Andy Harvard, Part One: A Mountaineer Laid Low

| Published: 06-09-2016 4:18 PM |

I’m fairly certain Andy Harvard’s story is one that Dartmouth College doesn’t want told. But it needs to be. The secrecy has gone on far too long.

Seven years, and counting.

So let’s begin.

—

In the early 2000s, with its 100th anniversary approaching, the Dartmouth Outing Club was treading water.

Many of the DOC’s 20 wilderness cabins were in shambles from years of neglect. Two directors of outdoor programs — the college administrator who oversees the DOC — had come and gone in less than four years.

And, perhaps most disheartening of all, there was a growing belief that students entering Dartmouth didn’t possess the same zest for outdoor pursuits as their Big Green ancestors. They seemed more interested in learning to climb the corporate ladder than the White Mountains.

In need of a game-changer, Dartmouth turned to Andy Harvard.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

Zantop daughter: ‘I wish James' family the best and hope that they are able to heal’

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

James Parker granted parole for his role in Dartmouth professors’ stabbing deaths

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

2024 Upper Valley high school softball guide

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Art Notes: After losing primary venues, JAG Productions persists

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

Chelsea Green to be sold to international publishing behemoth

With four Mount Everest expeditions to his credit, Harvard was a household name in the mountaineering community. When he wasn’t scaling the world’s highest peaks, he worked as a corporate lawyer. And he was a Dartmouth graduate.

“The hiring of Andy Harvard ’71 as director of outdoor programs in 2004 appeared like a lifeline,” the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine would write years later . “Harvard, a world-class mountaineer with extensive legal and on-the-ground experience in outdoor risk and risk management, seemed unusually well positioned for the times and — except for his last name — a good fit for Dartmouth.”

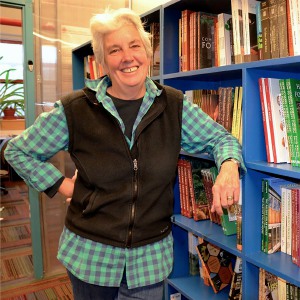

In the summer of 2004, Harvard filled his new corner office with mountaineering gear, photos of his expeditions and books on the outdoors.

“I moved all my stuff in quickly,” he told the alumni magazine shortly after his arrival, “because I wanted everyone to know that I intend to be around for a long time.”

Then on a Monday in early July 2008 — slightly more than four years after his hiring — Harvard was in his office when Joe Cassidy, the college’s acting dean of student life, stopped by.

It wasn’t a social call.

Cassidy informed Harvard that he had until Friday to empty his office in Robinson Hall. Harvard was handed a statement that the college planned to email to the Dartmouth community. The college’s official line would be that Harvard had decided to step down. Dartmouth wanted people to think that Harvard’s abrupt departure was his doing.

What choice did he have other than to go along?

He was a few weeks shy of his 59th birthday. He and his wife, Kathy, had three young children and had just built their dream house on the Connecticut River in Hanover.

Any chance of Harvard receiving a decent severance package from the college hinged on his silence.

“We were terrified about what Dartmouth could do to our family,” Kathy Harvard told me recently. “It was made clear to Andy that if he went public, he’d end up with nothing.”

For seven years since then, the Harvards stayed quiet about the firing and what transpired subsequently. Over the years, the Harvards’ attorney, Geoffrey Vitt, of Norwich, and the college have held on-again, off-again talks about a financial settlement.

But the two sides could never agree.

Dartmouth alumni, people with DOC ties and friends of Andy Harvard have tried to intervene, taking up his cause with three Dartmouth presidents during the last seven years.

Nothing worked.

A few weeks ago, the Harvards and Vitt gave me access to letters, some of them written by an in-house Dartmouth attorney, that shed light on what has taken place. Much of this two-part series is based on that correspondence.

Other people with first-hand knowledge of the matter turned over letters and emails — some of which have made it to 207 Parkhurst Hall, the office of Dartmouth’s president — that provide important details.

Although Phil Hanlon didn’t arrive in Hanover until 2013, I’m pretty sure Dartmouth’s current president has known for a while what’s been going on.

I wanted to talk with Hanlon, but his office wouldn’t make him available. Kevin O’Leary, Dartmouth’s associate general counsel who has served as the college’s point man in the Harvard case, also declined to be interviewed.

—

Dartmouth is famous for students and alums who “bleed Green.”

Harvard, the son of a stay-at-home mom and a surgeon who taught at Yale Medical School, was fairly typical in that regard.

