A Life: George Lawrence sought out an artist’s existence

| Published: 10-23-2023 4:47 AM |

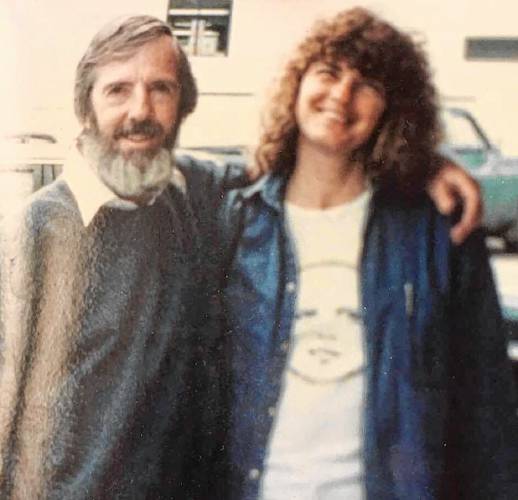

TUNBRIDGE — Artist and musician George Lawrence seemed almost effortlessly creative during his long life, but some examples stand out.

One year, the Terami family, his neighbors on Ordway Road in Tunbridge, had some volunteer gourds grow up around their compost pile. They were pretty, so as a gift, the Teramis placed a selection of them on the woodpile at the home Lawrence shared with his wife Jacquelyn JiMoi. Lawrence was taken with the scene.

“He painted that in watercolors and gave it to us as a gift,” Kathi Terami said in a phone interview.

This typified how Lawrence made use of his talents. He made art and music, he made a living and he made friends. He and JiMoi came to Vermont to devote themselves to their creative lives, and for over 40 years, that’s what they’ve done.

Lawrence died on Sept. 20 of bone cancer. He was 89 years old.

In the Upper Valley, where he’d lived since 1980, Lawrence was best known as a realist painter, mainly in watercolor, and as a member of the long-standing musical act Jeanne and the Hi-Tops.

The foundation for his creativity was built in childhood. He liked to draw from an early age, JiMoi said in a phone interview, and his mother encouraged him. At church, she’d give him pencil and paper to keep him occupied.

Lawrence was born in Florida, but his family moved to Ohio when he was quite young, so his father could work assisting the war effort. They lived in a Quonset hut, and George spent a lot of time hunting and fishing. Money was tight enough that George’s father purchased ammunition by the cartridge, three at a time, rather than by the box, JiMoi said.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Dartmouth administration faces fierce criticism over protest arrests

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

Hanover house added to New Hampshire Register of Historic Places

Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school

Sharon voters turn back proposal to renovate school

During high school, Lawrence picked up a lap steel guitar and took some lessons. He and two friends formed a band and won a high school talent show. His high school classmates voted him “most likely to succeed as an artist.”

The art school Lawrence went to in Florida shut down, and he opted to enlist in the Army rather than wait to be drafted, a decision that meant he’d serve a shorter term. He resisted the military’s insistence on beating troops down and building them back up, JiMoi said. His Army years troubled him the rest of his life. He was part of a unit that scoured the German countryside for Nazi boobytraps and saw some of his fellow soldiers wounded in the process.

“Until he died, he had nightmares,” JiMoi said.

After the Army, the GI Bill paid for him to attend to Ringling School of Art, in Sarasota, Fla. He waited tables at a swank restaurant to pay for books and rent, and he worked as a sign painter for the circus. For a time, Lawrence lived a fairly conventional life, working as a creative director at an ad agency in Tampa, Fla. He was married to Nancy Lawrence for eight years, and adopted her son, Rodney. Their daughter, Romy Lawrence, lives in Kansas. An attempt to reach her via email was not successful.

When the marriage broke up, Lawrence took care of both children, JiMoi said.

Lawrence and JiMoi were introduced by a mutual friend. They were both on the rebound from failed marriages, but their attraction overcame their wariness.

“It was love pretty early on,” JiMoi said.

Before they met, JiMoi already had made plans to move to Vermont. She moved in 1978, but continued to court Lawrence for 17 months, talking him into moving north. He made the move in 1980.

Their intention was to live the creative life that lay hidden under their professional work, JiMoi said. Living in Tampa, Lawrence painted and played music at night. They wanted to devote their lives to creative work.

“We just knew we had to come up here to be who we wanted to be,” JiMoi said. She’d grown up on Key West and said Vermont is kind of like an island, remote and friendly and focused on community.

