A Life: Royal Houghton ‘was never one who did things half way’

|

Published: 01-28-2024 8:15 PM

Modified: 01-30-2024 10:38 AM |

ASCUTNEY — Royal Houghton struggled in elementary school, left high school after his junior year to join the Navy as World War II was winding down and he never earned a degree.

Still his artistic talents, engineering aptitude, volunteer work and cycling milestones added up in his long life of 96 years. The early adversity makes his accomplishments all the more remarkable.

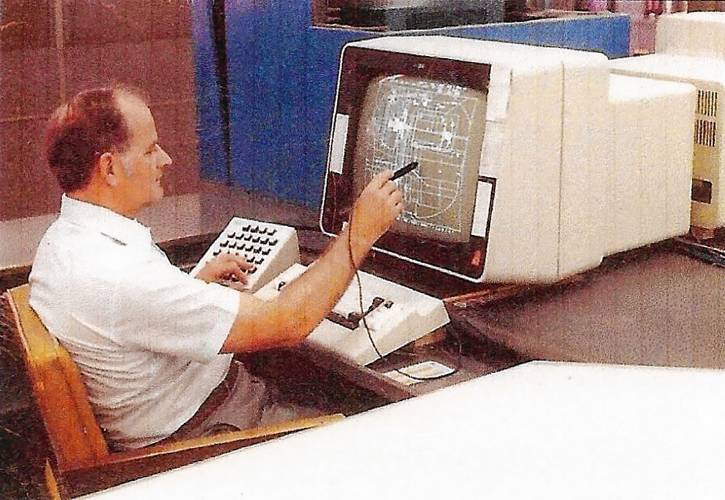

Houghton, who died in October, worked for nearly 40 years in the machine tool industry, from its height in the 1950s to its slow decline as a major line of business in the region in the late 1980s. He rose to the position of draftsman and engineer, working on machine design for Cone Machine in Windsor, Joy Manufacturing in Claremont and Bryant Grinder in Springfield, Vt.

Houghton’s is among the names listed on two patents issued in 1975 and 1985 for inventions he helped design as a machine engineer while employed at Bryant Grinder.

"He was so humble about it," his granddaughter, Cecelia Tarr, of Portsmouth, N.H., said about Houghton's engineering aptitude. "It is incredible he was able to do all that without even a high school diploma." A Veteran's Day program to award Houghton a diploma took place last year but the diploma was awarded posthumously.

Houghton never considered himself smart or a good student, his daughter, Patti Arrison, said. Still he could do math in his head and had an engineering mind, despite no formal schooling in the discipline.

"I think he was truly (an) autodidact; he taught himself how to do things," she said.

She recalled their shared struggles with her algebra homework: "I think he had the kind of mind that could leap from the problem to the solution, whereas I needed to see each and every step in a painfully slow progression."

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Three vie for two Hanover Selectboard seats

Three vie for two Hanover Selectboard seats

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

Norwich author and educator sees schools as a reflection of communities

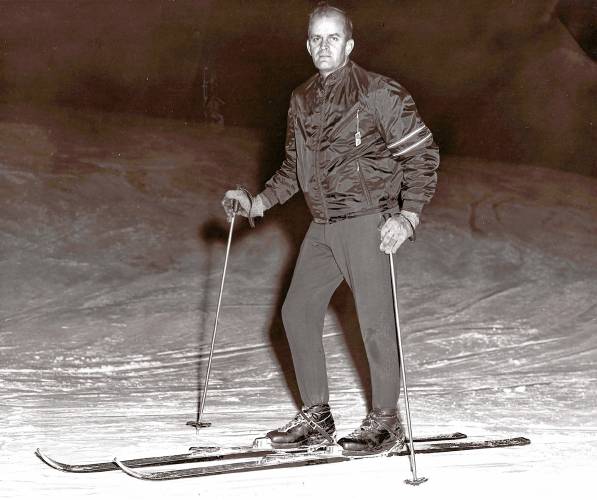

Houghton began life in Bridgewater Corners, frequently roaming the woods, learning to hunt, fish and ski on the steep slope behind his house. He worked summers at area farms, helped with sugaring in the spring and joined his father after school at the Bridgewater Woolen Mill where the senior Houghton was head of the maintenance department.

"He grew up in the Depression but I remember him saying he didn't remember being in want of anything," said John Arrison, Houghton’s son-in-law.

Houghton's father worked at the Calvin Coolidge estate in Plymouth, Vt.

"Uncle Royal would talk about Coolidge's wife driving to their home to visit him," his niece, Susan Holmes said.

With his mother's permission, Houghton left school in April 1945 to join the Navy, a month before the Allies declared victory in Europe. Patti Arrison said her father was stationed at Pearl Harbor in the labor transportation division, working as a mechanic on the landing craft that moved ships docked in the harbor and ferried supplies out to the ships. After his honorable discharge in 1946, he returned to the woolen mill, where he was a mechanic, but was later laid off and went to work for Cone Machine in Windsor in 1950.

At Cone her father built machines on the factory floor and then got a break when he was offered the chance to take a drafting course, Arrison said.

"He liked to draw and something just clicked when he took that course," she said. "The course gave him the opportunity to embark on a new and highly satisfying career. He was largely self-taught from that point onwards, but he often acknowledged with gratitude the senior engineers who were willing to talk with him whenever he had a question."