He didn’t have to think twice about following his older brother, Stephen, to Hanover. The Connecticut River and nearby mountains that Dartmouth offered were too much for an Eagle Scout to resist.

“I walked in, and that was me,” he said.

As a freshman, he joined the Mountaineering Club. In 1970, his junior year, he was among a small group of Dartmouth climbers who traveled to Bolivia to scale 20,892-foot Illampu and 19,974-foot Huayna Potosi.

After graduating in 1971, Harvard put off law school. He had mountains to climb and rivers to explore. Along the way he met Kathy, who traveled in the same mountaineering circles.

By 1979, Harvard had his law degree from Boston University, a good chunk paid for by money he saved up while working on the oil pipeline in Alaska.

He began his law career as an assistant attorney general in the state of Washington, followed by a litigator’s position with the Federal Reserve Bank in New York.

Harvard didn’t spend all his time in a suit and tie.

In the fall of 1980, an American mountaineering group asked him to make a reconnaissance trip to the East Face of Mount Everest.

The East Face hadn’t been climbed since 1921. After British climber George Mallory made history, mountaineers wisely opted for more accessible routes up the world’s highest peak.

With a pair of Tibetan yak herders serving as guides, Harvard and two Chinese companions spent days trekking through altitudes as high as 17,000 feet. When his climbing partners had said they’d seen enough, Harvard hiked on alone.

Two days later, he reached the foot of the East Face. For the next couple of days, he mapped out a route up a 6,300-foot rock wall to the summit of Mount Everest.

In 1981, an American climbing team used Harvard’s map to scale the rock wall but failed to reach the summit. In 1983, seven members of the team returned to conquer the East Face of Everest — the first time in more than 60 years.

Harvard was part of both expeditions.

He wrote about his mapping of the “sheer wall once regarded as unscalable by mountain climbers” for the July 1984 issue of National Geographic.

—

By the mid-1980s, Andy and Kathy had settled in Fort Wayne, Ind., where he served as general counsel for a European agribusiness conglomerate for the next 15 years.

They remained connected to the Upper Valley, buying a small house in Hanover with access to the Connecticut that they used for vacations.

With James, their oldest, in elementary school and 4-year-old twins, Nick and Allegra, the couple started giving serious thought to moving permanently to Hanover.

When Andy heard that Dartmouth was searching for a director of outdoor programs — its third search in four years — in 2004, he didn’t hesitate. Neither did Kathy.

“This was our real home, not Indiana,” she said. “Part of our unwritten game plan had always been to get back here.”

The DOC was considered the oldest and largest collegiate outdoor club in the country. Giving students the chance to hike, canoe and ski out their back door, the DOC helped Dartmouth stand apart from its Ivy League brethren.

But rock climbing, mountaineering and whitewater kayaking can be risky, which tends to make lawyers assigned to protecting Dartmouth’s financial interests nervous.

Harvard believed that some risks were worth taking. By taking advantage of their wilderness surroundings, Dartmouth students could learn lessons that would benefit them later in life, even on Wall Street.

“In real time, on a mountain that’s cold and hard, on a wild river, you get moments of clarity and certainty that you can’t get in any classroom,” Harvard told the alumni magazine.

He felt strongly that the DOC should get back to its roots. That meant keeping the DOC a student-run organization — just as it had started out in 1909, but had drifted away from in recent years.

Harris Cabin, the DOC’s 49-bed lodge off the Appalachian Trail on Moose Mountain in Hanover, was Harvard’s litmus test. A prized DOC asset, only 9 miles from campus, Harris Cabin was literally falling down.

Did Dartmouth students care enough to rebuild the lodge?

Harvard got his answer soon enough.

Students cut logs for the walls and hauled rocks to rebuild the fireplace chimney. Before heading into the office in the morning, Harvard hoofed it to the cabin to check on their progress.

“He was our strongest advocate,” said Chris Polashenski, a student who had arrived in Hanover a year ahead of Harvard. “He put us in circumstances that taught us to deal with risk and uncertainty.”

Not all projects that students undertook during Harvard’s tenure were as successful as Harris Cabin, which has since been renamed the Class of 1966 Lodge. “He was supportive, but he also wasn’t afraid to let students learn by failing,” said Polashenski.

Harvard hadn’t worked in academia. He preferred cutting wilderness trails with students to sitting in meetings with other administrators. He was good at raising money ($500,000 in four years, according to one estimate that I’ve seen), but he lacked patience with the slow pace with which Dartmouth administrators tackled problems.

“He probably came on like gangbusters. That was his style,” said Kathy. “Could he have stepped on toes? You bet.”

I contacted Cassidy, Dartmouth’s acting dean of student life who delivered the news to Harvard in the summer of 2008 that he was being fired. Cassidy told me that it wasn’t their first frank conversation.

“I worked with Andy Harvard on a number of performance-related issues for an extended period of time,” emailed Cassidy, who is now an administrator at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y.

In early 2008, Dartmouth brought in a three-person “external review” committee to examine its outdoor programs. Looking back, some DOC people I talked with think it was a smokescreen. They thought Dartmouth administrators wanted the committee, consisting of educators with backgrounds in outdoor clubs, to serve as the hired gun needed to sack Harvard.

He provided them with some ammunition.

Harvard had started to miss deadlines for submitting department budgets and annual reports. He didn’t always respond to emails from his superiors. He was criticized for not “speaking more quickly and getting to the point,” said Kathy, who didn’t know what to make of the bits and pieces her husband was telling her about his difficulties at work.

She chalked up some of it to changing times. “He wasn’t technology savvy,” she said. “He didn’t live on his computer. But he had always been well organized and good at planning logistics. This was a guy who could figure out how to get six tons of (mountaineering) equipment that needed to be packed and shipped to a remote part of the world.”

Her husband was still putting in the effort. He worked nights and weekends. Any struggles with carrying out his day-to-day DOC duties, “I attributed to being overworked and stressed,” said Kathy.

The external review committee raised a serious concern. There was speculation that Harvard might have a drinking problem.

In the spring of 2008, the committee gave a draft of its report to Dartmouth officials. The committee said it still had more work to do, but the college didn’t want to wait.

Shortly thereafter, Harvard was gone.

People familiar with the DOC immediately questioned whether Harvard had actually stepped down as the college claimed.

Polashenski, who at the time was studying at Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering, sent an email to DOC members that later appeared on DartBlog, alum Joe Asch’s popular online site.

Harvard envisioned a “club in which students not only led trips, but also choose, train and approve their peers to lead future trips, under criteria that they, not lawyers write,” wrote Polashenski. “In his drive to push things forward, Andy rubbed some people the wrong way … or didn’t play politics right.”

Two weeks after Harvard’s departure, 40 students and alums signed a letter addressed to the “Dartmouth Community.” It didn’t mention Harvard by name, but it didn’t need to.

“Three short-lived (outdoor program directors) in eight years, combined with the administration’s silence about our future, leave us worried that there is a fundamental misunderstanding between the administration and the Dartmouth Outing Club.”

At the urging of Harvard’s supporters, then-President James Wright agreed to review the matter. Wright stood by his subordinates’ decision to fire Harvard. (I recently emailed Wright, but was told by his assistant that he probably wouldn’t get back to me because he rarely comments on personnel matters.)

Samuel Silverstein, a 1958 graduate and physician, contacted Wright in October 2008. “Whatever the reason for his dismissal, the manner in which it was carried out was extremely prejudicial to his ability to obtain future employment,” wrote Silverstein. “All of this has had a devastating effect on him personally, and on his family.”

Meanwhile, Andy and Kathy had contacted Vitt, who was experienced in representing current and former employees in their employment dealings with the college.

In the late summer and fall of 2008, Vitt and O’Leary, the college’s associate general counsel, discussed a severance package that would provide Harvard with his $96,000 annual salary and benefits through June 30, 2009.

After he was fired, Harvard began seeing Dartmouth-Hitchcock psychiatrist Matthew Friedman, who diagnosed and treated him for depression.

Harvard also seemed to be having problems with his speech and memory. At an informal gathering of DOC students that Harvard attended after his firing, people wondered if he’d been drinking.

“He was always a careful, methodical speaker, but he was struggling to find his words,” recalled Polashenski, “You could see the frustration in his face. It wasn’t that he was trying to be elegant. He couldn’t find the words.”

Nine months after his dismissal, Harvard and the college still hadn’t agreed on a severance package. Dartmouth continued to provide health insurance to Harvard and his family.

He’d need it.

Friedman wasn’t convinced that depression was all that ailed his patient. Starting in April 2009, Harvard underwent a battery of neuropsychological tests, including MRI and PET brain scans.

Kathy talked with her husband’s doctors. She explained that, as a world-class mountain climber, he’d spent a lot of time over the years at high altitudes where oxygen was in short supply.

“Could it have done something to cause damage to his brain?” she asked.

—

Jim Kenyon can be reached at jkenyon@vnews.com.

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool

Some families find freedom with Newport microschool Woodstock Aqueduct Company seeks to double water rates

Woodstock Aqueduct Company seeks to double water rates