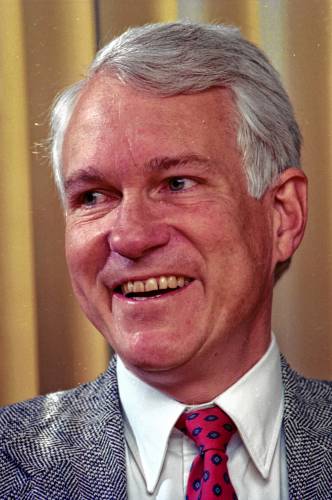

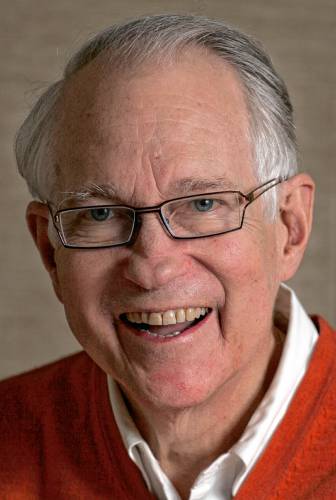

Former Valley News publisher challenged newsroom to seek continuous improvement

| Published: 03-15-2024 10:01 PM |

John Kuhns arrived at the Valley News at a big moment for the small, busy newspaper.

His predecessor as publisher, Willmott “Bin” Lewis, announced in January 1993 that he would step down that spring with Kuhns to replace him. Just before Kuhns started, the paper made a long-planned move to morning publication. And a few months after that, with Kuhns at the helm, the Valley News introduced a Sunday edition.

What these changes, and Kuhns’ arrival, ushered in was a kind of golden age for the Upper Valley’s largest newsgathering operation. Morning publication and the Sunday edition made the paper more attractive to advertisers, ad revenue went up and the paper plowed the money back into the newsroom. With more than 30 reporters and editors, the Valley News had one of the largest newsrooms for a paper of its circulation in the country.

“I would say it’s a wise leader who recognizes there are good foundation stones in place and builds on them,” Jim Fox, Valley News editor from 1989 to 2006, said of Kuhns.

Not only did Kuhns build on those foundation stones, he later declined to undermine them. When newspapers started giving their reporting away for free on the internet, Kuhns decided against it.

“He was very firm in his conviction on that,” his wife, Janet Milne, said in an interview. “Why give away for free what you’re investing a lot of money in producing?”

Kuhns died Feb. 20, in Boston, of complications from the flu. He was 77.

Though he took a winding path to the Valley News, Kuhns had always wanted to be a newspaper publisher.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

He was editorial page editor of the paper at Central High School in Omaha, Nebraska, where he grew up. His father was a lawyer with an expansive practice that included representing the Omaha World-Herald.

At Stanford University, Kuhns majored in history, and even considered getting a doctorate and becoming a professor, Milne said. The potential challenge of finding work in academia pushed him away, and the prospect of having an influence in public life pulled at him. He went to Yale Law School, then, as now, a kind of finishing school for the corridors of American political power. Kuhns blazed his own trail, though his father’s practice was a model in one respect.

“My sense is that what John admired about his legal work was how it allowed his father to be a force in the community,” Milne said.

While at Yale, Kuhns took a Saturday seminar taught by Edward Bennett Williams, co-founder of the Washington D.C. law firm Williams & Connolly.

In 1970, Kuhns published an article in the Yale Law Journal — the journal quaintly calls them “Notes” — titled “Reporters and Their Sources: The Constitutional Right to a Confidential Relationship.” By the time he graduated, in 1972, Daniel Ellsberg had leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, and Williams & Connolly had taken on the Washington Post as a client. Yale Law School grads generally have their pick of jobs, and at least one of his professors, Milne said, urged Kuhns not to go work for Williams, then just a small, 5-year-old firm.

“He was just willing to go do what he thought was right for him,” Milne said.