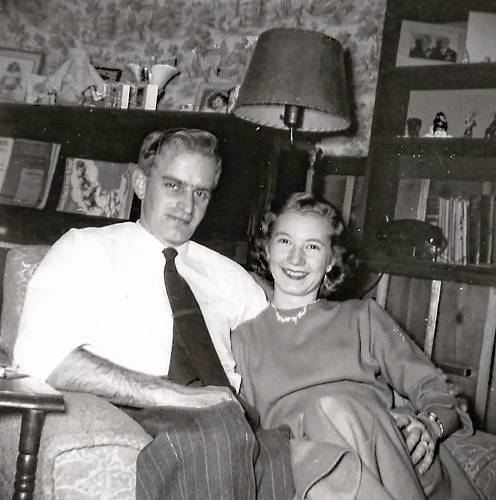

At Cone, where he worked for a dozen years before moving to Joy Manufacturing in Claremont, Houghton met his future wife, Marilyn Trask, who worked in the purchasing department at Cone. The couple married in 1955 and shared 68 years together until his death. They began married life in Bridgewater but soon moved to a new home in Ascutney, where they lived for 65 years.

Houghton was hired at Bryant in 1964, got laid off in 1970 and returned two years later after working as a tool engineer in Keene, N.H. At Bryant, where his patent work was done on Grinding Wheel Truing Mechanism, issued in 1975, and Gimbal-mounted Dressing Device, issued in 1985, Houghton was a project engineer.

"It has been a very satisfying life to design something on paper and then see it in steel, and I loved every minute of it," Houghton wrote in a memoir that he never published but shared with friends.

Ken Blum, of Ascutney, worked with Houghton for several years at Bryant and remembers his sketching skills.

"He was half artist, half mechanic," Blum said. "Not everybody could do that, put their thoughts down on paper so quickly in sketch form. He could go from a sketch form on paper to a full-drafted part or machine."

Ever the tinkerer — like most engineering minds — Houghton would welcome the chance to build or design something. "He built furniture and could fix just about anything," said his daughter.

Tarr said her grandfather "was so good at problem solving and so good at working with his hands and understanding how things worked."

His incredible artistic talent as a painter, photographer and wood carver are some of her fondest memories.

"What really sticks out for me is he carved 3D images out of wood. The back would be flat and mounted on something," Tarr said. "He carved a skier, horses and him on a bike. They were unique and captured all the things he was passionate about."

Warned by a doctor to take up some exercise, Houghton was in his mid 40s in the 1970s when he pulled his daughter's 10-speed bike out of the garage and began riding, with a 25-mile loop around Mt. Ascutney, a regular route. Close to 40 years and several bikes later, Houghton exceeded 100,000 miles.

"My father was never one who did things half way," Patti Arrison said about his passion for riding and meticulously recording his mileage.

Houghton retired in 1988, partly for reasons related to the finances of the company and his pension but for another reason as well, Patti Arrison said.

"He felt that he should step aside, so that a young man, an up-and-comer, could have the same kind of chances that he had enjoyed," she said. “That was the kind of man my dad was. Humble and self-effacing; he belittled his accomplishments and contributions."

Family members say Houghton was quiet and shy, with no interest in being recognized for his successes or the countless hours of volunteering for his town after retirement.

"He was very private and very shy," said Arrison's husband, John, a Democratic state representative from Weathersfield and a former Weathersfield Selectboard member.

One incident stands out for John Arrison that characterized his father-in-law's reluctance for the spotlight.

Houghton did a wood carving of the town seal, which today hangs in the town offices in Ascutney. John Arrison invited him to a Selectboard meeting to display the carving and publicly thank Houghton. His son-in-law got him to the meeting, but just barely.

"All he would do is peek around the corner," John Arrison remembered. "He would not come into the room."

Houghton spent much of his retirement helping his town.

"He never articulated this idea, but I believe he saw his volunteer contributions as ways to recognize and honor the people who had given him a step up when he was a young man," Patti Arrison said.

Houghton lent his talents on plans for the addition to the school in Ascutney and proposed town offices and also volunteered with other projects including the Weathersfield Center Meeting House.

"If there was a need he would quietly, without being solicited, offer some sketches and ideas," said John Arrison. "He did not announce he could do something, just sketched something and asked people what they thought. He liked to use his drafting skills on behalf of the townspeople."

Patti Arrison said at times, her father would be asked to draw up plans for proposed building, which he willingly obliged, while other times he "volunteered simply because he wanted something to do," such as glazing the roughly 100 window panes on the Weathersfield Center Meeting House.

"He did not like to have nothing to do," she said. "Up until this summer he was still driving his car, mowing his lawn, fixing things around the house, and taking care of my mother.

"About 25 years ago, he put in countless hours working on the construction of the new fire department building, (in Ascutney) helping with hands-on jobs like plumbing." his daughter said. "Retired from full-time work, he said he wanted to make up for the years he had not been able to volunteer because he was too busy."

"My dad strongly believed that it is important to give as much — or better yet, more — than you have received," Patti Arrison said.

Patrick O'Grady can be reached at pogclmt@gmail.com.

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community