A Look Back: Crank telephones connected Meriden community for 75 years

| Published: 03-31-2024 5:16 PM |

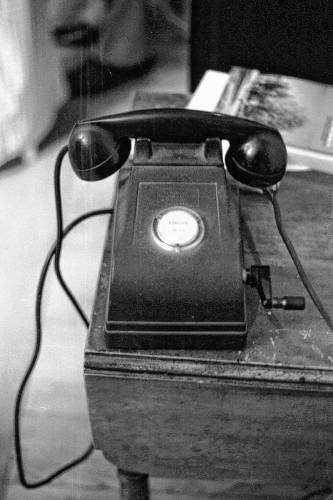

It was a great conversation starter half a century ago, and, if you lived it, the subject can bring amusement, even awe, to those hearing about it today. That’s the “hand crank” or magneto telephone system that served Meriden Village for nearly 75 years.

Meriden Telephone Co. was the last exchange in New Hampshire and Vermont to convert to dial service and the next-to-last in all of New England. A few customers hung on to the quaint crank boxes and wall phones as interior decoration, and they now serve as silent reminders of when a spin of the crank would bring Hazel Chellis on the line to connect the caller to a neighbor or to the outside world via a trunk line to the regional toll center in White River Junction.

The whole enterprise was a Chellis family show. It started when two Chellis cousins went to an exhibit in Springfield, Mass., in 1899 and came home with two phone sets and a roll of steel wire and continued all the way down to the last Chellis, David, who died in 2015. The cousins connected the Chellis farm on — where else — Chellis Road, with a Chellis-run store down the road at the edge of the village.

Soon neighbors became enthralled with this newfangled technology and they were begging to be hooked up, too. Wires would be strung from house to house, farm to farm, along fence posts and roadside trees and in 1904 a switchboard was installed in the Chellis farmhouse to handle the growing traffic.

A couple of years went by and a new Chellis venture appeared, an electric system using a turbine powered by Blood Brook. The stream’s flow soon proved inadequate, so the fledgling Meriden Power and Light Co. ran a line over pastures to connect to the Grafton County Power Co. on Poverty Lane in Lebanon. That necessitated installation of utility poles and overhead lines, work that would occupy Chellis hands almost constantly until the electric business was sold to Granite State Electric Co. in 1948.

When you spin the crank on a crank phone box, you’re turning a tiny armature inside a U-shaped magnet. The electricity thus generated flows to the switchboard where a brass tab flips, telling the operator a caller is waiting. The operator connects the caller with the phone of whomever the caller wants to speak with, and the operator sends an electrical impulse to make the bell in the receiving phone ring.

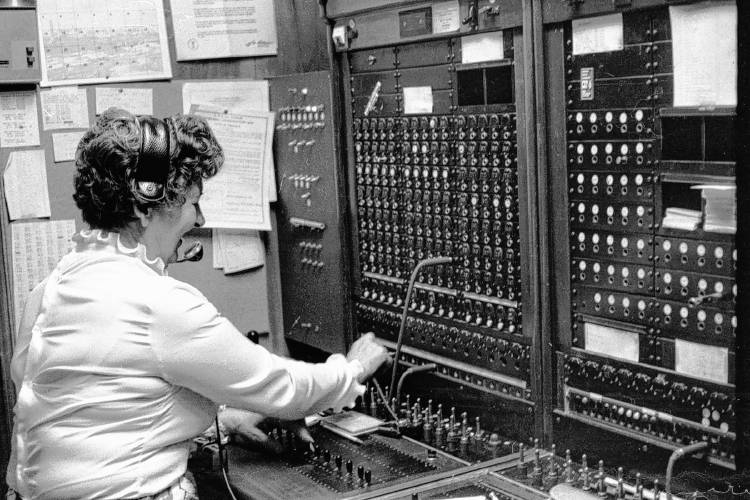

The Meriden Telephone Co. switchboard was in a bedroom in the Chellis farmhouse, tended by an operator 24/7. A bed stood nearby and the operator might be able to snooze a bit between the occasional calls placed in the overnight hours.

