How Corning Inc. Handled Contamination of N.Y. Neighborhood

| Published: 02-11-2017 11:46 PM |

Corning, N.Y.

Decades later, after raising children, moving away, and then returning to her neighborhood on the east side of Corning, a city of about 11,000 in western New York, McDougal still collects the pieces of scrap that residents refer to as “cullet.”

The larger pieces that, until recently, she pulled from her vegetable garden became paperweights. She avoided the smaller fragments, remembering what her father used to tell her about the glassworks that once dotted the city and the industrial chemicals they left behind.

McDougal gave up her vegetable garden about a year ago.

As tests revealed the presence of lead, arsenic and other byproducts of glass and ceramic manufacturing on property after property in the neighborhood, including hers, state environmental regulators repeatedly warned her against planting anything new.

She and other residents of the Houghton Plot, a small neighborhood located less than a mile from the corporate headquarters of Corning Inc., the glassware manufacturer that took the city’s name, now are grappling with the consequences of the industry that built their community.

The name of her neighborhood reflects Corning’s influence: The Houghton family, founders of the company, owned the plot when it was still an undeveloped piece of farmland. Workers dumped waste glass and ceramics there until the early 20th century, when they covered the area with topsoil and built houses.

As Corning Inc. now works to define the limits of the contamination and compensate those affected, residents such as McDougal are asking themselves when and under what circumstances they might sell their homes.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

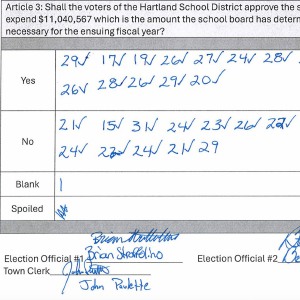

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

Hartland voters successfully petition for school budget revote

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

JAG Productions announces closure, citing ‘crisis facing the arts’

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

Hanover’s Perreard may soon capture the attention of collegiate coaches in two athletic pursuits

In McDougal’s case, the news of pollution also reminds her of the cancer that caused her husband’s early death, as well her daughter’s severe lupus — conditions whose causes she knows she can’t prove, but that do make her wonder.

“Does it have anything to do with the Houghton Plot?” she asked. “I don’t know, but I’m not having a vegetable garden anymore.”

Since last spring, Corning Inc. has been working to calm the market in the affected neighborhood by offering homeowners reimbursements for markdowns on sales of their properties.

The 10-month-old “value assurance program,” as these real-estate measures are commonly known, closely resembles an initiative that Dartmouth College launched last week to compensate Hanover residents for potential property losses from pollution at a former dump site for laboratory animals.

Under the new Dartmouth program, people living around Rennie Farm, a decades-old cache of carcasses near Hanover Center that leaked a stream of waste into the countryside, may ask the college to defray their real-estate losses.

The payments are scheduled to be available until 2022, when Dartmouth expects a treatment system to have cleared away the contamination.

The Corning Example

Dartmouth officials this month said they had modeled their program, in part, on Corning’s. The same consultant, global professional services firm Alvarez & Marsal, designed the two programs, and the booklets outlining the initiatives are nearly identical, in some places down to the typography.

Both programs offer to make up the difference when residents sell their homes below market value as a result of contamination, provided that the homeowners follow a process of listing and evaluation closely monitored by Corning or Dartmouth.

“As you would expect, these situations frequently have similar components, and practices for successful outcomes,” Ellen Arnold, a Dartmouth attorney who serves as the school’s director of real estate, said in an email.

“Dartmouth wanted to be generous in its approach and also propose a program with specificity. We thought the Corning model was a good example.”

Arnold also noted that value assurance programs have been used in many other places, and that despite the similarities, institutions offering compensation to landowners will adjust their programs to circumstances.

Dartmouth, for instance, says it will buy outright the homes of people who are unable to sell them. Corning is making no such offer.

Dartmouth also appears to be keeping the program’s management closer to home. The college brought in alumnus attorney Tom Csatari, a former Colby-Sawyer College trustee who works at Downs Rachlin Martin, to help run the initiative; Corning is farming out the work to Alvarez & Marsal.

And whereas the Corning contamination has already affected several homes in the closely packed neighborhood, only two families in the rural Hanover area near Rennie Farm have found the pollutant, a chemical solvent component called 1,4-dioxane, in their well. (Dartmouth denies responsibility for the second family’s contaminated well.)

