Hartford Christian Camp Eyed for Historic Designation

| Published: 04-25-2016 12:45 AM |

White River Junction

To the Rev. Michael Gantt, who walked the 7 acres of grounds off Advent Lane on Thursday, the Advent Camp Meeting Grounds is a place where people have met, fallen in love, gotten married and been laid to rest, all in the service of a higher power.

“When spring comes and the flowers bloom, this is the most beautiful place in the world,” he said.

The camp, which was founded in 1887 and has been operating continuously ever since, has local and state historic preservationists excitedly working to get it entered into the National Register of Historic Places.

The buildings have their own special, rustic charm.

In a residential lodge, the locks on the doors consist of blocks of wood rotating around nails. Many of the rooms are equipped with what Gantt calls “thunder pots,” a necessity before a toilet was installed in a small room downstairs, beneath a sign that asks “If you were on trial for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?”

One room, with yellow walls and a tan ceiling, is occupied by a Scrabble game; another, with tan walls and a blue ceiling, has a couple of old Norman Rockwell pictures thumb-tacked to the wall.

“You couldn’t build this today,” said Gantt, who has been president of the Advent Christian Church and Conference Center of White River Junction, which owns the property, for 40 years, “It would be illegal.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

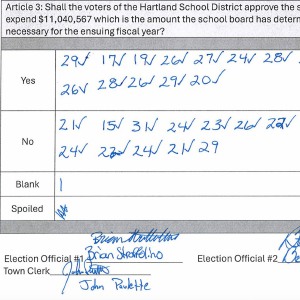

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

That’s because the camp, also known as the White River Christian Camp, consists of 32 cottages and community dwellings made of simple plank board walls and floors topped by corrugated tin roofs, all woefully out of step with modern building practices.

By way of an example, Gantt led the way into the dining hall, which was jacked up off the dirt 25 years ago and set down on a concrete slab. In the far corner of the kitchen, beyond the chest freezer and metal food prep surfaces, sits a stove.

In 2009, Gantt said, an association member decided the stove should be turned 90 degrees so it faced in a different direction.

It was a simple task, accomplished in five minutes, but it had major consequences.

“When the guy from the gas company got here, he said, ‘I can’t touch that,’” Gantt said.

Gantt was dismayed to learn that he couldn’t legally hook up a stove in a building that didn’t meet building codes.

“We were grandfathered,” he said. “Grandfather died.”

It took six weeks and $35,000 to get the building in line with the minimum requirements.

The dining hall is not unique.

A water line servicing a row of recreational vehicles is leaky and in need of repair. In the tabernacle, two of the walls were recently winched into place with cables and come-alongs, and are held in their current positions by giant crisscrossing planks.

Attendance at the camp — while still less than its heyday in the early 1900s, when thousands would come each summer — has grown so much in recent years that the tabernacle can’t accommodate the 275 people who show up for the week-long main event in early August. Some of the campers have been sitting outside the building, struggling to hear the preacher’s words.

To solve that problem, Gantt said, the association plans to expand capacity by popping off one of the walls and moving it outward by about 20 feet, filling in the gaps to complete the addition.

The stove experience, and the fact that most other buildings also are not up to modern standards, underscores the motivation of preservationists to maintain this increasingly rare kind of Christian camp.

“I’m not aware that we’ve documented any other sites like this. That’s why it’s so exciting. Because it’s a different type of resource and community,” said Devin Colman, who has been working with Hartford officials in his role as state architectural historian with the Vermont Agency of Commerce and Community Development.

Colman said that, if the Advent Camp is entered into the National Register as a historic district, it could pave the way for a new category of such recognized communities in the state of Vermont.

“This will inform our understanding of similar properties around the state,” he said. Adding, after a moment, an afterthought: “If there are any.”

Colman said the property’s heritage will help historians and the general public to understand the roots of the religious camp movement, and the ways in which the unique usage shaped the architecture and structure.

“How are they positioned? How are they designed?” he asked. “That informs our understanding of the property as a whole.”

Gantt said the tradition of the week-long Christian camp grew out of the mid-to-late 1800s, when the devout began gathering in the woods for a week at a time in observation of the biblical “Feast of Booths,” during which followers were instructed to “dwell in booths,” typically interpreted as a reference to temporary structures in the woods, “for seven days.”

In 1887, that practice led to the founding of the Advent Camp Meeting Grounds, and the basic idea has remained the same ever since.

Men, women and children gather into bible study groups in the morning. There’s a lot of freedom until the evening.

“When the bell rings for evening meeting, everyone comes together. We meet in the same tabernacle. We stay in the same boarding house,” Gantt said. “It is essentially as it was.”

