Vershire Salvage Yard Fined for Hazardous Waste Violations

| Published: 01-28-2017 12:23 AM |

Vershire

Sixty-four years old, with a ragged red ponytail that ends between the shoulder blades of his heavy black leather jacket, LaFlamme has owned the business along Route 113 since he bought the land 35 years ago.

He zoomed in on an image of a shiny silver truck tanker for sale, so he could read a sign saying the tanker previously held “natural, inedible” substances.

“Dog food, maybe, from a slaughterhouse,” he mused.

“This could be blood,” he said, pointing out a dark brown stain on the top of the tanker. “From the soup.”

He paused, considering whether anyone in his vast customer network might find it suitable as a storage tank for maple sap. “There’s no hazardous tag for it,” he noted.

Navigating stains and fluids, particularly hazardous fluids, is part of the job for LaFlamme, who in September was assessed a $29,000 fine by Environmental Court Judge Thomas Durkin for violating state laws governing salvage yards and hazardous waste.

The Vermont Agency of Natural Resources characterized the violations as serious, but LaFlamme and his attorney, Nate Stearns, of Norwich, say little or no harm has been done, and that they’re working to comply with an agreement with the ANR.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

Kenyon: Dartmouth alumni join union-busting effort

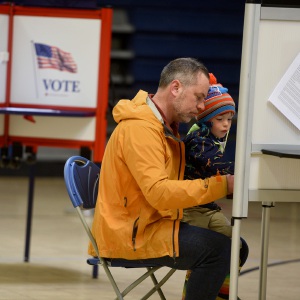

Hartford voters approve school budget and building repair bond

Hartford voters approve school budget and building repair bond

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Starbucks store planned for Route 120 at Centerra

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Local Roundup: Hanover pitcher throws a perfect game

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

Parker up for parole more than 2 decades after Dartmouth professor stabbing deaths

“I’m embarrassed,” LaFlamme said on Thursday, sitting in the office, where every flat surface has become home to a hodgepodge of items — wires, bolts, an angle grinder, a broken clock, dirty rags, a roll of cling wrap and, on the desk, three phones that look like they were manufactured in three different decades.

Outside, the general sense of disarray continues, with an estimated 800 cars on 6 acres, spilling out from behind a wooden fence and crowding Route 113. Nearly all the cars are non-operational, covered in a thin scrim of snow and waiting to be sold for parts or scrap.

Stearns said he hopes LaFlamme will be in the clear by this spring.

“The timing’s a little bit dependent on the weather, and a little bit up to the town,” he said.

In addition to the fines, the court has ordered LaFlamme to get a Certificate of Approved Location from the town of Vershire and a Certificate of Registration from the state. LaFlamme used to have the municipal certificate — they’re required for all salvage yards in the state of Vermont — but it lapsed long ago.

Vershire Selectman Marc McKee said LaFlamme has a lot to prove before the Selectboard will even consider issuing the certificate.

“He’s been in violation of his original agreement with the town for 25 years,” McKee said.

Hazardous Salvage

Vermont’s Department of Environmental Conservation estimates that roughly 42,000 cars are scrapped in the state each year, each one holding an average of between five and 10 gallons of fluids that pose a risk to the public health, including antifreeze, freon, mercury, brake fluid, battery acid, windshield washer fluid, gasoline, transmission oil, coolant and engine oil, not to mention the solvents that salvage yards like LaFlamme’s often use as they transform a wreck of a car into its constituent parts.

Trying to corral all of that fluid is a mammoth task, made more difficult for regulators by the fact that the state doesn’t even have a complete directory of the salvage yards that process them. Currently, the state counts 60 permitted salvage yards, with just two in the Upper Valley — Brown’s Sales and Service in Windsor and Hodgdon Brothers Inc. in Ascutney.

But in 2010, shortly after legislators began specifically targeting the industry for regulation, the DEC estimated that only about a quarter, or at best a third, of the total number of salvage yards operating in the state were operating with a state permit. Marc Roy, who oversees the Vermont Salvage Yard Program, was hesitant to venture a guess as to how many illegal salvage yards are in operation today.

Because many people wait to junk their cars when scrap steel prices are high, Roy said, the number of illegal yards likely fluctuates with the market, and the current low price of scrap metal likely has helped to clog Vermont’s lots with junk vehicles. LaFlamme said that, with scrap prices so low, his inventory has swollen to 800, rather than the 500 cars he said would make his yard manageable.

Violations

LaFlamme’s $29,000 fine is larger than any of the other salvage yards targeted by the ANR in 2016 — it is pursuing a $9,750 fine against B&D Service Station in Richford, $10,500 against Steve and Paul Tremblay in Highgate, $10,500 against Bettis Autoland and Salvage Yard in Hancock, and $18,000 against Willie’s Village Auto in Stowe.

LaFlamme’s fines stem largely from surprise visits from ANR inspectors who, in 2011, found nine areas of oil-stained soil. In 2013, they found two such areas, according to the court decision.

LaFlamme said the leaking of fluids was real, but minimal.