Yet, as a homeowner weighing her options in light of market trouble caused by pollution, Margaret McDougal expressed many of the same concerns as Hanover residents did when presented with Dartmouth’s program last week.

Chief among them was the timeframe. Both programs last for five years, which McDougal, who is 73, says is not enough time to decide where she will spend the later years of her life.

“This is the hard part,” she said. “If I’m not ready to sell in five years, if my property value tanks, I’m out of luck.”

“I’ve lived here eight years,” she added, referring to her latest house, on Pershing Street, “and I feel like I just moved here. My friends are here and my family is here. I’m just not ready to go yet.”

Mixed Reviews

Less than a year into the program, real estate professionals familiar with the area haven’t yet reached a consensus as to whether it has succeeded in calming the market and making residents whole.

David Moses, a real estate agent who has worked extensively in the Houghton Plot, has mixed feelings about how the market-boosting effort has gone so far.

On the one hand, sales have recovered somewhat after the program’s institution, he said in an interview last week.

The neighborhood once had been considered desirable, thanks to its setting: a quiet grid of residential streets, near the center of town and the high school.

When news spread of the contamination, he said, no one would even look at a house in Houghton Plot.

“It kind of scared the daylights out of everybody,” he said. Now, he added, “things have picked up. Houses are selling.”

Yet Moses says his clients have not received what he would consider fair compensation from Corning Inc., and he says he worries what will happen to people who discover new contamination on properties after they buy them.

The value assurance programs in both Corning and Hanover exclude new buyers, and in receiving money from the programs, sellers agree to waive their rights to sue over property losses related to the contamination.

“I appreciate the fact that they’re trying to do something,” Moses said of the company, “but I don’t think the end result is that favorable to the homeowner. I don’t think that they’re getting fair market value, and the fact that it ends all liability on Corning’s end is a scary thought. Who knows what kind of contamination there is and how far down it goes and what the effect could be on people?”

Moses has sold seven or eight homes in the neighborhood recently, with another now under contract, and not all have changed hands below market value.

But in one case, he said, a property that was listed at what he felt was its fair price — about $165,000 — ended up selling for $135,000.

Hoping to make up the difference, Moses and the seller submitted paperwork to the value assurance program, and a Corning-approved appraiser came by and assessed the house — at $135,000.

The seller received little to no compensation, Moses said, although the program did reimburse the homeowner for Moses’s roughly $8,000 commission.

Moses said another of his clients had followed the value assurance process, commissioning soil tests and obtaining Corning-approved appraisals, but had been unable to persuade a buyer to sign a document that gives the company right of first refusal on the property.

Corning refused to compensate the homeowner, Moses said, citing the release that the purchaser wouldn’t sign.

A spokesman for Corning Inc. said he was unable to comment on the specifics of given cases because the company has delegated operational duties to Alvarez & Marsal.

Messages left for the program managers at the consulting firm were not returned last week.

The spokesman, Dan Collins, said Corning Inc. had given residents ample notice of the program’s requirements, including during meetings to announce the program’s rollout last spring.

“It was very clear,” Collins said in a telephone interview last week. “We went through a series of public meetings. We shared the information. Once the program went into the effect, we’re bound by the requirements of the program.”

Nevertheless, Moses said, he didn’t see why Corning couldn’t have relaxed the rules for his seller.

“They’re the ones that contaminated the soil,” he said, “so I would think they’d give people a little bit of leeway.”

A multibillion-dollar, publicly traded company, Corning Inc. employs tens of thousands and is a component of the S&P 500. The company maintains its headquarters in Corning, but has shifted most of its industrial work elsewhere.

Dartmouth, for its part, also asks that residents give the college right of first refusal.

The measure, which requires that homeowners who receive an offer on their houses give Dartmouth the chance to review and possibly take that deal, allows the college to verify that the offer is legitimate, school administrators said.

In last week’s interview, Collins, the Corning spokesman, said he couldn’t provide figures on what the company has paid out so far. Those numbers are in the hands of A&M, he said.

Collins also appeared to deflect responsibility on Corning’s part for the full extent of the Houghton Plot contamination.