He was the 16th lawyer to join Williams & Connolly, and he stepped right into the Post’s coverage of the June 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate Complex.

While working for the Post and other media clients, Kuhns advised them about libel law and about testifying in court without revealing their confidential sources. Advising a newspaper consists more in helping it get vital, often hard-won information into print, than in urging caution, and though Kuhns projected Midwestern calm he was as hard-charging as the reporters and editors he worked with.

“He always loved the reporters and loved representing reporters in libel cases,” the Post’s celebrated Executive Editor Benjamin Bradlee told the Valley News in 1993. “His goal was always getting the story into the paper. Reporters loved that.”

Kuhns was made partner at Williams & Connolly in 1977, and the Post hired him away in 1982, first as director of business planning. In that role, he oversaw the launch of the Post’s National Weekly edition in November 1983. He had developed a strong working relationship with Bradlee and with Managing Editor Howard Simons and it did not take much convincing to lure him into a job in the newsroom. As deputy managing editor for administration, he was the first non-journalist to work in the Post’s newsroom.

“At that point, the Post newsroom staff was around 550 people,” Milne said, with a budget of around $40 million.

Even so, Kuhns viewed his work at the Post as another step on the road to becoming a publisher. “I was very broadly exposed to the news side of the business,” he said in 1993.

At one point, the Post was considering buying smaller regional papers, and Kuhns would have been in line to serve as a publisher. But at a time when newspapers were doing quite well, acquisition costs were too high, and the Post abandoned that plan, Milne said.

Along the way, Kuhns had met George Wilson, then the president of Newspapers of New England, through the American Newspaper Publishers Association. Though Kuhns left the Post in 1988 and went to work in finance, he became a member of the NNE board of directors in 1990. When Bin Lewis was ready to step down, Kuhns, then only 46, was ready to step in.

He started just a week after one of the most momentous changes in the paper’s history, the shift from afternoon to morning publication. While the change was intended to help readers and advertisers, it transformed how the paper’s employees went about their work.

An afternoon paper makes decisions about what it’s going to publish early in the morning with a deadline around midday. As a morning paper, the Valley News reporters and editors worked through the day until a 4 p.m. news meeting, when daytime staff handed the reins to the night copy desk. The deadline for pages was midnight, but could go later for special events. The press, acquired under Lewis and capable of turning out 45,000 copies an hour, would complete its run by 2 a.m. or so. Editors and pressmen accustomed to being home for dinner had to get used to leaving the office in the wee hours.

The change “turned people’s work lives and personal lives upside-down,” Fox, who started at the paper in 1988 and became editor in 1989, said in an interview.

Though he had a big job on his plate — launching the Sunday paper — Kuhns started work at 24 Interchange Drive in West Lebanon without much fanfare, in deference to the people who, a week before had started working at night.

“What was really notable to me was that he didn’t come in and bring everybody together and pronounce a grand plan or a mission statement,” Fox said. He let the newspaper keep up its work and set a goal that sounds modest, but isn’t: ” ‘I just want to get better, every day, every week, every year,’ ” he told Fox. “It’s really quite an ambitious goal to get better at what you do all the time.”

In his July 31, 1993 announcement of the planned September launch of the Sunday Valley News, Kuhns wrote: “Our news department is hiring four or five new reporters and editors, which will increase its size by about 20 percent.” The paper also added two new people in production and other part-time staff.

In preparation for the launch, the newsroom mocked up an entire Sunday paper, and the process didn’t go as well as Fox had hoped. “I said, ‘I’d like to do this again before we launch it,’ ” Fox said. Kuhns gave the OK, which meant an additional outlay of overtime, paper and ink. When the first issue launched, “it came off without a hitch,” Fox said.

“He just projected a sense of stability, which I think we needed right then,” Fox added. “He conveyed early on that he wanted us to be aggressive in our reporting.” And he encouraged the newsroom to extend its oversight beyond government to other big institutions, including major nonprofits.

