Ex-Officer Shares Experience as Transgender Woman

| Published: 11-21-2016 11:27 PM |

Norwich

Alden gave the keynote talk on the annual Transgender Day of Remembrance and Resilience, a national event that commemorates transgender people who lost their lives to violence in the past year.

Alden, a 1991 Dartmouth College graduate, left the Lebanon police force this year after more than two decades’ service. In an hour-long address to an audience of about 30 in the meeting room of the Norwich church, she chronicled transgender people’s efforts to carve out a place in society, and the progress that has yet to be achieved.

“We adapt long enough to survive, and then we set about making our surroundings survivable,” she said.

Alden also fought back against criticisms that advocates’ insistence on terminology constituted a stifling form of “political correctness.”

For transgender people, words can affirm life, and they can threaten death, she said.

“When a waiter misgenders us, for many of us it starts a neural cascade of environmental threat assessment,” she said. They look around to see whether anyone noticed, she said, and then assess bystanders’ faces “to decide if any of them look angry or upset enough to direct it at us.”

“We sit down with our backs to the wall, with a clear line to the door, and then we try to eat,” she said.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

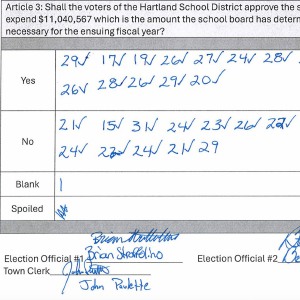

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

The danger is not a fiction, Alden said. Transgender people are victims of hate violence at a higher rate per capita than any other demographic group in the United States.

Advocates tracked 21 deaths of transgender people from hate violence in 2015; this year, with a month to go, has already matched that number.

They also have a higher risk for self-harm. Compared to 4.6 percent of the general population, about 41 percent of transgender people report having attempted suicide, according to a 2014 survey from the UCLA School of Law and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Transgender people face a daily barrage of invalidation that manifests itself every time a person declines to acknowledge and respect their expressed gender identity, Alden said. It happens everywhere, whether at work, in church or in line at the grocery store.

“Each misgendering is a bee sting,” she said, “and if you get enough of those it can stop your heart.”

She also spoke of her own transition, in late 2012, and how her colleagues at the Lebanon Police Department handled it.

“When my transition was announced, my co-workers had never seen me as myself and heard my voice as you are hearing me now,” she said. “They envisioned disaster because they pictured a man in drag trying to do law enforcement and the negative public reaction.”

By early 2013 Alden, who is now 47, was out doing police work while, as she put it, “presenting as a woman.”

Her fellow officers were “shocked,” she said, to discover that “once I styled my hair and wore makeup and used this voice, the public generally saw me as a woman.”

But it took her a long time to get there, she said. For some time after realizing that she was a woman, she hid it from her colleagues, her friends and even from family members, she said, “in the hope that someday I could transition without losing them.”

Now, with Donald Trump as the president-elect, many of the protections that transgender people gained in recent years could be lost, including gains by executive orders from President Obama, which are easily reversed.

New Hampshire, for example, used to require proof of gender reassignment surgery before allowing people to change the gender marked on their driver’s licenses. So for years, Alden said in an interview after her talk, she served as a police officer while presenting as a woman, yet was forced to carry a driver’s license saying she was male.

Although the state’s law was recently eased, and is not directly dependent on the actions of the federal government, the Trump administration could reverse that kind of progress nationwide, Alden said.

“Could the federal government set the tone?” she asked. “Sure.”

The coming years also could see more laws like North Carolina’s H.B. 2, the controversial statute that bans people from using bathrooms that don’t correspond to the gender designated to them at birth.

Not only could Trump set off anti-transgender action in government, Alden noted, there are fears his rhetoric also could incite violence.

“It’s a scary situation all around,” she said.

This coming summer, the U.S. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear the case of Gavin Grimm, a transgender man denied use of the men’s bathroom in his Virginia high school.

Since the death of Antonin Scalia, the court has lacked a ninth justice, and Trump will have the opportunity to appoint one — and maybe others.

“Whom our president-elect appoints to that could have a very chilling effect and establish a very bad legal precedent for trans people for a long time,” Alden said.

Amid the mounting concern that the coming years will bring setbacks for already marginalized people, it is even more important that wider society make an effort to understand its least powerful members, Alden said during her talk.

“This is why LGBT people invent words and concepts,” she said. “We’re not trying to be difficult; we’re trying to be accurate.”

For instance, Alden said, some people may think of a transgender person as having chosen to switch genders. But for her, the opposite is true: Regardless of the gender assigned her at birth, she was always a woman, and now openly acknowledges it.

Alden’s transition, she said, was therefore less a change than a revelation.

“Their experience is I was a man, and then I was a woman,” she said. “My experience is I had to hide myself so thoroughly that even I forgot I was in disguise.”

To understand and support transgender people, Alden said, the popular consciousness is in need of a major shift — one she likened to the discoveries of Copernicus.

Just as the Polish astronomer upended the prevailing models of the universe, where the celestial bodies supposedly revolved around the Earth in a set of crystal spheres, people conscious of non-binary gender identity must overturn the notion that people are locked into one of two genders assigned them at birth, Alden said.

“Go ahead and insist on language with the people you encounter,” she told the crowd.

Although some people will dismiss the distinctions, she said, others will embrace them, and those are the allies transgender people must seek out.

Alden recalled that her wife, Sparrow, offered her that kind of support. Once, Alden remembered, Sparrow was asked why using the correct terminology for transgender people was so important.

“Someone I love has asked me to do this for them,” Sparrow Alden said. “Therefore, I do it.”

Later on Sunday evening, people gathered in the church meeting room to light candles and read the names of transgender people who lost their lives.

Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, the 19th-century labor organizer who helped to found Industrial Workers of the World, had a saying that Alden believed would help those present on Sunday to mourn, and then take action.

“Pray for the dead,” Alden said earler that day, quoting Jones, “and fight like hell for the living.”

Rob Wolfe can be reached at rwolfe@vnews.com or at 603-727-3242.

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination