Dartmouth College Aims to Boost Faculty Compensation

| Published: 10-31-2016 12:30 PM |

Hanover

The move to compete on pay comes after faculty salaries and benefits at Dartmouth fell behind the rest of the Ivy League during the Great Recession. Dartmouth has not yet closed that gap, and its tenure-track faculty’s average compensation is now closer to that of top public universities than what is offered at its Ivy rivals.

In 2015, the average tenure-track faculty member — that is to say, an assistant, associate or full professor engaging in the career-long tenure process — made about $177,000 in salary and benefits at Dartmouth, or roughly $15,000 less than the average Ivy League counterpart, according to data compiled by the American Association of University Professors.

Faculty members in recent years have been lobbying for better pay, arguing that it allows Dartmouth to attract and hold on to the best scholars, which in turn affects student education and the overall quality of the school, they say.

“With a focused dedication to academic excellence, Dartmouth is committed to recruiting and retaining faculty who are internationally preeminent as scholars and teachers in their disciplines,” the trustees said in a September news release. “In order to provide the intellectual and pedagogical environment in which Dartmouth faculty can optimally thrive and contribute to their fields as well as to the Dartmouth community, compensation must be competitive in relations to select peer institutions.”

Dartmouth Report on Faculty Salaries 14-15 by Valley News on Scribd

The trustees directed administrators to find “benchmarks” to measure up to, but did not set a deadline for the compensation shift, nor suggest how much of an increase to make.

Michael Mastanduno, dean of the faculty, said in an interview earlier this month that professors, themselves, had been the impetus for this announcement. In the spring of 2015, the arts and sciences faculty voted to ask trustees to review compensation and consider an increase.

As dean, Mastanduno is an ex officio member of the Committee on Faculty, a group that speaks for faculty members on financial concerns, among other matters.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

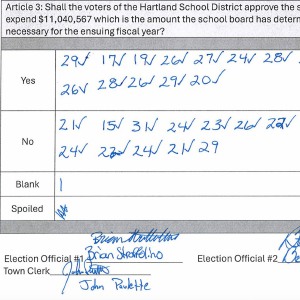

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Around the same time as the faculty vote, Eric Zitzewitz, an economics professor and former committee member, released a study that described how and to what extent Dartmouth had fallen behind.

In recent years, Dartmouth has compared its compensation scale for adjuncts and tenure-track faculty with a group of 35 schools called the Consortium on Financing Higher Education, or COFHE, which includes the eight Ivies, many of U.S. News & World Report’s top 20 schools, and several top liberal arts colleges.

Using publicly available statistics from the American Association of University Professors, Zitzewitz composed graphs showing how Dartmouth’s compensation tracked the COFHE group for the years leading up to the financial crisis, at which point the college’s pay scale stalled and then fell behind.

In the past academic year, according to publicly compiled statistics, a full professor at Dartmouth, the highest level of faculty standing, made on average $233,500 in salary and benefits. There were 390 full professors across all of Dartmouth’s academic programs, according to figures from the school’s Office of Institutional Research.

Although the number is high compared with many other Upper Valley salaries, it trails those at peer schools. A full professor at Harvard makes $278,000; at the University of Pennsylvania, $260,000; and at Yale, $245,000, according to AAUP statistics.

Zitzewitz last year helped make the case for a compensation increase, noting that a relatively small difference in pay makes for a big difference in quality — at least when comparing the academic reputations of schools.

Increasing the average full professor’s compensation at Dartmouth by 5 percent would place it just behind Yale, he calculated, and cutting it by the same amount would bring Dartmouth down below the pay rate of Boston University.

In interviews this month, Zitzewitz and other academics drew a connection between faculty compensation and the educational standing of a school.

In a “reasonably competitive” market like academia, Zitzewitz said, attracting and keeping the best faculty is substantially more difficult for Dartmouth if its pay isn’t comparable to that of its peers.

“Nobody’s going to say, ‘I left because my raise was $1,000 too low to retain me,’ ” but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, he said.

The result of this disparity, he said, is that “we fail to attract the people we’re trying to hire, and we fail to retain the people we’re trying to retain.”

Zitzewitz added, however, that his study had not looked into retention and hiring success, nor had it investigated distribution of pay across fields of study and individual faculty members.

The cost of living, which also could affect compensation offerings, did not factor into Zitzewitz’s study, either.

Comparing the Upper Valley to the surroundings of other schools — those located in cities, for instance — is “trickier than it seems,” he said, given that the government does not publish statistics that compare price levels across geographic regions.

Psychology and brain sciences professor Todd Heatherton, who has served on the Committee on Faculty intermittently since the 1990s, said Dartmouth’s peculiarities — its rural setting, the need for people who are both scholars and teachers — made it a bit harder to find the right hire.

“At Dartmouth we pursue people who are hard to come by,” Heatherton said. “We want them to be excellent scholars and superb teachers. That’s a difficult talent set to get.”

Heatherton and others said Dartmouth faculty members are closer to students — not only through teaching but also through their research, in which they frequently involve undergraduates.

Heatherton also noted that faculty compensation plays into another indicator of academic standing, albeit a controversial one: rankings. The U.S. News & World Report rankings of research universities, perhaps the most influential measure, directly compares how schools compensate their teachers.

Heatherton said the trustees’ compensation statement in September had followed years of promises from administrators.

In the late 1990s, faculty, administrators and trustees were “concerned that Dartmouth was falling behind,” Heatherton said, which spurred administrators to announce a “migration” toward the median of peer schools’ pay.

“That was a pretty good goal,” Heatherton said, “and over the next decade we managed to achieve it.”

Compensation caught up through the early 2000s, he said, until 2010, when the worldwide financial disaster handed Dartmouth its own budget crisis. A salary freeze took effect and, after a year of no raises and another year of “soft freeze,” as Heatherton called it, Dartmouth discovered that other schools had not tamped down as hard on faculty pay.

“We lost considerable progress compared to how we’d been,” he said.

Meanwhile, as compensation lags peer schools, professors seek outside offers — either to provide leverage for a raise, or actually to leave.

Faculty members at Dartmouth feel they “have to make a case by getting an outside offer,” Heatherton said, and since the school fell behind, this practice has become more frequent.

“I think this is what the trustees and President (Phil) Hanlon were reacting to recently,” he said.

All the same, he said, the school has been proactive in identifying its “most poachable” faculty members and keeping them happy. Rumors fly about offers for the most eminent scholars, Heatherton said, forcing deans to act.

The dean’s office reviews faculty members’ pay for merit increases, but faculty pay is also part of the budget process, which involves the whole college.

For Mastanduno, the dean of the faculty, heading off poaching attempts is part of the job.

“You have a whole set of early warning systems that help you understand someone’s situation,” he said, so it’s “fairly rare,” in his experience, that problems with a restless faculty member come out of the blue.

“We don’t expect we’re going to win every one, but we certainly don’t want to be on the defensive,” he said.

For example, Mark McPeek, a veteran biology researcher and teacher who holds an endowed professorship, said he had received a handful of unsolicited offers in his more than 20 years at Dartmouth, along with many more invitations to apply to outside jobs. This is not uncommon to faculty, he said, and like many others, he rejected them all.

“Others might see this as a problem, but I don’t,” McPeek said in an email. “Many of my colleagues across the entire institution of Dartmouth are among the best people in their respective fields, and so of course other institutions are trying to lure them away. ...

“People only hear about those who actually leave, and not about all the people who stay.”

Dartmouth College, according to internally compiled statistics, employs 607 arts and sciences faculty members, both tenure-track and adjunct, and 459 more in the professional schools.

Many more college employees — about 3,500 — are not faculty. And as the college’s academics contemplate a bump to a higher pay scale, some of those staffers say they feel comparatively undervalued.

One white-collar Dartmouth administrator, who asked for anonymity to speak about the situation involving an employer and salaries, said the “culture of power” is reversed between faculty and staff.

“The cultural sense for faculty is that Dartmouth is lucky to have them,” the administrator said. “The cultural sense for staff is that we are lucky to have Dartmouth.”

Because staffers are considered more easily replaceable, Dartmouth sees less need to compensate them at competitive rates, the administrator said.

And at the same time that faculty members were suffering through recession-based wage freezes, many staffers were fighting for their jobs.

In 2009, former President Jim Yong Kim’s administration laid off a small number of union employees and, although some later were re-hired, students banded with the union to protest further cuts to benefits in a campaign called “Students Stand With Staff.”

Chris Peck, president of Local 560 of the Service Employees International Union, the labor union that represents some 500 painters, security officers, food-service employees and other blue-collar Dartmouth workers, said his colleagues were struggling to meet costs despite having negotiated raises.

The latest contract cycle, which lasts through this year, featured 2 percent salary raises but also increased some out-of-pocket expenses on health care plans, Peck said.

“People are losing and then some from what they gained,” he said in an interview.

All the same, Peck said, union members were doing comparatively better in terms of cost-of-living raises than nonunion college employees.

“We’re lucky as a union because we can at least negotiate a 2 percent raise, but nonunion staff are even worse off than we are,” he said.

Although staffers can qualify for merit-based raises of up to 4 percent, Peck said, he didn’t know of any raises greater than 1.5 percent, despite knowing, as he put it, some “quality employees.”

In terms of employee compensation, “they’re just moving the ball around,” he said of the college.

Heatherton, however, said that he didn’t want people to think of professors as “a greedy lot who sit back and demand the biggest package we can have.”

The psychology and brain sciences professor said he had heard of instances in which people had turned down higher offers — including from nonacademic employers — in favor of Dartmouth. “If we just wanted to get rich we would go into industry, but most faculty have a higher calling, as it were, in terms of education,” he said.

And Peck, for his part, said he didn’t begrudge the faculty members their raises, whenever they may come.

“It may be good reasoning — we wouldn’t be here if not for them,” he said. “The college has to have the best professors to get the best students to be the best school.”

Rob Wolfe can be reached at rwolfe@vnews.com or at 603-727-3242.

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’