At the same time, Kuhns was attentive to the business community in the Upper Valley. He was a longtime member of the Hanover Rotary, which kept him in touch with business leaders. Though he had an open door, Kuhns didn’t go out of his way to schmooze with people in power, Rich Wallace, the paper’s longtime advertising director, said.

“I think he looked at it as what we did and what we reported spoke for itself,” Wallace said.

By the turn of the century, the newsroom had grown further. It comprised a mix of veteran editors and reporters and promising young ones, some right out of school. Among the veterans was Jim Kenyon, who came back to the Upper Valley in the mid-1990s after a stint as a reporter at the Tampa Tribune and was covering Montpelier.

The larger newsroom and the influx of veteran talent enabled the paper to produce what many consider one of its finest moments. Fox assigned Kenyon to write a series of stories about working people who struggled to keep a foothold on the necessities in the Upper Valley.

“John was very supportive of it all,” Kenyon said. “It wouldn’t have happened without him. He was very engaged in what the newsroom was doing.”

The paper was able to hire Jeff Good, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the St. Petersburg Times, to cover Montpelier while Kenyon took a year to report The Other Side of the Valley, an in-depth look at four families living on the economic margins in an area that prides itself on its sense of community.

“That really shook things up in the Upper Valley, in the complacent circles of the Upper Valley,” Fox said. Published in late June 2001, the series might have shaken things up even more had the news not turned on Sept. 11 toward terrorism and the nation’s response to it.

Building up the paper’s economic might made this work possible. Newspapers operated as a kind of virtuous circle, with better funding producing a better news product, which brought more readers to the paper. “What that gave us was the gift of time,” Fox said. More funding meant more hours of bringing information to light in words and images, and more hours to edit it into attractive pages and graceful stories.

After building this up, Kuhns was loath to give it away, which is what newspapers started to do once use of the internet started to become more widespread, in the 2000s.

“Newspapers are like every other business,” Fox said. “Whatever is trendy, people get on board with, and he just said, ‘No.’ ”

What this meant was that as other newspapers suffered double-digit losses in subscriptions and advertising dollars over multiple years, the Valley News lost far less, and in some cases made gains when the entire industry was declining.

“To this day I bring it up to people,” Valley News publisher Dan McClory said in an interview. “It’s one of the things that set us up to be successful.”

The internet’s disruption hasn’t spared the Valley News. It stopped printing in West Lebanon in 2019 and sold its press for scrap, and it sold its building in 2022. After retiring as publisher in 2008, Kuhns became chairman of the Newspapers of New England board, where he helped guide the paper through the end of the golden era he’d overseen.

But newspapers that put all their work online for free are in far worse shape. (Indeed, about a quarter of American newspapers have closed in the past 20 years, and the survivors are shadows of their former broadsheet selves.)

“They’re still charging very little for digital subscriptions because they started at zero,” McClory said.

Kuhns’ legacy at the paper lives on in the people he hired and nurtured, another of his strengths. He brought McClory to West Lebanon from the corporate office in Concord, and he encouraged Wallace to grow into the ad director’s job, which he assumed in 1994, at the age of 29.

“I wouldn’t be sitting here today if it wasn’t for him,” McClory said.

The latter half of Kuhns’ time as publisher was disrupted by a pair of kidney transplants, the first in 2000, the second in 2006. Each time he took about six weeks off, then got back to work, Milne said. It was a hereditary condition that afflicted him earlier than expected.

“He kind of did his utmost to make sure his health didn’t get in the way,” she said. When necessary, he’d leave his home in Etna by 4 a.m., drive to Boston for tests at 6 a.m. and be at his desk in West Lebanon by 9. “He was just determined that he was going to do his job.”

Alex Hanson can be reached at ahanson@vnews.com or 603-727-3207.

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’

A Life: Richard Fabrizio ‘was not getting rich but was doing something that made him happy’