Gantt and his daughter, Robyn Stires, who has overseen youth programs at the Advent Camp for 40 years, said the transition to a bygone era can bring a culture shock, especially for children.

Stires said that, when the kids are told that their cellphones will be taken away, the collective gasp is so great that it nearly extinguishes the campfire.

But they adjust.

“You drag them down the hill into the camp kicking and screaming because they don’t want to come,” Gantt said. “A week later, you drag them kicking and screaming up the hill because they don’t want to leave.”

Matt Osborn, a Hartford town planner who is coordinating the application, said it will take time to get the Advent Camp listed on the register.

Right now, Brian Knight, a historic preservation consultant from Dorset, Vt., is doing preliminary work by taking pictures, noting the architectural features of each building, and preparing to talk to camp members for an oral history.

Knight was hired by the town with a combination of a $6,400 grant from Colman’s office and a couple of thousand dollars in matching local funds to help support an application to the National Park Service, which curates the National Register.

Gantt and others are likely to talk about a fear — the potential for a fire — that many years ago prompted a change in the camp’s configuration in relation to the packed-dirt loop that runs around its center.

At first, the area was mostly occupied by a series of benches, which would allow two preachers to stand at either end of the green to deliver simultaneous sermons to the large number of congregants. But camp leaders realized that the fire-prone cottages were packed in too close together to protect them from spreading flames. So several of the cottages were lifted onto logs and moved, by horsepower, to their current location in the center green.

Once Knight is done collecting information, he’ll compile a statement of significance and draft a nomination that will be reviewed by the public at a community meeting.

“We would be hoping that the Advent Camp community would support this,” Osborn said, “and if they supported it, the town would likely approve submitting the nomination.”

From there, the application is submitted to the state and, eventually, the federal government.

If the Advent Camp Meeting Grounds is successfully added to the National Register as a historic district, it won’t be the only one in the town of Hartford — far from it, in fact.

The town has roughly 450 buildings included in the National Register — that’s about one for every 10 households counted in the 2010 federal census of the town.

Many of these buildings are located within one of eight historic districts that the town has already established: Downtown White River Junction, Quechee Historic Mill District, Hartford Village, Wilder Village, Jericho Rural Historic District, Christian Street Rural Historic District, the West Hartford Village Historic District and the Terraces Historic District.

In addition to the Advent Camp Meeting Grounds, the Hartford Historic Preservation Commission has a goal of having many more individual buildings and districts entered into the National Register, and would also like to see expansions of existing historic districts considered.

To that end, four years ago, the commission began a two-phase study of its structures.

During Phase One, which was completed in August 2013, a consulting company named Blue Brick Preservation identified 53 properties for individual listing and seven more possible historic districts, with the Advent Camp placed at the top of the list as an “excellent candidate.”

Other possible historic districts were located on Victory Circle, Verna Court, Hartford Avenue, Chandler Road, Mill Road and Old River Road.

During Phase Two, which was completed in December 2015, Lyssa Papazian, a historic preservation consultant hired by the town, identified 13 candidate properties for individual listing and eight more possible historic districts.

A collection of 13 houses in Watson Plaza on Worcester Avenue, a collection of 13 houses on Demers Avenue, and as many as 78 houses in Highland and Manning parks were listed as “high priority.”

The other possible districts are in Frost Park, C-Street, Forest Hill, Chandler Terrace and Christian Street.

Gantt was ambivalent about the prospect of adding the camp to the National Registry.

He didn’t think there would be much material gain, he said, but he also didn’t see how it could hurt, because town officials assured him that the listing wouldn’t put significant restrictions on the camp’s ability to do work on the buildings.

Osborn and Colman both said the listing doesn’t confer any special protections that would limit the camp’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

“The upside is to inform the public that these are important to the community,” Osborn said. “We have a lot of historic buildings and it’s important to the character of the community.”

Colman said the designation helps to leverage grants, and said neither the state nor federal governments play any role in regulating work done on historic properties.

“Usually that has to do with a municipal preservation ordinance,” Colman said. “The real teeth are at the local level.”

Outside of special protections afforded certain buildings in the White River Junction Design Review District, Hartford currently has no building codes that would prevent historic properties from being changed, or even demolished.

The Historic Preservation Commission has recently reviewed demolition ordinances from other communities, and has discussed advocating for a similar ordinance to be implemented in Hartford, according to meeting minutes.

Efforts to reach Jonathan Schechtman, chairman of the Historic Preservation Commission, were unsuccessful.

Gantt said that, regardless of whether the camp receives its designation, he’ll do everything he can to preserve its spirit.

“If I felt like the heritage of this place was under attack, I’d shut it down.”

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling can be reached at mhonghet@vnews.com or 603-727-3211.

]]>

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary

In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary