. Sokol spent hours cutting rats’ brains to locate the pituitary gland, her area of study as an endocrinologist.

Sokol died on Nov. 2, 2022, at age 93 at Kendal at Hanover. When she joined the faculty at Dartmouth Medical School in 1961, she was one of a handful of women instructors at Dartmouth College and its graduate schools. Women were first admitted to the medical school — now known as the Giesel School of Medicine — in 1960, a dozen years before women were admitted to undergraduate programs.

“When they came up here, they felt that they were immigrants to this area, which was definitely a male bastion,” said Bernie Benn, whose late wife, Vivian Kogan, a French literature professor, joined Dartmouth’s faculty in the late 1960s. “Women tended to bond together.”

Sokol and her late husband, Robert Sokol, moved to Hanover from the Boston area. The couple met as kids at a northern New Jersey camp for families involved in the socialist movement. That belief system — which promoted equality — stayed with the Sokols for the rest of their lives. Sokol was a strong feminist who advocated for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and, though she used her husband’s last name, her signature always included Weyl.

For “Mom, having kept her middle name, was an important mark,” Heidi Sokol said. “What we delighted (in) … was when a student would call the house and say, ‘Is Professor Sokol there? Is Dr. Sokol there?’ and we would just delightfully say, ‘Which one?’ ”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

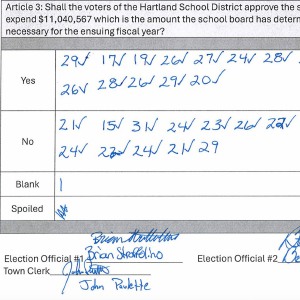

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Sokol graduated from Hunter College in New York City, where she was raised, and earned her doctorate from Harvard College in 1956.

“Five days before I was born, she defended her dissertation,” Kirstin Sokol said.

In a 1984 interview with the Valley News, Sokol said she didn’t feel discriminated against while she was in graduate school.

“I did the work, and I assumed I’d get accepted,” she remarked.

But when she entered the workforce, that started to change: “It was always said that Harvard trained a lot of women but never hired them.”

The couple both taught in the Boston area while Robert Sokol was finishing up his doctorate at Columbia University in New York City, which he earned in 1961.

One of the reasons the Sokols ended up at Dartmouth is because the college was one of two that offered jobs to both of them. Robert Sokol joined the college’s sociology department at the same time Hilda Sokol joined the medical school’s physiology department. The couple had agreed they’d only go to a university that had jobs for them both.

“Mom’s credentials, it was hard for people to reject her,” Heidi Sokol said. “How many PhDs from Harvard are you getting as an opportunity hire? Not many. Those fields were difficult for women, and it wasn’t easy for her.”

At Dartmouth, the couple became involved in the movement to admit women. Robert Sokol did a survey at the college where men expressed fears that their grades would drop if women were admitted. That turned out not to be the case, Sokol recalled in the 1984 interview about a 1982 ceremony honoring the 10-year anniversary: Men’s grades went up, and they studied more.

“Dartmouth’s treasurer at the time commented that the bottom line would be whether women graduates supported the college as generously as men,” according to the article. “Hilda retorted that that would depend on whether Dartmouth women were hired to the same caliber jobs as Dartmouth men.”

At Dartmouth, Sokol worked part time when her children were young.

“There was something about the sciences that intrigued her, that fit her need for order … need for explanation,” Kirstin Sokol said, noting her mother’s fondness for the scientific method. “That kind of inquiry worked with her brain.”

Enter the Brattleboro, Vt., rat. It was discovered in 1961 at the Brattleboro lab of Dr. Henry Schroeder, a physiologist at Dartmouth Medical School.

“A very astute technician of his noticed that one cage of rats was always wet,” said Dr. Charles Wira, who was a student of Hilda Sokol’s before becoming her colleague at the medical school. Initially, the wet cage was thought to be due to a leaky water bottle. “It became very clear that it wasn’t; it had to do without the amount of water these animals were ingesting.”

Sokol and her colleague, Dr. Heinz Valtin, received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the rat from 1964 to 1982. The pair set out to find out why, exactly, the rats were ingesting so much water. They discovered that the rats had “Diabetes insipidus,” a condition where the pituitary gland does not have vasopressin, a hormone whose absence caused the “unbelievable thirst that these animals had,” Wira said.

“That discovery, and the initial work that Heinz and Hilda did, led to this rat being used all over the world,” Wira said. Those rats “have had important applications in the field of not only endocrinology but cardiology, pharmacology, psychology, as well as been used for studies of blood pressure, alcoholism, some types of cancer, memory and aging.”

Their book, “The Brattleboro Rat,” was published by the New York Academy of Sciences in 1982.

In 1981, Sokol and Valtin organized a four-day symposium at Dartmouth that included 150 scientists from around the world. They also shared — and shipped — the rats to scientists all over the world so that they could use them in their research.

“What Valtin and Sokol did was epitomize the spirit of international exchange of scientific information,” Wira said. “They shared them with other laboratories that were interested in much more than the changes in the loss of vasopressin. As a result, they became very valuable in many other areas.”

Sokol thought of herself as a teacher first and a researcher second. Wira described her teaching style as natural and conversational.

“She loved to engage students in questions and answers,” he said. She mentored female students and encouraged them to pursue careers in STEM.

In addition to the medical school, Sokol taught courses in the college’s women’s studies department. A freshman seminar class she taught was titled “Reproductive Technologies: Biological Aspects and Social Implications.”

Both Sokol and her husband worked hard to balance their professional careers while raising their three children. Sokol insisted that the family eat breakfast together every morning — and everyone had to be dressed for the day. She prepared balanced and healthy meals, including a glass of orange juice each morning so the kids would get their Vitamin C.

“In our house if you needed something medical like a Band-Aid or you weren’t feeling well … you went to Mom,” Kirstin Sokol said. “If you had an emotional day or you had something that happened to you at school that hurt your feelings, you went to Dad.”

After Sokol retired as a professor in 1995, she joined Dartmouth’s Semester at Sea program, teaching students while exploring the world. In 1999, the Hanover Democrats recruited her and Benn to run for two seats in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. Sokol served three terms, from 2000 to 2006, before choosing not to run for re-election.

“Hilda was a very interesting person in that she gave a demeanor of being quite moderate but, in fact, she was really quite left and she spoke her mind with force,” said Benn, who would often drive to Concord with Sokol.

She advocated for a higher minimum wage, more funding for education, universal access to health care and reproductive choice. The Democrats were in the minority when Sokol served, which frustrated her, Benn recalled. But she never shied from speaking her mind.

“She was someone who enjoyed — and had the energy — to be an activist,” Benn said.

Editor’s note: Sokol’s family will be holding a celebration of life for her at 2 p.m., Saturday, April 1, at Kendal at Hanover. Liz Sauchelli can be reached at esauchelli@vnews.com or 603-727-3221.

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’