Woodstock Country School Shined Brightly, Briefly

| Published: 07-03-2017 10:00 PM |

E

“Every time I drive into downtown Woodstock, I drive by Greenhithe,” Boardman, a 1956 graduate of the progressive boarding school, said last week of the school’s original home, a former inn, on Church Hill. “I never don’t think about it.”

The one year that Spittle attended the school, in the mid-1970s, made its mark on the then-16-year-old. And she wasn’t alone.

“It’s uncountable; lots and lots of people in this area have connections,” Spittle said last week from the school’s former library, now the tack shop that she owns next door to the Green Mountain Horse Association headquarters. “You don’t necessarily know it until it comes time to have a reunion.”

While surviving graduates and faculty remember the peculiarities of Woodstock Country School, which existed from 1945 to 1980, Boardman suspects that to most people outside that circle, “it’s pretty much a secret.”

That’s part of why Boardman, a former Windsor County assistant judge and an off-and-on journalist, spent more than 35 years — just about as long as the school had existed — assembling the 500-plus-page Woodstock Country School: A History of Institutional Denial.

He wrote the first couple of drafts from 1982 to 1987, only to see the Woodstock Country School Foundation, which was dissolved in 1990, deny further support for the project by moving most of the archival material that Boardman had been using to the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Boardman retained some written material, and with more interviews of surviving faculty, alumni and trustees he continued chipping away at the book, which Yorkland Publishing in Ontario, Canada, printed in 2016. It chronicles the school’s turbulent history with a mix of archival and candid photographs, student artwork, interviews with alumni, former teachers and trustees and documents ranging from minutes of meetings of the faculty and headmasters’ letters to the trustees to letters between alumni and student council newsletters.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

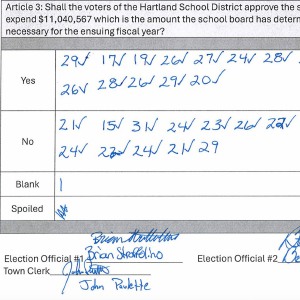

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

With support from several well-to-do Woodstock residents, Ken Webb founded the school in 1945, with the aim of establishing, according to his 1944 prospectus, “a coeducational progressive farm and day school” that would “strive to stimulate in manifold ways intellectual curiosity, mental alertness and pride in sound scholarship.” At the urging of supporter Elizabeth Forrest Johnson, former headmistress of the Baldwin School for Girls in Bryn Mawr, Pa., Webb agreed to hire David Bailey, a teacher and housemaster at the private Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, as headmaster.

Despite differing philosophies — not least Webb’s abhorrence of cigarette smoking and Bailey’s love of nicotine and use of smoking privileges to reward students — they forged a partnership that attracted students who often struggled in other educational settings. Among those who spent at least a year at the school were future Dallas and I Dream of Jeannie star Larry Hagman, the three children of folk singer Pete Seeger — who performed several times at the school — and writer Susan Cheever, daughter of author John Cheever. With some bumps in the road, the school managed to thrive, until Bailey developed emphysema.

Everybody connected with the school knew the basic story, Boardman said. “David Bailey got sick, couldn’t really cope. The trustees twice hired headmasters who were wildly inappropriate for the school.

“The kind of school it was, when it was working well, could have survived, and could have worked now.”

It worked well enough for Boardman, who’d boarded unhappily at the Harvey School in Katonah, N.Y. In the book’s introduction he recalls entering the school in 1952 “as an immature, socially unprepared, intimidated and withdrawn 10th grader.

“Slowly Woodstock would become the first place in more than seven years where I felt safe, the first place I knew where I wasn’t beaten up, the first place where I didn’t have to live in constant fear and wariness. After so many years of grown-ups lying to me, at WCS I would find some who sometimes told the truth — that was stunning and liberating.”

Midway through his years at Woodstock, Boardman watched while the Church Hill classroom building, a former barn, burned to the ground. He also had a front-row seat for the ensuing move to South Woodstock, where the school occupied the part of the former Owen Moon horse farm that now belongs to the Green Mountain Horse Association.

Upon his return to the school to teach drama in 1971, Boardman notes in the book, he found it in the middle of the revolutions in sexual mores and recreational drug use that the rest of the culture also was wrestling with. On top of those changes, Boardman writes that “the faculty was bitterly divided and utterly selfish. The Trustees were feckless and remarkably obtuse. The student Trustees and other students tried without success to get the grown-ups to understand how they were destroying the school.”

By the mid-1970s, the school was struggling financially, and went through a series of headmasters. In 1980, it graduated its last senior class.

“David Bailey once said if he were to write a book about WCS, he would call it Felicity Awhile, a reference to Hamlet, Act V, scene ii,” Boardman writes, before closing the narrative with this excerpt:

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity a while,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

To tell my story.

Boardman estimates that he’s given copies of the book to about 100 alumni and former staff. And last he knew, one copy was available at the Yankee Bookshop in Woodstock. He hopes that readers, involved and otherwise, appreciate the story’s relevance to the tumult that education and the wider society are now undergoing.

“In a way, our culture is in a similar place now that it was in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” Boardman said. “You’ve got de-personalizing forces — this time things like social media and the internet. At its best, the school was more integrating for kids. Now the country’s going through so much of the same kind of metamorphosis. We have a country that’s immersed in institutional denial.”

For all of the school’s faults, which prompted Boardman to move on to other pursuits in 1976, a 16-year-old Laura Spittle arrived in 1975 to find a welcoming environment, just up the road from her grandparents’ farm, where she’d spent many childhood summers.

“It had a reputation for being ‘progressive,’ was the term that was used at the time,” Spittle said. “What that really meant was teaching kids to be responsible for themselves. … It demanded of all of us that we behave in a way that benefited the entire community. … Teaching kids to be part of a community was what the Country School’s takeaway was. It was an experiment. Experiments have results, and results are what we learn from.”

While she only spent a year on the South Woodstock campus, Spittle never really left, except for her years at Emerson College. Six years after the school closed in 1980, Spittle and her mother bought 11.3 acres at the corner of Route 106 and Morgan Hill Road. And more than two decades after she sold the property’s barn and duplex house to the Green Mountain Horse Association, Spittle continues to run her Vermont Horse Country Store out of the school’s former library next door to GMHA.

Every five years, she also co-organizes reunions of former students, teachers and staff, housing many of them in the former campus farmhouse that she also still owns.

“I just got an email today from a former teacher,” Spittle said on Friday. “He said something like, ‘Reunion: I’m wondering if we can stay in Doubleday Farmhouse?’”

The official reunions, she added, continue to attract as many 250 of the estimated 2,000 individuals with direct connection to the school.

“People come out of the woodwork,” said Spittle, who also manages the Facebook page You Know You’re from the Woodstock Country School When … ? “These people are very invested in each other. In the world we have now, a lot of people are thirsting for community. These people value what they got here.

“They value this place.”

David Corriveau can be reached at dcorriveau@vnews.com and at 603-727-3304.

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm