Column: Robert Frost connects the local to the global

| Published: 03-22-2024 3:10 PM |

Last June in a White House meeting, President Joe Biden gave India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi an extraordinary gift, an autographed first edition copy of the “Collected Poems of Robert Frost,” one of America’s greatest poets.

Modi responded with an equally unique gift, the “Ten Principal Upanishads” by Purohit Swami and William Butler Yeats, the renowned Irish poet whom Biden occasionally refers to and quotes in his speeches.

In India, however, the gift of Frost’s work was seen as a tribute to Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, who was deeply inspired by the poet. Nehru, apart from being a humanist, great statesman and founding father of Indian democracy, was a prodigious writer with a deep sense of history. He loved poetry and nature, and invariably spent his vacations in the awesome beauty of the Himalayan mountains, horseback riding and exploring woods. No wonder he found a kindred soul in Frost, whose meditations on life, nature and human limitations offered profound insights to Nehru.

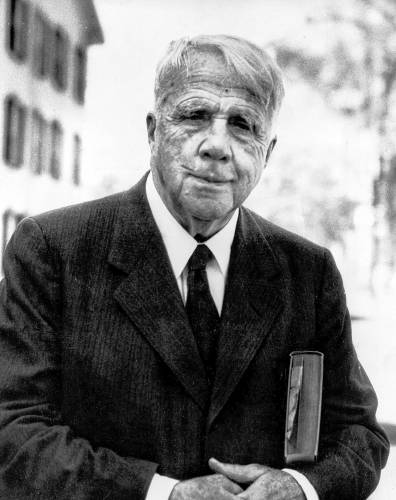

In the Upper Valley, Frost is linked to Dartmouth College, where he taught from 1943 to 1949 and was a regular presence on campus until 1962, the year before his death. The 150th anniversary of Frost’s birth is next week. Born in San Francisco on March 26, 1874, Frost came east with his family after the death of his father. He enrolled at Dartmouth, but stayed only a couple of months. His poetry is rooted in New England, particularly in New Hampshire and Vermont.

Dartmouth College will host a celebration of Frost’s birth starting at 3 p.m. on Monday in the East Reading Room of the college’s Baker Library. At 4 p.m. Tuesday, Prof. Tyler Hoffman, a Dartmouth graduate and Frost scholar, will give a talk titled “Robert Frost’s America” in the Wren Room of Dartmouth’s Sanborn House. Middlebury College, where Frost also taught, will hold a celebration on March 29.

Poet, novelist and Frost biographer Jay Parini said of Frost that, “He cuts across the class system in America and he speaks to both the ordinary man and woman and he speaks to the literary critic, the philosopher, the intellectual because he contains all of this in his work.” Indeed, Frost’s poetry transcends time and space and has what the English romantic poet William Wordsworth called “intimations of immortality.”

Nehru had a particular fondness for “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” which according to anecdotes from his friends and close associates, held deep meanings for him. Toward the end of his life, Nehru, troubled by health issues and the aftermath of the brutal China-Indian War (1962), kept a copy of Frost’s poems by his bedside, with the last stanza of “Stopping by Woods” heavily underlined:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

Herd departs Hartford’s last remaining dairy farm

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

At Dartmouth, hundreds protest ongoing war in Gaza and express support for academic freedom

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Claremont removes former police officer accused of threats from city committees

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

Over Easy: ‘A breakfast without a newspaper is a horse without a saddle’

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

The poem reflected Nehru’s sense of duty to his young nation and the journey still ahead.

The connection between Nehru and Frost’s poetry was more private and symbolic, with Nehru finding solace and inspiration in Frost’s verses on a personal level. This influence likely affected Nehru’s approach to leadership in a more subtle and introspective manner rather than being explicitly articulated in his political speeches.

There’s another reason why Frost’s poems chime with Indian sensibilities. Frost’s poetry and India’s Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry share similarities in their connection to nature and the emotions they evoke. Both poets, despite coming from different cultures and civilizations, vividly envision nature as a source of inspiration and reflection. Tagore perceives nature as a nurturing mother that needs to be respected and preserved, emphasizing the importance of harmony between humanity and the natural world. Similarly, Frost’s poetry often reflects a deep appreciation for nature’s beauty and the need to coexist with it reverentially.

While Frost and Tagore express their reverence for nature in distinct ways, their shared themes of nature’s beauty, its influence on human emotions and the necessity of preserving it resonate across their works. Both poets depict natural imagery such as flowers, rivers, morning and evening scenes, stars, and more in intricate detail, creating a deep emotional connection between nature and humanity. Frost’s poetry aligns with Tagore’s in its portrayal of nature as a source of wonder, beauty and spiritual significance. Both poets convey an overwhelming awe of nature’s magnificence.

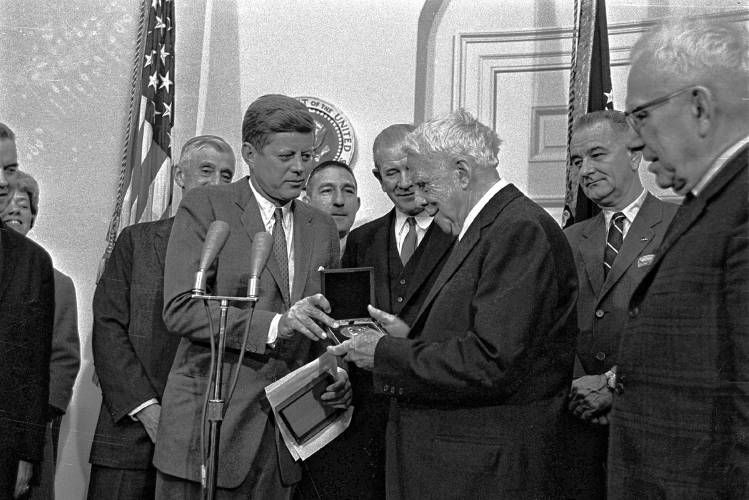

But poetry may have another function. Frost recited “The Gift Outright” at President Kennedy’s inauguration. In one of his final speeches, at the dedication of the Robert Frost Library, at Amherst College, in October 1963, Kennedy said about the poet, “He has bequeathed his nation a body of imperishable verse from which Americans will forever gain joy and understanding. He saw poetry as the means of saving power from itself. When power leads man toward arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

Nonetheless, Frost does not arrogate to himself the tall claim that his poems offer the ultimate truth or solution to life’s problems. As he says in his preface to his collected poems, that “The Figure A Poem Makes,” … “begins in delight and ends in wisdom ... in a clarification of life — not necessarily a great clarification, such as sects and cults are founded on, but in a momentary stay against confusion.”

“A momentary stay against confusion,” as literary critic Donald Pease, the Geisel Professor of Humanities at Dartmouth College, explains in one of his lectures, means that Frost’s poetry exists in order to produce in the act of reading the poem the capacity within the reader to share the sudden moment of clarity that emerges from the poem. The reader is transformed by sharing the poet’s experience.

That’s the joy of reading poetry. It enlightens the reader, whether he is in America or in India, pondering how his karma might have changed if he had followed “The Road Not Taken.”

Narain Batra is the author of several books including the most recent “India In A New Key: Nehru To Modi.” He lives in Hartford.

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives

Editorial: Parker parole a reminder of how violence reshapes our lives Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum

Editorial: Chris Sununu’s moral vacuum Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life

Editorial: Gambling tarnishes America’s sporting life By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths

By the Way: A white nationalist’s many mistruths