They lived for a year in South Woodstock, then in East Barnard, then in North Pomfret, before buying land for a house in Tunbridge. JiMoi worked in the library at Woodstock Elementary School, and Lawrence did freelance graphic design work, including for Woodstock’s Pentangle Council on the Arts.

JiMoi had always wanted a round house, but the construction would have been too costly, so they found a builder willing to erect an octagonal house. There are two such homes on Ordway Road, the first one built up the hill from Lawrence and JiMoi’s, the second one built for them.

The Teramis purchased the house up the hill and moved in in 1998. Lawrence had a studio in an outbuilding on the property. “We used to joke that he came with our house,” Kathi Terami said.

His creativity showed itself in the smallest interactions. He would hand-letter signs welcoming the Teramis home, or making parking signs for parties they threw. He had a big influence on the Terami children, Rose and River, with Lawrence and JiMoi acting almost as neighboring grandparents. Rose once gave Lawrence a lollipop, and he made her an elaborate thank you card, which she still has.

Lawrence also was a gifted raconteur, often telling stories in which was the subject of the humor. “I probably have more stories about George than about everybody else in my life,” Terami said.

On Ordway Road, Lawrence and JiMoi lived mostly without television and in the evenings, JiMoi would read aloud while Lawrence painted, often on matchbook covers. They gave candles as gifts and Lawrence decided to paint the matchbooks as accompaniment. He ended up making more than 1,000 of them, JiMoi said. They were painted loosely; Lawrence said he had to lift up his brush to see the result, since the paintings were so small.

This was in contrast to his more formal work, which was realistic and often finely detailed, rendered in either watercolor or acrylic. His most viewed work is likely the panorama of South Royalton village that he made as a commission from Royalton resident Thomas Powers. It hangs above the cash registers in the South Royalton Market, a food co-op in town.

Not all that long after moving to Vermont, Lawrence met Jeanne McCullough while shooting pool at a bar called Blazing Saddles on Route 107 between Bethel and Stockbridge. (It was later known as the Peavine Pub and is now closed.) At the time, McCullough was in her 20s and singing at open mic nights. Lawrence encouraged her.

“The first time we actually connected with music was at the South Royalton House,” she said. Dick McCormack, now a longtime state senator, was performing and he asked her if she’d like to play at the very first Bethel Forward Festival. Lawrence said he’d pull some other musicians together. McCullough, Lawrence and a core group of Terry Cantlin, David Indenbaum, Cannon Labrie, Jack Kruse and Michael Bradshaw, performed together for seven years as Jeanne and the Hi-Tops. They disbanded, but later reassembled for another seven years.

“He was very supportive of me, and pushed me,” McCullough said in a phone interview. “We were really a fabulous band.” They also were good friends, getting together for potlucks and rehearsals.

For the most part, Lawrence’s art and music consisted of local engagements. He was not interested in grasping for any kind of brass ring. He like to entertain and to be entertained, but didn’t expect or covet riches.

“It would have been fine with us if money had come our way, but not at the cost of how we wanted to live,” JiMoi said.

They made it work, volunteering at the South Royalton Market to earn a discount on groceries, refinancing their home every five years or so to cover costs of other necessities.

Late in life, Lawrence developed an “intention tremor,” which manifested itself as a shaking hand when he tried to perform a focused task, such as painting or his lap steel or dobro. The South Royalton panorama, completed in 2012, is his last major figurative work. He tried to make abstract paintings, but nothing he tried ever quite worked out, JiMoi said.

The loss of painting income led the couple to sell their Tunbridge home in 2017. They divided their time between the home of friends in the White River Valley and Okracoke Island, on North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

Even the loss of his artistic pursuits didn’t dim Lawrence’s creativity. He still told stories, and as his memory began to fade, not through Alzheimer’s or dementia but garden-variety old age, he learned to laugh at his own forgetfulness.

“He refused to let it change him,” she said. Just two days before he died, he sang one of the many songs he’d written for the nurses caring for him, creative to the last.

Alex Hanson can be reached at ahanson@vnews.com or 603-727-3207.

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together

Art Notes: Canaan Meetinghouse showcase brings musicians and listeners together A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times

A Look Back: Upper Valley dining scene changes with the times The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute

The future of fertilizer? Pee, says this Brattleboro institute From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community

From dirt patch to a gateway garden, a Randolph volunteer cultivates community