Out & About: In honor of Day of Remembrance, woman shares late husband’s story of internment

|

Published: 02-23-2024 9:46 PM

Modified: 02-26-2024 3:47 PM |

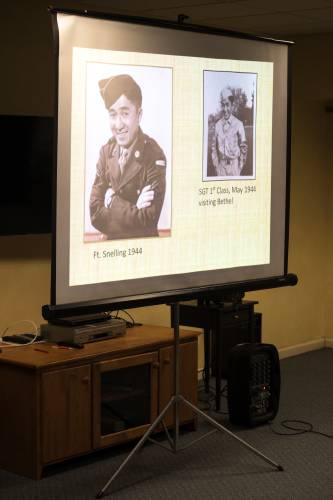

LEBANON — Dorothy Whitney Yamashita pointed to black-and-white photographs of her late husband, Kanshi Stanley Yamashita, on screen.

There he was, as a child on Terminal Island off the coast of California. There he was with his siblings. Their idyllic childhood would come to an end on Feb. 19, 1942, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced interment of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast as the United States fought Japan during World War II.

But Dorothy Yamashita — who turns 99 in April — wasn’t there at Harvest Hill in Lebanon on Tuesday to talk about American history. “All of you know what happened historically,” she told the roughly 50 people gathered in a room at the assisted living facility on the Alice Peck Day Memorial Hospital campus in Lebanon, one day and 82 years after that executive order was signed. “I am going to share more of our family history.”

Her talk was inspired by the Day of Remembrance, which Japanese Americans recognize on Feb. 19 to mark the signing of the executive order.

Shortly after the executive order was signed, FBI agents came to arrest Kanshi Stanley Yamashita’s father, Kiyoo, who owned a fishing boat. They “wouldn’t even wait for his wife to pack a suitcase,” Dorothy Yamashita said.

Kanshi Stanley Yamashita’s sister, Iku, rushed out the door to slip a bible through the window of the vehicle that was taking her father away. “That was always a vivid memory for her,” she noted.

Dorothy Yamashita, who grew up in Tunbridge, emphasized that her husband’s family’s experience was not unique.

“This is what was happening everywhere,” she said. “War hysteria.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

While the U.S. Navy said that all people of Japanese descent would be removed from Terminal Island on March 14, Lt. General John L. DeWitt decided “that these Japanese aliens were very dangerous,” Dorothy Yamashita said, using a phrase that was common at the time.

On Feb. 24, DeWitt moved up the deadline to Feb. 27. Families could only take what they could carry. The Yamashita family was taken in by a Baptist church in Los Angeles — not the horse stalls others were subjected to — while they waited to see where they would be sent.

“They were lucky,” Dorothy Yamashita said.

In the meantime, the U.S. government worked to find a way to house tens of thousands of people. They built “10 huge, I’m going to call them concentration camps,” she said, noting that while Japanese Americans did not suffer the horrors of the Holocaust, “it was still a humiliating experience.”

The Yamashitas ended up at Poston, an internment camp in Arizona. Kanshi Stanley Yamashita spent less than a year there before a Baptist group helped him gain admission to Bethel College in Minnesota. After around a year, he decided to join the Army. He was stationed in the South Pacific, where his assignment was to be a translator at a prisoner of war camp.

The government released people from the internment camps in August 1945, after two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, signaling the end of WWII. They were given $25 to go home, Dorothy Yamashita said.

“Well they had no home,” she said. “Very few had a home to go to.”

After his military service, Kanshi Stanley Yamashita went to Antioch College in Ohio, where he met Dorothy, and the couple was married in 1950. He was called up to serve in the Korean War and eventually spent more than 30 years in the Army, primarily in military intelligence.

Kanshi Stanley Yamashita’s parents returned to California, where they spent 17 years working as domestic servants. When their son’s family visited, they left through the servants entrance. One time, one of their three daughters said she wondered how it felt to be a servant. Dorothy Yamashita said they had never considered that.

“My husband and I were just happy they had employment in such a comfortable environment,” she said. “The repercussions of that order” carried over. Her father-in-law would never again own a fishing boat.

For the most part, Kanshi Stanley Yamashita kept his experiences at the internment camp to himself — his daughter, Dana Yamashita, who was visiting from Troy, N.Y., to attend her mother’s talk, recalled afterward that she didn’t even know about his time there until she was working on a report about Japanese internment camps in high school. But following his retirement from the military in 1978, he decided to pursue a doctorate in comparative culture from the University of California. His dissertation was about Terminal Island.

It was around two years after President Gerald Ford signed Proclamation 441, on Feb. 19, 1976, which officially terminated Roosevelt’s executive order that forced Japanese Americans into camps. That helped set off a period of advocacy which eventually culminated in 1988 when Congress passed reparations for Japanese Americans who were imprisoned and their families.

Some people were reluctant to revisit the past, “but the second generation said, ‘For the sake of your children, we need you to tell what you lost,’ ” Dorothy Yamashita said. “I was able to attend some of those hearings. They were heartbreaking.”

After the couple moved to the Upper Valley in 1996, Kanshi Stanley Yamashita began sharing his story with area high schools and organizations. After his death in 2005, Dorothy Yamashita started doing the same. It was important, she said, to study all parts of U.S. history — the good and the bad. That includes recognizing the generational impact.

Dorothy Yamashita concluded her presentation by reading from a piece her grandson wrote about the internment camps when he was 14. He is now a teacher.

“I think teachers help to break the unbreakable cage of ignorance,” she said. “The other key is forgiveness.”

Dorothy Yamashita then asked the group to join her in singing one of her favorite hymns, “Open My Eyes That I May See,” which begins: “Open my eyes, that I may see/ Glimpses of truth thou has for me;/ Place in my hands the wonderful key/ That shall unclasp and set me free.”

Liz Sauchelli can be reached at esauchelli@vnews.com or 603-727-3221.

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm  JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’