As many as eight subscribers might share one of the company’s lines. Thus each location had its own ring, and it could resemble a Morse Code sound if one was not used to it. So many customers sharing one circuit required courtesy — keep your conversation short so another can make their call. And there was little to no privacy, as “listening in” was a favorite pastime of snoops and nosy busybodies on party lines.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Lebanon moves forward with plans for employee housing

Lebanon moves forward with plans for employee housing

Colby-Sawyer president announces plan to depart

Colby-Sawyer president announces plan to depart

Windsor man who failed to show up for trial arrested in Hartland

Windsor man who failed to show up for trial arrested in Hartland

Harold Chellis ran the Meriden Telephone Co. for three decades, then his sons Howard and Frank carried on, and then Frank’s sons Mike, Tom and Dave were linemen, repairmen and troubleshooters beginning when they were Lebanon High School students in the 1960s. Howard’s wife Hazel pulled endless shifts at the switchboard, backed by several local women over the years, and it wasn’t uncommon to hear Howard’s voice handling traffic. Hazel prepared the monthly bills, all in a perfect hand worthy of an architectural plan.

The family enterprise would eventually grow to some 300 subscribers and by the 1960s the volume of calls was expanding rapidly. Kimball Union Academy was the biggest customer, with students calling home and summertime conferences of scientists at KUA stressing the capacity of the few trunks to the White River Junction long-distance hub. A call anywhere near to Meriden — Lebanon, Plainfield, West Lebanon, Claremont — was a 10-cent toll call for the first three minutes.

The Chellis family reached a decision to sell the franchise to a company with the resources to upgrade equipment and operations, and it was acquired by TDS Telecom, a Wisconsin-based outfit that was buying small, independent phone companies all over the country. In August 1973 the last call was made through the old switchboard one Saturday evening, and then Dave Chellis snipped a wire and dial service went live in Meriden.

Dick Nelson, a Valley News writer, wrote at the time that a “beloved anachronism” was lost that night.

So many stories live on about the quirky Meriden Telephone Co. and its temperamental hand crank telephones that old-timers can wax on for hours about memorable episodes, especially those when it shone as a vital community nerve center.

If there was a fire called in, Hazel Chellis could activate the village fire whistle and send firefighters from outlying areas directly to the scene. A fender-bender car accident on Main Street one evening saw Henrietta Davis, the operator on duty, direct the wrecker, relatives of the drivers and the village constable to the scene, all from her perch at the switchboard up at the Chellis farmhouse.

There was a 3-year-old boy who had watched his mom spin the hand crank to start a call, so he soon was following suit, with Hazel Chellis chatting with the kid until mother came along to end the gabfests. Operators were always helping callers track down people. Sample: “I’m sorry, Howard isn’t answering. I think he might be up at Townsends, would you like me to try up there?” Sure enough, that’s where Howard was and he would take the call. It was all in a day’s work.

A few other Upper Valley hand crank phone exchanges had hung on as late as 1960, notably Hartland’s, but Meriden was an outlier for more than a decade. Other exchanges in the area were more technically advanced but still moved calls through switchboards with live operators until these were converted to dial in the early 1960s.

Virtually all exchanges in the region had party lines, some with as many as a dozen subscribers. Getting these converted to what now is almost entirely private lines for all customers took years. Now, of course, wireless telephone systems have been supplanting many “land line” connections.

New England’s last hand crank phone exchange was in Bryant Pond, a small town near the New Hampshire border in western Maine. It reluctantly converted in 1981, but proudly is home to a 14-foot-tall statue of a classic magneto phone that ranks high among the odd tourist attractions found in the Pine Tree State.

Meriden’s old switchboard was in perfect condition when it was retired in 1973 and was hotly pursued by collectors of telephone memorabilia. Fortunately, it ended up at the New Hampshire Telephone Museum in Warner, N.H., where it can be viewed amongst a fascinating collection of old-time phone instruments and technology.

Steve Taylor lives and farms in Meriden. His phone number used to be 51-12 (one long ring, two quick shorts).

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price

Bald eagles are back, but great blue herons paid the price JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’