“When a car gets wrecked, the front especially, it’s going to be leaking,” he said. “That’s in every driveway everywhere. It’s not like you got a spill of a gallon, or 5 gallons. Go to any Wal-Mart parking lot and you’ll see drippage.”

The court also cited LaFlamme for burning oil-stained wood chips in a wood stove and burning off gasoline-contaminated water.

LaFlamme said he freely told the inspectors about both practices, and didn’t realize they were violations. He was in the habit of spreading small quantities of sawdust on the floor of his stripping shed, sweeping it up and burning it in his woodstove. When drums of gasoline accumulated small amounts of liquid containing too much water, he would use it to start wood fires.

“I never thought for a minute this is a big deal,” he said. “I think you have to have some common sense.”

The state also took issue with LaFlamme’s lack of documentation — when he started the business in 1982, he obtained all the necessary permits and certifications, but has since allowed his municipal permit to lapse, according to the ANR.

At his business Thursday morning, LaFlamme said that before he hired Stearns, he was an easy target for zealous inspectors.

“I’m easy to catch,” he said. “I talk too much and I didn’t have a lawyer.”

Roy, who oversees the Vermont Salvage Yard Program, said in the three years the Agency of Natural Resources has been in charge of the program, it has issued only two notices of violation for releases of hazardous materials into the environment, which would make LaFlamme an outlier.

After a round of violation notices failed to prompt LaFlamme to take corrective action, the ANR took LaFlamme to court in 2016. After a one-day trial, Durkin, the judge, issued his Sept. 1 order, in which he said LaFlamme’s violations “represent significant actual and potential impacts on public health, safety, welfare and the environment.” He also found LaFlamme had knowledge of the regulations and the violations, and failed to stop them from happening over a long period of time, with no mitigating circumstances.

The court order instructs LaFlamme to pay the fine, get both a municipal certificate and a state permit, submit a work plan for the cleaning of contaminated areas to the ANR, and stop accepting vehicles or vehicle parts onto the property.

Durkin ordered LaFlamme to come into compliance within 60 days, but his agreement with the ANR allows for a longer time frame. ANR spokesman Randy Miller said LaFlamme has made his first payment.

“He has hired an environmental consultant who has been to the site and has not identified any significant hazardous waste release,” Stearns said. He and LaFlamme said the engineer tested soil and neighboring wells without finding any cause for concern. Miller said the agency has not yet received that report.

LaFlamme has served the required public notice that he intends to file an application for certification in Vershire. Once filed, his application will be available for inspection at the Town Clerk’s Office.

McKee, the selectman, said he and others in Vershire have had complaints about the salvage yard since the ’80s.

“We wanted him to make a wall, build a fence, so when we drive down (Route) 113, we see nothing but the nice lilac bushes in front or something,” McKee said. “It hasn’t followed that in 25 years or more.”

McKee said he’s not going to pass up the chance to make LaFlamme address various town concerns about the salvage yard.

He said there are no hard guidelines that Vershire has to abide by in deciding what to demand.

“Our criteria can be anything we want now,” McKee said. “We could tell him he has to jump over the moon.”

Vehicle Organization

To understand the root cause of LaFlamme’s violations, one only has to watch him sitting in his office, among the piles of tools and car parts, and listen to him talk about falling in love with Henrita, a woman who he met online 10 years ago and who lived in Mindanao, an island in the Philippines.

The two decided to get married, and LaFlamme agreed to travel to Mindanao that August. But he had a problem with the paperwork.

“I couldn’t seem to get my passport together,” he said, adding, in some of the same type of language he used to describe paperwork mishaps related to his efforts to get permitted: “I don’t know what the trouble was.”

The day before he was scheduled to fly out of Boston, LaFlamme drove to the National Passport Center in Portsmouth, N.H., where he wrangled a last-minute passport. In Boston, he learned he had misread his ticket, and arrived too late to board his flight. He wound up taking a later flight that routed him through Chicago, and got to his wedding on time — barely.

That’s LaFlamme.

“I’m not organized at all,” he said. “I don’t dot my I’s, and I don’t cross my T’s.”

The most complete record of LaFlamme’s inventory is kept between his ears. His entire bookkeeping system consists of a $3 composition book that he keeps next to his computer monitor.

When LaFlamme got the violation notices from the state, he said he contacted both the town and an engineering firm with good intentions of bringing his business into compliance. But at some point, both of those processes got derailed, and he didn’t shepherd them through to completion.

“Sometimes in business, other things take priority,” LaFlamme said. “Did I ignore them to some degree? Probably I did.”

And even now, with both the state and the town threatening to close down his business, he was acutely aware of the need to continue to earn money, both to pay the fine (combined with his attorney fees, which he expects to be $40,000 out of pocket), and to allow him to plan his next trip to the Philippines, where he now has three young children with Henrita.

He looked at another listing on the computer screen, a Terex crane he was thinking of buying. New, it would bring $170,000. This one was on sale for $7,000.

“I don’t have any use for it,” he said. “But I’m going to find somebody that does.”

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling can be reached at mhonghet@vnews.com or 603-727-3211.

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex

Football helmet maker buys Lebanon’s Simbex