Crowd turns out to honor late Ascutney Fire Chief Darrin Spaulding

WEATHERSFIELD — An estimated 1,500 people filled the Weathersfield School gym for a funeral for Ascutney Fire Chief Darrin Spaulding on Saturday.Among those attending were Spaulding’s family members, firefighters in uniform, and others wishing to pay...

Pick a sport and Pete DePalo’s has probably officiated it over the past 40-plus years

Pete DePalo spent his first 15 years living on Coney Island in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, home of America’s first large-scale amusement park. His family moved to the Upper Valley and his life since has been filled with games.Soccer games....

Sports

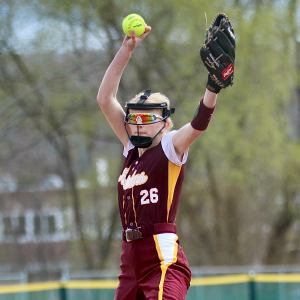

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

When it comes to Upper Valley high school softball, one program stirs the proverbial championship drink.In three years under coach Chuck Simmons, Oxbow High has reeled off 49 wins in 53 games and raced relatively unimpeded to state honors each time....

2024 Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse guide

2024 Upper Valley high school girls lacrosse guide

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

2024 Upper Valley high school track and field guide

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

2024 HS boys lacrosse guide

Opinion

A Yankee Notebook: An inevitable and terminal move

Living three and a half hours apart, as we do, my dear friend Bea and I get to see each other about every two weeks or so, on average. This is almost without doubt an ideal arrangement, as our lifestyles are quite different, and neither of us could...

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

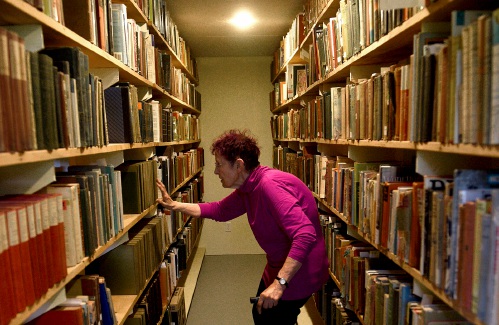

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Column: The age-old question of what to read

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Editorial: Transparency wins in NH Supreme Court ruling

Photos

Preserving habitat in Etna

Pitching in

Pitching in

Picture day prep

Picture day prep

Helping a good cause in Etna

Helping a good cause in Etna

Spring cleaning

Spring cleaning

Arts & Life

How a hurricane and a cardinal launched a UVM professor on a new career path

Before Hurricane Katrina hit her newly adopted city of New Orleans in 2005, Trish O’Kane knew next to nothing about the environment — let alone birds.O’Kane had spent much of her life working as an investigative human rights journalist in Central...

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Out & About: Vermont Center for Ecostudies continues Backyard Tick Project

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Over Easy: Marvels in the heavens, and in the yard

Obituaries

Russell Haviland

Russell Haviland

West Newbury, VT - Russ Haviland passed away peacefully in North Haverhill, New Hampshire on April 18, 2024. He was born on March 17, 1941, in Brattleboro, Vermont to E. Randall Haviland and Gretchen (Shaw) Haviland. Russ's time was a l... remainder of obit for Russell Haviland

Constance Barth

Constance Barth

Brownsville, VT - Constance Rae Zullo Barth passed away April 21, 2024. She was 81. The world is significantly less without her and infinitely more for the gifts her life brought us. Born August 31, 1942 in Claremont, New Hampshire, ... remainder of obit for Constance Barth

Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Adrian W. Frary, Jr. Tunbridge, VT - Adrian W. Frary, Jr., age 98, passed Wednesday, April 3, 2024. A graveside memorial service for Adrian will be held Sunday, April 28, 2024 at 2pm with refreshments and fellowship to follow at the Roy... remainder of obit for Adrian W. Frary Jr.

Elaine J. George

Elaine J. George

White River Jct., VT - Elaine Jane (Viens) George passed away April 21, 2024, surrounded by her loving family and friends. Elaine was born on Dec. 12, 1934, in Springfield, Mass., the ninth child of George and Delima (Ashline) Viens, Sr... remainder of obit for Elaine J. George

Former principal of South Royalton School released from prison

Former principal of South Royalton School released from prison

Upper Valley residents among advocates for NH aid-in-dying bill

Upper Valley residents among advocates for NH aid-in-dying bill

NH man convicted of killing daughter, 5, ordered to be at sentencing after skipping trial

NH man convicted of killing daughter, 5, ordered to be at sentencing after skipping trial

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Lebanon girls lacrosse prevails over Coe-Brown

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

Local roundup: Lebanon softball sweeps wins from Souhegan, Stark

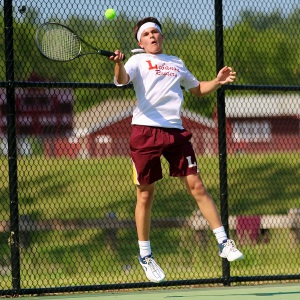

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

2024 Upper Valley high school tennis guide

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’

A Life: For Kevin Jones ‘everything was geared toward helping other people succeed’ Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show

Amid financial difficulties, Lebanon-based Revels North cancels midwinter show