He noted that the company’s participation in the real estate program had been voluntary and that state environmental regulators had not yet reached a formal conclusion as to the cause of the contamination and what remediation is necessary.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation “came and asked us if we would participate because there was potential concern about the soils, and we did,” Collins said. “But there is yet to be evidence that Corning is responsible.”

Frank Muccini, a city councilman who lives in the Houghton Plot, said pressure on the company to compensate landowners had begun with a school renovation and gained strength as spreading discoveries of contamination forced the buyouts of residential homes and delays in a hotel project.

As workers several years ago knocked down an old elementary school that stood to the south of the neighborhood, they found contaminants in the soil. That spurred rounds of tests in the area, eventually leading to the determination that toxic substances were spread all over the neighborhood, Muccini said.

Contractors came by Muccini’s property, on the north side of the neighborhood, and took samples.

They found 20 times the allowable amount of arsenic, he said, as well as lead, barium, cadmium, “and a whole bunch of other things.”

Meanwhile, the construction of a hotel nearby was pushed back when the developers discovered contamination on the lot, and anxiety rippled through the market as residents absorbed the extent of the problem through public meetings and local news reports.

When word spread, in summer 2015, that Corning Inc. was buying five private homes near the elementary school site, neighbors asked why they weren’t receiving offers, Muccini said.

Corning announced its real estate program in May 2016, and outlined the plan to the public during a series of public meetings.

Since then, Muccini said, it’s been all quiet, at least in terms of updating the public.

“They haven’t done anything,” he said.

The two state environmental officials who pushed for the program have since been reassigned, Muccini said, and regulators have not yet reached a conclusion about what kind of remediation is needed — nor, as far as Muccini could tell, have they returned to the neighborhood for additional tests.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation official now responsible for Corning did not respond to multiple requests for comment last week.

‘High Marks’ From Some Residents

Local officials more removed from the Houghton Plot offered a sunnier perspective on the value assurance program.

Corning Mayor Rich Negri said that the city’s namesake manufacturer had “taken the lead” in accepting responsibility for the cullet and other waste dumped years ago, as well as in making a “very generous” offer to compensate homeowners.

“From my distant observation,” Negri said, “the program seems to be not only working but getting high marks from the residents in that area.”

Theresa “Terrie” Burke, president of the board of the area association of Realtors, said that with or without the program the Houghton Plot remained an attractive neighborhood.

“With Corning offering the value assurance program, it’s been a benefit, but it really hasn’t changed the values of the property anyway,” Burke said.

“It’s still a good neighborhood. People still want to live there. Houses are not necessarily lingering on the market at all because of the soil issues. But Corning has decided they’ll give this added benefit so that people feel very safe about living in the neighborhood.”

Burke said she had sold one house there of late, and had another listed now. In terms of contamination, the property she found a buyer for was “one of the worst,” she said, “and it sold rather quickly.”

Alvarez & Marsal, the consultants handling the program, have been responsive, she said.

“It’s been pretty easy for us,” Burke said. “I’ve not heard of anybody having any difficulties at all.”

As for the man who lost out on compensation due to his buyer’s failure to sign away right of first refusal, Burke echoed the point that Collins, the Corning spokesman, had made about adhering to the rules of the program.

“Corning’s not in the real estate business,” she said. “They don’t want these houses. They’re doing that just to protect the value.”

Moses, however, said he couldn’t think of a single client, among the handful he has represented these past months, who had used the program and been satisfied with it.

McDougal, for her part, said the verdict among residents had been negative so far, and alluded to the tale of Moses’s right-of-refusal client, a story that appears to have made the rounds in the neighborhood.

The Department of Environmental Conservation has visited McDougal’s property for tests at least twice, she said, and found arsenic there at many times the allowable standard.

Given the high levels of contamination and the wide area that it occupies, she expressed doubt that Corning, with its compensation program, would be able to address fully the harm it may cause over time.

“Is their coming in and throwing money at it going to help things?” she said. “I don’t think so.”

Rob Wolfe can be reached at rwolfe@vnews.com or at 603-727-3242.

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’ Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination

Lawsuit accuses Norwich University, former president of creating hostile environment, sex-based discrimination In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary

In divided decision, Senate committee votes to recommend Zoie Saunders as education secretary